The Western Front 1916: The Battle for Verdun

The initial German invasion of France had been stopped at the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914. The attempt of each side to outflank the other ended at the Battle of the Yser and the First Battle of Ypres. As 1914 came to a close each side dug in behind an extensive system of trenches and field fortifications. A series of Allied offensives beginning with the Battle of Neuve Chapelle and including the Second Battle of Ypres, the Second Battle of Artois and finally the Second Battle of Champagne, failed to change the frontlines in any meaningful way.

During 1915, the Germans focused on achieving a decisive breakthrough on the Eastern Front in an attempt to knock Russia out of the war. The Russian advance in the Carpathians was initially successful, capturing the Austrian fortress of Przemysl and advancing deep into Galicia. The advance proved to be short-lived, however, as the German-Austrian led Gorlice-Tarnow offensive halted the Russian advance and then broke through the Russian lines precipitating a general Russian retreat from Poland and Galicia. By the end of the summer, German troops had occupied Warsaw and Vilnius and had crossed into Ukraine. Russian forces ended the year bloodied but still standing.

As 1916 dawned, unable to achieve any kind of decisive breakthrough on either the Western or Eastern Fronts, the German General Staff developed a new plan. The Chief-of-Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, insisted, in a purported Christmas Day letter to the Kaiser, that the way to victory in the war lay not in the east, against Russia, but in the west, against France. In order to starve Britain and force it out of the war, he argued, a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare (which he acknowledged ran the risk of drawing the United States into the war) should be conducted against merchant shipping. At the same time, a major set-piece victory against the French would either bring the Allies to the negotiating table or ensure their defeat. The Kaiser was persuaded by von Falkenhayn's reasoning, and thus set in train the events that led to the Battle of Verdun. It was a battle that would eventually cost von Falkenhayn his job and result in the deaths of some 700,000 German and Allied soldiers.

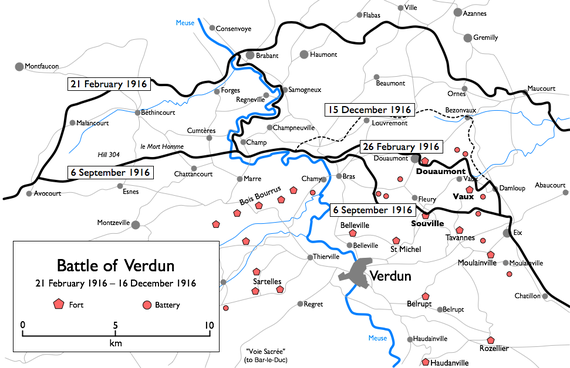

Verdun, on the banks of the River Meuse, held a special, symbolic place in the hearts of the French people. A role it retains to this day. A fortress since Roman times, it had been the last fortification to fall to the enemy in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71. Since then, it had become part of a defensive line running from Belfort through Epinal, Verdun and Toul across the Belfort gap. The gap, nicknamed the Burgundian gate, was a 30-mile wide zone between the Jura and Vosges mountains that had been the traditional invasion route from Germany into eastern France. Twenty forts garrisoned by 20,000 troops now protected Verdun, at the center of the Belfort gap.

Von Falkenhayn believed that that French Army would attempt to hold the east bank of the Meuse at all costs. Once defeated, they would commit their strategic reserve to recapture that terrain. The combination of precise and massive German artillery fire and well defended, entrenched German infantry would inflict catastrophic losses on the French. Falkenhayn's plan was simple and terrifying. Knowing that France would not allow Verdun to fall, he proposed to "bleed France white" by drawing troops from an enormous area to the defense of the fortress town. In his favor was the fact that Verdun formed a salient into German lines, allowing it to be attacked on three sides with an unrelenting bombardment. With its strategic reserve destroyed, France would have no choice but to seek a negotiated peace or risk a German breakthrough and a humiliating defeat.

Postponed because of freezing weather from its original proposed start date of February 12 to February 21, the assault was to be preceded by a 21-hour bombardment. Marshal Joffre, apprised of the imminent attack, duly rushed reinforcements to the French Second Army, while the fortress commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Emile Driant, attempted to strengthen Verdun's defenses. His 200,000 defenders, on the east bank of the Meuse River, faced a formidable foe: a million German troops of the German 5th Army under Crown Prince Wilhelm.

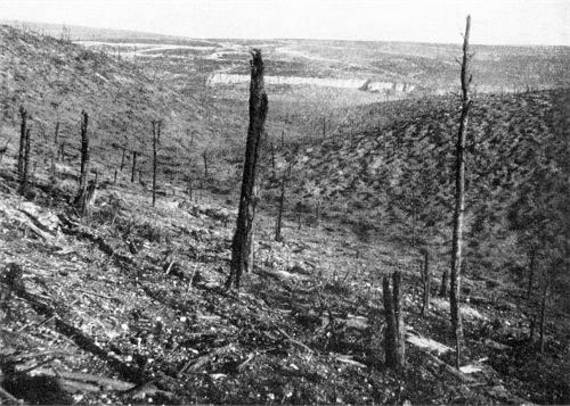

The Prince's opening gambit--100,000 shells fired every hour from 1,400 guns along an 8-mile front--was intended to wipe out the French defense before the infantry started their advance. It failed. Miraculously, half of the defenders remained in place. In response, Wilhelm renewed the bombardment, but by the end of the first day the Germans had succeeded only in taking the French frontline trenches. Meanwhile, French counter-attackers had been met for the first time by German flame-throwers. They were horrifying weapons but capable of only a short firing time and useless when empty.

On the second day the next line of trenches was overrun and the defenders had been forced back to within five miles of Verdun itself, although the outlying forts were still holding out and more reinforcements were on their way. When one of those forts fell, Joffre reminded his commanders that any man who ceded ground to the Germans would be court-martialed. To surrender Verdun was unthinkable. Joffre appointed Philippe Pétain--later to achieve notoriety as the Chief of State of Vichy France during World War II--to command the defense. "Ils ne passeront pas!" Pétain assured Joffre. "They shall not pass!"

It was a significant appointment. Pétain, determined to inflict as many casualties on the Germans as possible while conceding the inevitability of enormous French losses, reorganized the use of artillery and ensured an effective supply route remained open. The next German offensive, on March 6, met with stern resistance as French reinforcements continued to arrive. Of the 330 infantry regiments the French army possessed, 259 saw service at Verdun. On April 9 the third major German offensive started, again Pétain's defenses held and again attacks were met by counterattacks.

As the weeks wore on, Pétain was promoted and replaced by General Robert Nivelle. The Germans also started to use a deadly new chemical: diphosgene gas. Denser than chlorine gas, phosgene hugged the ground spilling over into the trenches with deadly effectiveness. But French forces still held. Their losses were horrendous, but so were the German ones. The German General Staff had other worries as well. The British were starting a major offensive in the Somme. It had been brought forward from its intended date as a means of diverting German manpower away from Verdun. In addition, a Russian offensive in the east was a further drain on resources.

The weeks turned into months, the French started to retake ground captured by the Germans and gradually the latter began to realize that von Falkenhayn's plan to bleed France white and take Verdun was never going to succeed. The Battle of Verdun dragged on until December 1916, having lasted nearly 10 months and cost both armies horrendous losses. Of 542,000 French casualties, 362,000 were killed. German losses were estimated at 434,000, of which 336,000 died. Neither side had gained any advantage. If France had bled, so too had Germany.