Madina, in a blue burqa, is a recovering multi-drug-resistant TB patient from Logar province in Afghanistan. Her nephew Khairullah helps her double-check the dosage of her monthly pack of TB medicine before they leave the hospital. Ahmad A. Fakhri/ UNDP Afghanistan

Madina, in a blue burqa, is a recovering multi-drug-resistant TB patient from Logar province in Afghanistan. Her nephew Khairullah helps her double-check the dosage of her monthly pack of TB medicine before they leave the hospital. Ahmad A. Fakhri/ UNDP Afghanistan

Kabul, Afghanistan-- A tiny woman with sunken eyes and her head covered with a scarf waits patiently in a queue to take her medicine for tuberculosis (TB).

Benafsha Mamonyar is in her early twenties and always dreamed of becoming a teacher. But this dream fell apart when she was 18 and contracted TB from a classmate in her hometown, Pulekhumri, a city in northeastern Afghanistan.

When people found out Benafsha had TB, they stayed away from her, even though she had been treated for some time and couldn't infect others. "Some of my relatives didn't want to be close to me, even though I used separate plates, cups and spoons," recalls Benafsha. "People kind of hated me and that was what really hurt."

The care she received from her immediate family helped her cope with discrimination over the six months she had to take first-line TB drugs. "Although my parents were sad for me, they'd always hug me and tell me I would get better soon," says Benafsha. Hope grew when her post-treatment TB test came back negative, but there was always the risk of relapse. Sadly, that's just what happened two months later.

The scourge of tuberculosis is huge in Afghanistan. More than a million people are believed to be suffering across the country.

Symptoms of TB include coughing, fever and night sweats. If diagnosed correctly, patients can be given a six-month course of "first-line" treatment and will have only a 3.5 percent chance of developing multi-drug-resistant (MDR) TB.

But if a patient is misdiagnosed and given antibiotics irregularly, they will eventually need an eight-month course of "second-line" drugs, and the chance of developing MDR TB shoots up to 20.5 percent.

Poor medical practices, including the prescription of insufficient or non-standard medicine and the incorrect use of drugs, are also drivers for MDR TB.

The Afghan Ministry of Public Health with support from the international community including UNDP has responded by equipping more than 3,000 health facilities with basic TB testing capabilities and first- and second-line TB drugs. In addition, GeneXpert testing facilities have been rolled out in Kabul, Jalalabad, Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif, cutting diagnosis times from eight weeks to a mere two hours.

At first, Benafsha was heartbroken that she had to be referred to a specialized TB hospital in Kabul, several hundred miles from her hometown. But it is the only facility in Afghanistan that treats multi-drug-resistant TB.

Here, Benafsha, was hospitalized for eight months to prevent the spread of her resistant strain of TB and allow doctors to supervise her drug regimen.

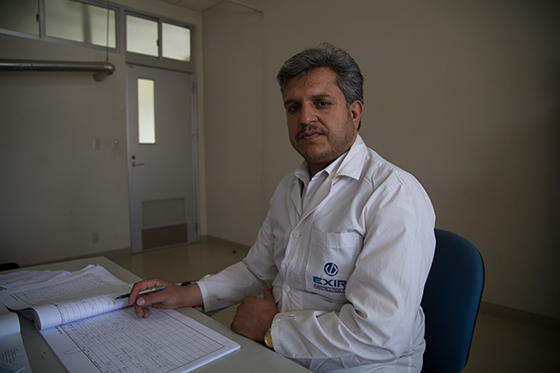

It is the end of a busy day for Dr. Hashim Khan Amirzada, lead consultant at the National TB Hospital in Kabul. Every day, he checks up on nearly 20 multi-drug-resistant TB patients and reviews their lab tests to monitor their treatment. Ahmad A. Fakhri/ UNDP Afghanistan

It is the end of a busy day for Dr. Hashim Khan Amirzada, lead consultant at the National TB Hospital in Kabul. Every day, he checks up on nearly 20 multi-drug-resistant TB patients and reviews their lab tests to monitor their treatment. Ahmad A. Fakhri/ UNDP Afghanistan

Right now, the MDR TB hospital in Kabul is treating 345 patients, of whom 47 are in-patients undergoing the initial eight-month treatment. After release, patients are required to come to the hospital once a moth for at least 16 months to collect medicine and get lab tests. Altogether, it takes two years for an MDR TB patient to recover fully.

But there will soon be a rise in diagnosis and treatment of the multi-drug-resistance TB with the new hospitals being built with UNDP support in Jalalabad, Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif. Each of these 24-bed hospitals will have the capacity of treating more than 200 multi-drug-resistant TB patients.

Benafsha soon realized that coming to this hospital so soon after her diagnosis was in fact been a real blessing. While there, she heard stories of patients who faced huge difficulties before they could get treatment. Patients like Madina.

Madina, 30, was brought to the hospital on a stretcher. "I was so weak and emaciated I couldn't come by foot," she says as she sighs. "I coughed, had trouble breathing and could barely eat anything."

Madina had been already treated irregularly for TB for more than two years back in her farming community in central Logar province. Madina could hardly read or write and was married with two children when she was first diagnosed. When she got too sick, a sister who had lost her husband to a suicide blast, had to look after her children. "My kids would cry, but I couldn't hug or attend to them," she recalls. "My children would ask me over the phone, 'Mom, when are you coming back?' and I couldn't stop my tears."

Before being admitted to the hospital in Kabul, she had almost lost faith in any hope of recovery. "I would say to myself that I won't remain alive," she says. Her husband was always beside her, but desperation and stress took its toll on both of them. "He once told me, 'If you're not getting better, why don't you die,'" says Madina.

Even so, being hospitalized for eight months was a tough decision. She had to be separated from her eight-month-old baby boy as she needed to be isolated and treated alongside other MDR TB patients.

She remembers the day when the doctors told her in front of a small crowd of family members that this was the only way she could reclaim her life. "There was a doctor I overheard saying that he saw enough courage and strength in my face to accept the challenge," she recollects with a nod. "And those words had a real impact on me, so I decided to stay."Now Madina has already completed eight-months of treatment in the hospital and another 11 months at home, leaving her five more months to go before she completely recovers.

Benafsha was also worried about going into hospital. All her family were shocked when told that Benafsha would have to stay for up to eight months as part of her treatment.

"Benafsha is a quiet, shy girl," says her brother, Nasir Mamonyar. "She never went anywhere by herself in the past and was always with the family. But despite our worries, we had to accept this to get my sister's life back."

"When three tests in a row are negative, TB patients are non-infectious and are good to leave the hospital and continue the rest of their treatment at home," says Dr. Hashim Khan Amirzada, the lead MDR TB consultant at the hospital.

In the past few years, Hashim and his team have successfully treated nearly 70 percent of their MDR TB patients. The treatment regimen is highly effective, but some patients quit taking drugs before the end of the course, especially when they are far from a health facility or too poor to keep buying medicine.

Luckily, for both Benafsha and Madina, the sacrifices were more than worth it. They're now back at home and are expected to make a full recovery within a few months.

"I feel as if I have been resurrected and granted a new life. I have started to be hopeful about my future," says Madina. Banafsha will rejoin her college in three months, while Madina will raise her three kids and and put them through school.