'Sculpture Victorious: Art in the Age of Invention 1837-1901' at Tate Britain aims at presenting Imperial Britain as elegant in spite of the obvious lack of restraint and excessive theatricality of their sculptures. Instead of deconstructing this paradox, the Tate show presents it as a scholarly fact. In fact, it is as if this exhibition were curated by the Victorians themselves.

Take, for example, one of the show's central pieces; Sir William Reynold-Stephens' 'A Royal Game' (1906-11) which presents a bothered Philip II of Spain trying to vanquish an elegantly hieratic Elizabeth I over a game of chess. Do the English think they embody elegance? Is this kind of art a visual representation of such a belief?

The representation of elegance in England has not always been that easy. It should be remembered that Henry VIII's conversion to protestantism and its consequent iconoclasm prevented indigenous painters and sculptors from enjoying the same level of patronage that they had in the continent. Although, Hollywood revisionism has tried to convince us of the fact that Elizabeth I snubbed Philip II, it would be fair to remind the Brits that, first and foremost, it was Philip II who had snubbed his first wife Mary Tudor by simply ignoring her. It was that same King who not only did gather the biggest art collection in the world (now at the Prado) but also singlehandedly commissioned and funded no other than the Escorial Monastery. While the Spanish monarchs were used to purchase Titians, Rubens and Velazquez, Elizabeth I had to conform with a lesser kind of royal portraiture. When we compare Spanish Habsburg to Tudor court portraiture, we see that while the Spaniards could display elegance through modesty (take Velazquez as an example), the British could not restrain from showing off their bling bling in whichever opportunity they found. I think in these islands they call this 'a chip on the shoulder'.

This taste for excessive ornament and historicist folly reached its peak in Victorian times when the English finally got the means to properly do what they like to do:; showing off. The outcome is for everybody to see in the Victorian sculptures included in this show. But do not take my word for it, let's read what The Daily Telegraphs' Richard Dorment has to say about this show: 'Sculpture Victorious is like nothing I've encountered in a gallery before. Its incoherence is frightening. The subtitle, "Art in the Age of Invention 1837-1901" makes it clear that this is not a conventional survey of Victorian sculpture. The organisers look at the medium in relation to such topics as the expansion of the British Empire, the gathering pace of the industrial revolution, technical and scientific innovation, and new sources of patronage by the state and church. Any single one of those subjects would have provided more than enough material for an entire exhibition.

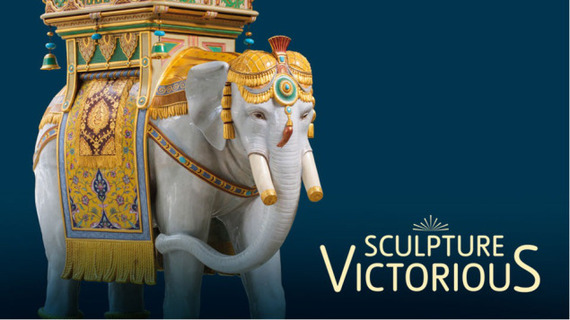

The show starts with a display of coins and medals that refers to the way Victorians wanted to appropriate Imperial Roman imagery. Visually these medals are disappointing and confusing. Not far from there there is the amazing Devonshire Parure, which should have been placed in the middle of the room but instead, it was put in a corner as if they were part of the development of an idea of elegance that included the Industrial Revolution, which is, obviously not the case. Not far from there we have the amazing lead and tin-glazed earthenware Elephant, modelled by Thomas Longmore and John Hénk for Minton and Co, which is displayed in a gallery otherwise dominated by Hiram Powers's neoclassical marble, the Greek Slave. What links the two works in the minds of the curators is that both were shown in International exhibitions - the Greek Slave at the Great Exhibition of 1855, the Elephant at the Paris Exposition of 1889 but that connection gets lost in a sea of confusion. To be honest, I left this show trying to know more about the Elephant. How did it function? How was it supposed to be displayed? It is as if the curators believed that technical prowess per se was a source of artistic value which, of course, is never the case. The question that this show brings about through sheer confusion is that of the notion of art in Victorian times. The fact that I left the Tate Britain without a convincing answer is, to say the least, worrying. Is this exhibition an example of how self deluded are the English since Victorian times? Maybe.