INTRODUCTION

Annie was sitting in front of her computer on her carpeted floor, Skyping me from her tiny living room in Eugene, Oregon. She listened to me, almost guardedly, as she drank her coffee.

Andrea was wide awake—it was four a.m. her time—as she sat alone in her room in Kenan Community (a kind of student housing) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She wasn't crying, but I could see her shaking slightly and breathing harder as she finished telling me what had happened to her one night at an off-campus party. "Me, too. It happened to me, too," I said.

"I believe you," Annie said, and with those three simple words, she became the first person to listen to my entire story of surviving sexual assault.

We shared our stories, we believed each other, and we promised to support each other through the entirety of our journeys.

Although we are from very different backgrounds, we had both been drawn to UNC–Chapel Hill by the school's competitive academics and by its strong sense of pride, by the lure of intellectual prospects and by the sense of community and belonging that all students applying to college yearn to feel.

We never expected to be writing a book before turning thirty, much less a book that would detail stories all too similar to events we each once tried to completely suppress.

Sign up for more essays, interviews and excerpts from Thought Matters.

ThoughtMatters is a partnership between Macmillan Publishers and Huffington Post

We never imagined that in our lifetime the president of the United States would say, "Survivors, I got your back," or that revelations about the scope and institutional cover-ups of campus sexual assault would be on the front page of the New York Times, or on the cover of Time magazine.

But we also never thought that, in our lifetime, we would survive violence.

We've noticed, even with our own stories when we've told them ourselves, that the media often leave out the messy details, as if pining for a "perfect survivor" narrative, something which we have come to learn does not exist. Not everyone was sober when she was assaulted. Not everyone went on to triumph after his experience of sexual violence. With this book, we wanted to delve into the gaps, into the stories the mainstream media often deem not pretty enough to retell; we wanted to share real stories and to make sure to include some of the survivor identities and experiences that are too often dismissed.

The stories of what happened to us, along with thirty-four other individual stories of assault and sexual violence, of betrayal, and of healing, unfold in the pages that follow. We know that there are many who do not want to speak out, or who cannot tell their stories, or who were forever silenced when they tried to speak out. And the thirty-six of us in this book cannot speak for them, but we carry them in our thoughts as we share what happened to us.

PART I

BEFORE

Six years ago, I tore the blue seal of the large envelope that held my acceptance letter to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). I came from a tight-knit Cuban family that had never had the opportunity to even consider college. I was going to be the first one in my family to make it, and I loved everything about Carolina.

—Andrea Pino, survivor who attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

To understand our journeys of healing and survivorhood is also to understand that we live in a culture that warns us to avoid the moment when sexual assault will break us, as if we could avoid that moment—a culture that tells us what clothes to wear, what signs to give, what signs not to give, and what not to drink, as if by making such personal adjustments we might have the power to avoid the violence done onto our bodies against our will.

Even before sexual assaults occur, we live betrayed by a society that blames us for any violence that might happen to us—and blames us for our gender performance or for our lack of femininity or masculinity, and blames us for our willingness to challenge these rigid social expectations, as if these facts about us, as if these qualities inherent in our identities, warrant violence.

Before sexual assault, we were children told of the adventures that awaited us in college—"the best four years of your life!" We were courted by pristine, colorful brochures that invited us, encouraged us, to ask big questions and to contribute to a community that wanted us.

Before sexual assault, there was an element of innocence within us, an innocence that bought into the belonging that the colleges and universities advertised.

We were customers, but we were also dreamers.

Before we were sexually assaulted, the colleges and universities sold us trust, love, and safety; and we bought in with our tuition dollars and our hearts.

THE ATTACKER

A Chorus

We'd kinda been friends my freshman year.

He was an acquaintance; we had the same friends.

I had met him in passing the year before. Seen him around campus. He was a visiting student.

He was a fellow athlete and was in one of my classes.

Met him at a frat party. He was not a frat member, just a guy who was there.

I was raped by a woman, an upperclassman.

This guy had dropped out and was no longer a student, although he was hanging around.

The cops knew all about this guy. He had already raped six people and attempted to rape three others.

He was someone I had considered one of my best friends.

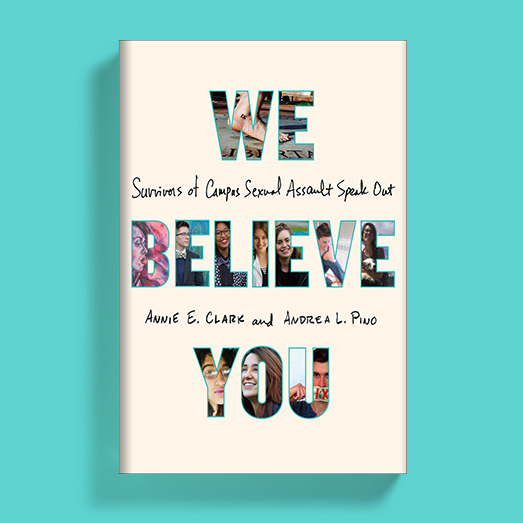

Copyright © 2016 by Annie E. Clark and Andrea L. Pino. Excerpted from We Believe You: Survivors of Campus Sexual Assault Speak Out

In 2013, Annie E. Clark and Andrea L. Pino, along with others, filed a federal complaint against the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for mishandling sexual assault reports; since then, students across the nation have filed similar complaints and the government has opened more than 200 investigations. Clark and Pino are two of the founders of End Rape of Campus, an organization providing support for survivors and working to end campus sexual assault. Their stories are prominently featured in the award-winning documentary The Hunting Ground. They are two among many, tirelessly seeking justice on behalf of survivors.

Read more at Thought Matters. Sign up for originals essays, interviews, and excerpts from some of the most influential minds of our age.

___________________

Need help? In the U.S., call 1-800-656-HOPE for the National Sexual Assault Hotline.