"I tell you what... the show is being recorded and televised for England and uh they told me, they said uh you gotta do this song, you gotta do that song, you gotta stand like this or act like this. They just don't get it man, I'm here to do what you want me to do and what I want to do." -- Johnny Cash at San Quentin prison

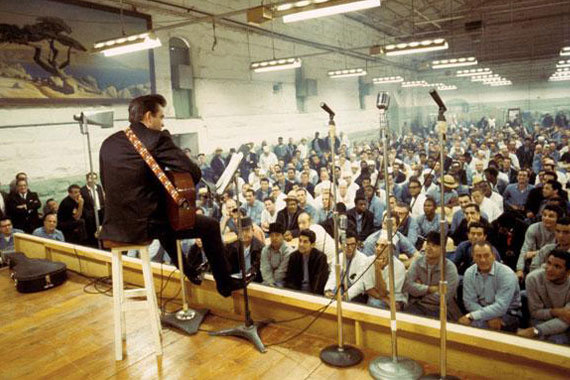

On February 24, 1969, one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, Johnny Cash, recorded an album in San Quentin State Prison in California. The recording of the album itself was controversial -- many conservative voices didn't understand why criminals should have the luxury of being entertained. During the concert, Cash made irreverent jibes at the prison wardens, joked about how everything was served in tin cups and played up to the crowd. When asked what he thought about the prison wardens he, in a now iconic photo, gave them the middle finger.

Cash was sure that the album would be a great product and critical reception vindicates his opinion. But through his actions, and the above quote, he was not only giving the middle finger to the establishment, he was also saying that regardless of what those in power wanted, what was more important was doing what the prisoners and what he wanted. It was a powerful message.

Cash's message has clear relevance for global development, a highly complex system in itself. In a world where there are so many issues to work on, those in positions of power will naturally address issues that they identify, while some others fall to the wayside.

Johnny Cash at San Quentin. Photo: uncut.co.uk

In Cambodia, where I have worked for the past three years, there are some incredible changes occurring in areas of need. We've seen huge progress -- the rate of HIV in Cambodia has dropped from 2 percent in 1998 to 0.4 percent in 2015. In malaria, there were approximately 10,000 deaths in 1992. In 2013, there were 12. This progress is quite simply staggering. But there are other areas that have been left behind. The system addresses many issues and people, but not all.

Srey Ran, a 12-year-old girl from rural Cambodia, who I met this year, is someone who, up until recently, the system had left behind. As a child born with Down Syndrome, she not only looks different, but the way in which she communicates is different. Often resorting to using hand gestures or scratching messages in the dirt, people assumed that going to school would be too difficult a task for her. Indeed, without the right support, there is no way that Srey Ran would ever have a chance of an education.

When the United Nations created the Millennium Development Goals in 2000, a set of eight overarching goals to guide the way that countries were to develop, they set goal number two as achieving "Universal Primary Education". That is, the goal was for all children, boys and girls, to complete primary schooling.

In response to this, the United Nations Girls' Education Initiative (UNGEI) was established to close the gender gap and focus specifically on getting girls into school. There are a host of other wonderful initiatives out there that aim to increase the enrolment of girls in schools.

Despite this, goals and initiatives have not addressed the needs of children like Srey Ran. There are many reasons for this, of which one is the complete absence of the word "disability" in the Millennium Development Goals, a bizarre oversight that meant that an estimated 1 billion people with disabilities around the world were instantly ignored. Thankfully, the Sustainable Development Goals, recently launched in New York, endorses inclusive education for all children, including those with disabilities. How this plays out in action is yet to be seen.

For Srey Ran, as a child with a disability, she requires specific care. Her language development was delayed, so she required speech therapy to get her into school. But there are no global goals, no global initiatives, and no pathway for the system of global development to develop speech therapy as a profession in countries like Cambodia.

If Srey Ran had been born in my home country of Australia, she would have received speech therapy from any number of the over 7,000 speech therapists in country. But she was born in Cambodia, where there is not one Cambodian university trained speech therapist.

Fortunately for Srey Ran, we were able to train her community worker, Phearom, in basic speech therapy and she worked hard with her for months. Her speech became more controlled. Her confidence started to improve. She no longer had to rely on her hands to communicate, she started communicating with her mouth.

At the age of 12, Srey Ran started to go to school for the first time. The girl that no one thought would have a chance at education proved everyone wrong.

At a global level, if there is such momentum behind getting children, especially girls, into school, why do some children like Srey Ran get left behind? Ultimately, there is a mismatch between the global agenda and what's needed on the ground. As Johnny Cash intimated, we're often not doing what people really want us to do, or what they really need.

The system of global development cannot address every single person and issue of need. There will always be some who are left behind. But I believe that where these gaps occur, it requires individuals, small teams of dedicated people, to fill these gaps. This is where initiatives like OIC: The Cambodia Project can add real value. We believe that no one, regardless of how off the international radar they are, should be ignored.

When Johnny Cash recorded At San Quentin, nobody knew really what he was going to do. Even his own band had to improvise the backing for a song they had never played before, "A Boy Named Sue", that Cash spontaneously decided to play on the day. They made the best of the reality of the situation. "A Boy Named Sue" went on to win a Grammy for the Best Male Country Vocal Performance.

Getting Srey Ran into school is all about making the best of the reality. We may not be able to change the way the global agenda is set, but we can give people what they really want, and what they really need.

You can support our recently launched program to get children like Srey Ran into school here.

Weh Yeoh is the founder and managing director of OIC: The Cambodia Project, which aims to establish speech therapy in Cambodia for those with communication and swallowing disabilities. oiccambodia.org