Every day, for the past 15 years, Christine Armstrong sits at her computer and scans the overnight news stories for deaths related to domestic violence. These days, she limits her research time to four hours a day. Well, she tries anyway.

Every day, for the past 15 years, Christine Armstrong sits at her computer and scans the overnight news stories for deaths related to domestic violence. These days, she limits her research time to four hours a day. Well, she tries anyway.

Her quest began in 2000 when Armstrong had a personal brush with domestic violence and then helped a friend escape an extremely dangerous marriage. At the time, she was living in New York City working in the television business. Her experience prompted her to learn everything she could about domestic violence. After her research revealed how prevalent domestic violence homicides were around the country, she was surprised she wasn't able to find any documentation other than a few hundred names on a national organization's website. Horrified, and knowing there there were many, many more victims as a result of her own investigation, she began searching them out and documenting them with calendars.

Today in 2015, she has honed a sophisticated practice of conducting news searches that scour the web using over 27 different keyword combinations that turn up homicide stories every day that the media doesn't always correctly identify as domestic violence related. This unfortunate practice of "missing" the domestic violence connection to homicides is one that has been well-documented in academic and journalism circles. According to researcher Lane Kirkland Gillespie, assistant professor in the department of criminal justice at Boise State University, "Recent studies find only about one-quarter to one-third of news stories utilize language that identifies the homicide as domestic violence; and a lesser amount, 10-15 percent, specifically discuss intimate partner homicide in the context of domestic violence as a broader social issue." (See her academic paper on the subject.)

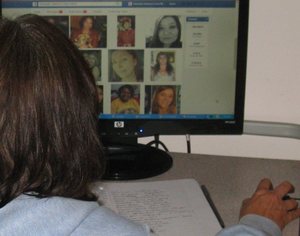

Soon after she began her record-keeping, Armstrong started volunteering in the field educating others about domestic violence. She kept up the chronicling of domestic violence homicides from 2001 to 2004. In 2005, she relocated to Alabama and went to work for a local shelter where for the next seven years she would continue to research the stories, keep calendars, notebooks, and spreadsheets of data as part of her day job. She eventually built a website,  and launched a Facebook page where she could post daily stories for the public. That Facebook page has grown to more than 28,000 fans with thousands of posts over the last few years. She left the shelter in 2011, and two years ago she had to take the website down, as it was difficult to justify the expense and time maintaining the platform.

and launched a Facebook page where she could post daily stories for the public. That Facebook page has grown to more than 28,000 fans with thousands of posts over the last few years. She left the shelter in 2011, and two years ago she had to take the website down, as it was difficult to justify the expense and time maintaining the platform.

Yet, her work has continued even though now she is employed outside the field. Publishing at least a half dozen different news reports a day, she tracks it all: women, men, parents, grandparents, children, neighbors, co-workers, law enforcement officers, and any other bystanders impacted by these crimes. On average, Armstrong is documenting approximately 1,800 names a year that have been directly touched by domestic violence homicides. Her spreadsheets contain over 14,000 names. She keeps a running list of missing and unsolved cases she's turned up over the years. The list includes more than 800 missing women where domestic violence is known or is believed to have been a factor in their disappearance. You can see their photos on her Facebook photo albums.

I do this work because, to my knowledge, no one else is doing it and many of these victims aren't even included in domestic violence statistics. A lot more people are dying from domestic violence crimes than most people realize. These are real people with lives. Their loved ones have been in touch with me and would like to see some good come from their loss. -- Christine Armstrong

As difficult as this work is, Armstrong perseveres. What's most alarming to her is how little things have changed over fifteen years. She sees the same stories in 2015 she saw in 2001. The stories reveal how common it is for a domestic violence homicide suspect to have several contacts with the police and the courts with little or no consequence. She notes that with 18,000 separate police departments and justice systems in the country, progress is sketchy and piecemeal. The quality of service a domestic violence victim receives largely depends on where they live, and sadly, the majority of law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and judges don't know how to recognize a domestic violence case when the clues are so obvious. "Rarely does a day go by that I don't see a story where some law enforcement officer, prosecutor or judge declined to intervene in a high risk case and now another person is dead," she says.

Armstrong points out some of the worst to suffer are the thousands of children who have lost one or both parents to domestic violence. Even worse, many have witnessed the violent deaths of one or both of their parents. Left orphaned, many end up in the custody of the state and in foster homes.

One trend Armstrong has observed is particularly troubling. Her data reveals there are more homicides stemming from dating relationships than married relationships in the past few years. Advocates have long been seeking equal protection in dating relationships, particularly as it relates to protection orders and removal of firearms. Progress has been slow, yet the body counts mount.

As a whole, Armstrong feels we don't seem to be learning much from our mistakes. A lot of the change that does take place, seems to take a tragic death and a high profile lawsuit to make it happen. She's disappointed and somewhat shocked in light of recent national media attention that there isn't much unity in our national response to this chronic social epidemic. She says, "While response has improved in some of our communities, much work still needs to be done - an incredible amount of work."

Armstrong is doing her part.