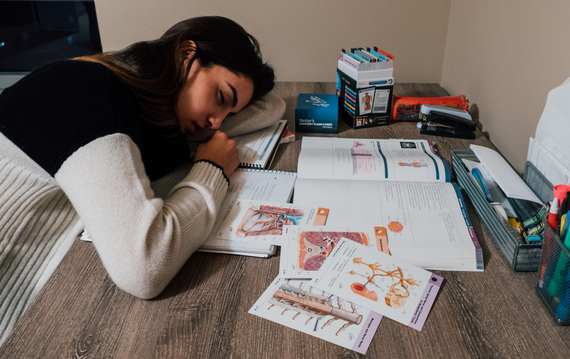

The irony was not subtle -- an 8 a.m. lecture on sleep to which most of us showed up sleep-deprived and in desperate need of caffeine. Sitting in the lecture hall and yearning for the exact thing I was supposed to be taking notes on, I began to think about how my notion of sleep has changed in medical school.

I'm huge on sleep, mainly because I turn into the monster version of myself when I don't get enough of it. In an environment where it is expected -- and sometimes even seems trendy -- to not get enough sleep, it has been hard to remain steadfast with my habits. After starting medical school, time became my most precious resource, and I started to wonder if I was wasting it away in my bed. So, as most medical students would do, I took to the research to answer my questions.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends 7-8 hours of sleep per night for adults, with some variation from person to person. Insufficient sleep is associated with numerous chronic conditions including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and depression. According to the CDC, "getting sufficient sleep is not a luxury -- it is a necessity -- and should be thought of as a 'vital sign' of good health." Vital signs, like blood pressure and temperature, are indicators of how our bodies are functioning. In the same way, the amount of sleep we are getting impacts our functioning in a profound way.

In a study of 314 U.S. medical students using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, medical students' quality of sleep was significantly worse than a healthy adult sample. While it may seem obvious, this finding has important implications for medical student performance and well-being. Sleep deprivation has consequences for cognitive function, namely for attention and memory, two of the most crucial functions for any medical student. A study of the impact of sleep loss on neurobehavioral performance showed that, on a test of multiple components of cognition, 20 to 25 hours of wakefulness produced equivalent performance decrements to a blood alcohol concentration of 0.10 percent. If drinking alcohol before an exam is ludicrous, shouldn't an all-nighter be too?

As future advocates for patients and proponents of their healthy living, we should set an example for healthy living ourselves. The Institute of Medicine estimates that 50 to 70 million U.S. adults have a sleep or wakefulness disorder. In primary care patient populations, sleep problems can be particularly prevalent. One study of almost 2000 primary care patients identified one-third with insomnia and over one-half with excessive daytime sleepiness. Moreover, reduced sleep time is associated with increased prevalence of obesity, a growing concern for patients and physicians alike. Understanding the challenges of getting enough sleep and being able to thoughtfully counsel patients on how to improve their habits could impact their lives in major ways.

In the first two years of medical school, most of us are not making clinical decisions that will affect patients. What we are doing is creating habits for ourselves as future physicians who will be making those impactful decisions. If we do not find ways to make time for sleep now, we will face greater difficulty in finding balance when the hours become more demanding in our clinical years, in residency, and beyond.

For now, we will be more attentive, improve our memories, and make better decisions if we carve out a little more time for sleep each night. Some of the challenges come with the territory, with generations of physicians to attest to the strain medical school placed on their sleep schedule. That doesn't mean we can't make improvements.

Arianna Huffington has discussed a sleep revolution and how sleep will determine "our ability to address and solve the problems we're facing as individuals and as a society." Though being well-rested may not be the norm in medical school, we can change the conversation. Instead of bragging about how we are "functioning" on four hours of sleep, let's start bragging about our eight-hour nights.

The Institute of Medicine Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research posits that awareness on sleep deprivation and disorders is low among health care professionals, considering the magnitude of what they call an "unmet public health problem." Medical school education is a worthy first step. If we dig into the benefits of more shut-eye, we can start a revolution to set the example for patients in years to come.

As the lecture came to a close, the professor left us with a quote from Allan Rechtschaffen, sleep expert at the University of Chicago, reminding me that my hours in bed were well-spent.

"If sleep does not serve an absolutely vital function, then it is the biggest mistake the evolutionary process ever made."