Like most kids of the Reagan generation, before social media and smart phones or Oval Office trysts, I grew up collecting comic books. I was collecting at a time when comics where heroic, a-sexual, safe, and non-ambiguous. Comics were clear moral tales of good versus evil. There were no antiheroes with deep-rooted psychological issues, just a post-Cold War James Bond saving the world with super powers in Halloween outfits.

My favorite comic book was the X-Men, so naturally a started collecting the spin-off X-Men-in-training series, The New Mutants. It wasn't until the jaw-dropping, head scratching issue of New Mutants #18 in August 1984 that irrevocably changed my perception of comic book art forever. Enter artist Bill Sienkiewicz who drew issues 18-31 in such an expressionistic approach that became vast departures from his predecessors Bob McLeod and Sal Buscema.

Bill Sienkiewicz's painting style used mimeograph, collage, watercolor and oil painting to get wickedly absurd superhero imagery that was far from the cartoony look. The look of Sienkiewicz's Electra: Assassin and Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns soon became so prevalent in the rated R, PG-13 graphic novels that it eventually became the norm.

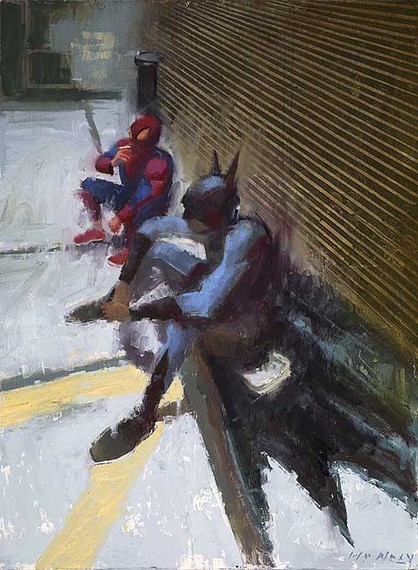

Like Sienkiewicz, William Wray, conveys disturbing undertones in his Superheroes Series as grisly despair-trodden, anti-mythos that we don't typically see in Hollywood films. Wray uses modern day irony by portraying the faux superhero street peddlers of Hollywood Boulevard luring wanton tourists to get a picture with them at the Mann Chinese Theater through his oil paintings. Wray paints Batman on his cell, a portly Captain America waiting at the men's room, scrawny Spider Man seemingly heart broken on a fire hydrant, Daredevil at a urinal and Batman sharing a cigarette with Spiderman.

However, despite the social commentary behind Wray's comic hero satire is a loose painterly plein-air approach. Wray never shies away on who his influences are. On my studio visit where I shot Wray's film in a quiet neighborhood in Pasadena, California, Wray educated me on Raimond Staprans architecture of flat composition, J.C. Leyendecker's role during the Golden Age of American Illustration and Richard Bunkall's brooding urban landscapes.

In my conversations with William Wray I asked why "Superheroes?" Wray explains when referring to religious overtones, "they are metaphors for society's need for a immortal savior." Wray believes that average people fantasize about saving the world and that some go as far as dressing up as superheroes at comic book conventions where "they are rewarded with attention, even love, especially the street performers on Hollywood Blvd who fantasize about making it in Hollywood so they can pay their rent or drug habit through the tips they get from tourists posing with them. Some are "straight performers" who want to be considered legitimate " ambassadors to Hollywood" others are street hustlers scamming and strong-arming tourists."

William Wray believes he is doing a combination of satire and pathos. Wray uses irony to make a point, "Batman has to use a cell phone? Superman has to wait for a bus? Captain America has to fill out paperwork with the hotel valet? A hero needs to use the bathroom? These are mundane moments of real life that bring our Heroes down to earth with the rest of us. I avoid the fantasy pose and go with the real moment so we can peek past the mythos and into the mundane."

As far as Wray's love for comics, he says, "I was first attracted to the hero myth of comics as a child, but having an unhappy home life made me question the worlds presentation of morality and normal life as it was not happening at my house. Mad Magazine was the door opener. Their parody of Superman became my stepping-stone to questioning societal myths. I wanted to be an underground cartoonist. I did that for a while, but it was a dead market. Then I did regular comics and as many satires of them as possible. My current superhero paintings of the "mundane mythos," has become full circle of what I always wanted to do as an artist.

Ultimately, William Wray likes to spin his own tales of American Capitalism disillusionment and Liberal Social decay. Wray is not concerned about chiseled chests, shiny gadgets and dazzling superpowers, he is concerned with facial hair, morning breath and bowel movements of these metamyths. Wray told me he was never into comic books like I was, but more into the social sickness motif that is overwrought in his paintings. In the '80s we were all afraid of mutually assured destruction with the Soviets, in Wray we are afraid oh the mutually assured ridiculousness within us all.

See the film I did on William Wray below: