credit: Palais de Tokyo

Toxic bubbles.

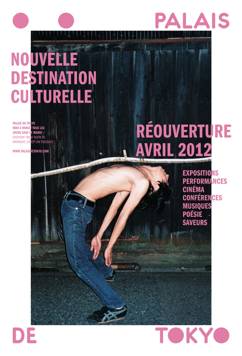

That's what Jean de Loisy wants his visitors to face on April 15 when they first approach the newly restored and re-opened Palais de Tokyo, which he claims will be the largest site for contemporary art in Europe -- or, for that matter, in the world.

"Art has to be venomous," he told me as we plopped on our hard hats to prowl up and down four levels through a labyrinth of broken blocks, raw columns and fiery welding torches three weeks ago to finish up the renovation job.

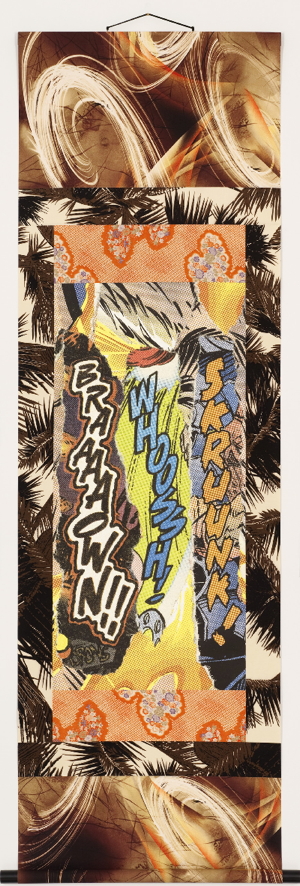

Venomous not as deadly but as sharp and stinging, art that marries beauty with provocation, underlain with persistent anxiety. It begins with the seven high elongated windows facing the Avenue du President Wilson captured by the Swiss-American artist Christian Marclay in the form of bright, color-clashing Manga bubbles. "Even when you are outside the Palais de Tokyo you can already hear through [the Manga images] the rumors, the voices, the screams , the expression of what's happening inside" de Loisy says. And, indeed, on entering the main hall a genuinely upsetting twisted burnt metal sculpture the size of a private plane seems to leap out from the wall and ceiling, a piece by Belgian artist Peter Buggenhout that was far from finished on my late March visit.

Credit: Palais de Tokyo

Hand scrawled on the wall are an array of zen-poetic lines: Arpenter l'intervalle [Measure the gap], La question du pouvoir est la seule réponse [The question of power is the only answer], La precision des terrains vagues [The preciseness of wasteland], Devenir grain de sable [Become a grain of sand], La sortie est à l'intérieur [The exit is within]. Turn back toward the opening and you are confronted by a painting that is the surface of a wall made up from layers of toxic materials as her medium. And on the other side, to which you arrive much later, is an oddly translucent work, again engrained into the wall and composed of sticky colored smoke that seems to invite you into itself.

"You have to dive into obscurity," Jean de Loisy argues, just as the shocked viewers of Cezanne and Van Gogh did in the 19th century or as our grandparents did with Rauchenberg or Max Ernst or Picasso. "Yes, you have to dive into obscurity," he repeats registering my uncertainty, "and you will arrive in other places with artists which gives you other feelings. And that is where the exhibitions are. You will see this and then the temporary exhibitions, but it creates a stability of the feelings... and that's what we want to create in the building."

De Loisy calls the opening works "interventions." The sculptures and paintings seem to be birthing themselves directly through the stripped and battered architectural structure, redesigned from the original 1937 museum by the minimalist architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. Though the Palais de Tokyo is hardly the first "art museum" to be drawn up as itself an engaged piece of art -- there remain the Moma, Frank Gehry's Museum on Main in Santa Monica, the temporary and now rebuilt Stedelijk in Amsterdam and not least Jean Nouvel's Arab Institute on the Seine here in Paris -- it proposes surely one of the most radical visceral journeys of any recent house of art. De Loisty, who seems to spend as much time in LA as in Europe, likes to call the Palais de Tokyo a sort of monumental Harlrquin:

"You know the costume of the Harlequin is composed of bits and pieces of fabric from the poor and the rich and the workers, all the people of the society. This "museum" is the place where I can gather all the parts of the society to be in the scene. It will look like... like a curtain of a theatre. It means now you have passed under those dangers [at the entrance] and now you enter in a poetic world where you can discover the artist."

Well, OK. But at the same time this idea of a museum, somewhat reminiscent of the ethnographic art and garden museum just across the river, the Quai Branly, also forces us to address the question raised by the German critic Boris Groys. Groys, who grew up in East Germany, argues that in our marketized universe, advertising and the Internet have created a world exactly the inverse of what art meant in the 19th and 20th centuries. "The Internet and digital media have completely changed mass culture," he told the interviewers for the new book The Future of Art. "It has changed insofar that people watch and read less than they write and show. The premise of mass culture had been the passivity of the masses. [Critics before] wrote about the society of the spectacle [where] the masses are masses of recipients and then there are producers who delude or create illusions for them. No there are no more of these kinds of producers."

Credit: Palais de Tokyo

Now all the middle class -- to the extent it exists -- is driven to make their lives into pockets of representational art. Digital movies. Global cuisine. Confessional memoirs. All of it created and exchanged, sometimes with passion, occasionally with graceful design and exchanged day after day on Facebook and catalogued by Google. Museums, which are popping up faster than digital mushrooms, have become in Groys' view habitats for relics that increasingly are more and more remote from traditional "art consumers" in the commercial art industry. A few famous names -- Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst best known -- pass through the fairs and auction markets along with the masters of earlier centuries, but their work has little to do with the hundreds of millions who make up the Facebook art exchange masses.

Credit: Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center

(The current show, Spectacle, at the Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center, the art display palace designed by Pritzger Prize Winner Zaha Hadid, makes the point even sharper. Its current six-month show on the history of video art includes an entire room dedicated to interactive video where the point is that social media networks make it possible for us, the consumers, to take over any image, any sound that Google and Yahoo can find and convert it into works of our own that we can then distribute to tens of thousands of other art consumers who in turn can -- and do -- refabricate it over and over into an infinite geometric pyramid of fluid personal art.)

Result of all this: art museums have, in less than two decades, or half a lifetime, found themselves transformed into high order "Fun Houses" (after Cedric Price) that must also offer film halls (there will be four at the Palais de Tokyo), impeccable coffee in various blends, splendid luncheons at reasonable prices (Tokyo's restaurant, which opens this summer, will seat 400 giving directly onto a footbridge across the Seine to the Quai Branly) and gathering halls to hear, see and be seen beneath and between the venomous walls and tortured sculptures.

Contemporary art, the Palais de Tokyo, is no longer and can no longer be the special terrain of the aesthetic courtesans to remote powerful elites: it is the collective carnival gathering in which we are inundated by the sounds, sights and symbols of our current collective madness.