This review is co-published with Duke University Press in its journal Cultural Politics. Duke University has generously provided open access to the art content in the Cultural Politics archive starting with Vol 8, 2012. Read more articles like this one in the Cultural Politics portal.

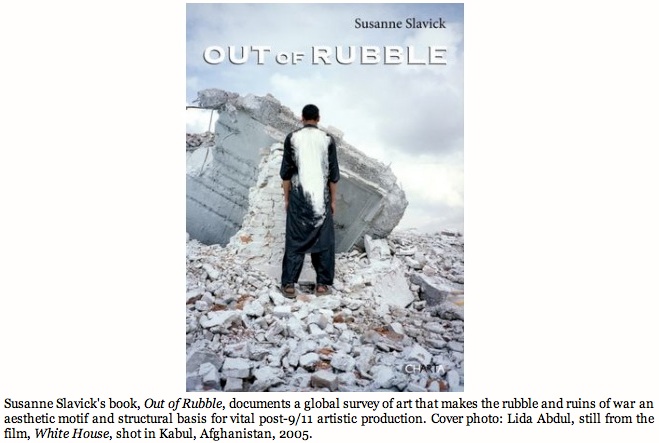

There is no superiority in the experience of war. At least, so goes the wisdom championed by pacifists for millennia. Yet the myth extolling the virtues of war veterans--be they military or civilian--is gratuitously resurrected at the outset of Susanne Slavick's Out of Rubble, a book that functions as much as an exhibition of vitally relevant visual art made in the wake of 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as it does an essay on how the signage and embodiments of war, specifically the remains and evidence of war's aftermath, have come to dominate the aesthetics and artistic production of politically minded artists of the previous decade.

Rubble, it turns out, is more than a ubiquitous gravel and detritus in the hands of the artists of the twenty-first century. It is even more than the signage and embodiment of war and devastation. Rubble has evolved into a globally encompassing cipher for that singular wisdom shared by those elected as reverse elite by the chance forces of war, unified by their sudden victimization and impoverishment.

Slavick is purposely vague on whether she subscribes to the myth of war as ennobling to humanity. But considering that a number of the artists in her survey clearly make work that is largely or wholly informed indirectly through the media, she leaves us perplexed, and a trifle troubled, as to why she invokes the myth of wartime ennoblement to begin with. Slavick does proceed to counterpoint the valuation of the firsthand experience of war--and thereby justifies the art made by artists with only indirect experience--by compiling a succession of citations made by prior writers on the necessity for empathy in any art of war. But in so doing, Slavick neither speaks out against the militaristic valuation of wartime experience, nor does she endorse the view that the art of war produced by media-oriented artists is as meritorious as the art made by the artist-veterans of war.

This is only the first of instances in which Slavick reprises a myth that has been devalued by recent generations of artists and public, to counter with the current valuation of the issue before moving on without either dismissing or endorsing it or attempting to reconcile either of the views she has just unearthed. If neutrality is her aim, Slavick might have pointed us to the fact that the military model for evaluating the art of war hasn't been applicable to wartime art in the West since the late nineteenth century--the last time that painters who glamorized war were made canonical to art history.

Perhaps Slavick is playing devil's advocate, spurring us on to reminding ourselves that the tradition of glorifying war in art was laid to rest on that day in 1863 when Mathew Brady produced his daguerreotype that famously changed the world. Federal Dead on the Field of Battle of First Day, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, with its depiction of rotting soldier-corpses, made it impossible to ever again return to a serious consideration of the aesthetic and romantic valorization of war, as had been imagined by painters and sculptors for millennia before the notion of propaganda was conceived. We know how the reality principle of photography was revised by every wartime generation and every advance in photographic media, whether in the depiction of trench warfare brought home from World War I, the corpses strewn across Nanjing and the Normandy beaches in World War II, the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, the Highway of Death in the first Gulf War, or the torture and humiliation of Abu Ghraib prisoners in Iraq. But unlike the Myth of the Glory of War, the Myth of the Superiority Found in Surviving War lingers with the help of photography, for the obvious reasons that it consoles the surviving victims and awards the bravery of soldiers.

Despite the sentimentalism that permeates so much journalism, the reality of war has held sway in recent U.S. presidential elections, namely, in the victory of civilian Bill Clinton over the war veterans George H. W. Bush and Robert Dole and again in the recent victory of civilian Barack Obama over erstwhile prisoner of war John McCain. Yet there are at least two circumstances that compel us to consider Slavick's motivation for resurrecting the military bias for civilians; it may be justified, at least ironically. In keeping mindful of the wars that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and its allies have led in Eastern Europe and the Middle East in the past two decades, the militaries of Western governments have shown how well they learned from the liberal media's close observation of the Vietnam War, to the extent that they today banish journalists to green zones miles removed from the front lines--except when embedding them within military campaigns, with all their attendant restraints, censorship, and disinformation. The U.S. government also sought, but failed, to legally ban the media from the funerals of fallen soldiers. Considering the West's continued financial and cultural ties with military-backed governments, occupying powers, and parliamentary governments under threat of civil war, it may be no exaggeration to say that we find ourselves assimilating military perspectives into our media and art at a level comparable to that not exercised since the early 1960s, a time when the world political theater was dominated by Charles de Gaulle in France, Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy in the United States, Juan Perón in Argentina, Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt, Nikita Khrushchev in the Soviet Union, Mao Tse-tung in China, Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan, and Fidel Castro in Cuba--all of these men championed to lead their nations during peacetime on the basis of their wartime achievements.

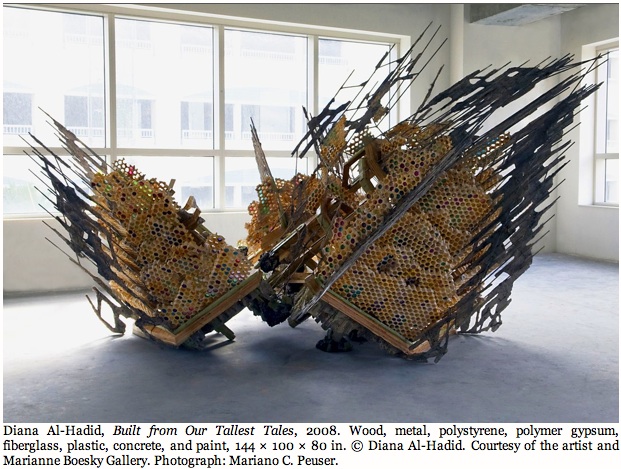

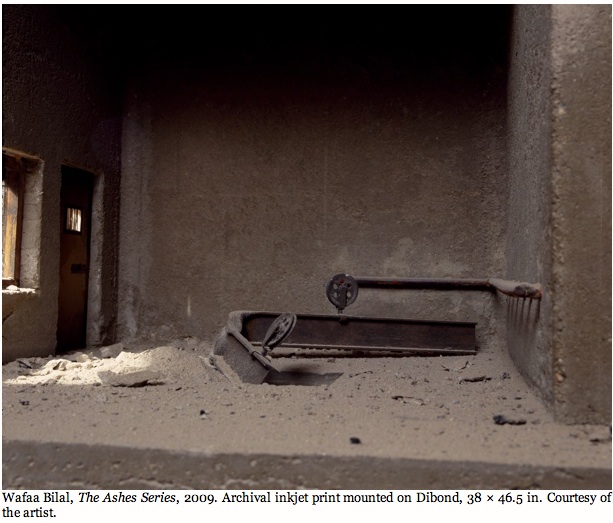

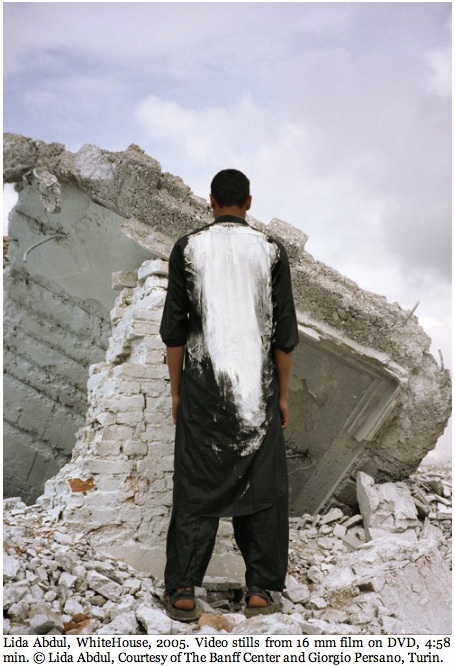

There is another, more pressing reason to review the military model. One look at Slavick's roster of artists informs us that she has compiled a globally representative selection, with a good number hailing from nations that have developed historically outside the Western avant-garde and its devaluation of art made in the service of state, church, and class propaganda. With Lida Abdul from Afghanistan; Adel Abidin from Iraq; Diana Al-Hadid from Syria; Taysir Batniji from Gaza; Xu Bing, Liu Bolin, and Xu Zhen from China; Osman Khan and Samina Mansuri from Pakistan; Julie Mehretu from Ethiopia; Simon Norfolk from Nigeria; Walid Raad from Lebanon; Armita Raafat from Iran; and Rocio Rodriguez from Cuba, more than one-third of the artists gathered by Slavick have experienced their primary enculturation in nations that, in many cases, have only in recent decades emerged from colonial rule, some of the nations having been wracked by wars during the artists' lifetimes, while others continue to be governed by despots and military occupations. Such an expansive representation at this point in the developing global agora of art urges us--as it obviously did Slavick--to reprise the debate on whether or not surviving war somehow makes us better, wiser, more responsible citizens and spiritually more enlightened leaders--if for no other reason than that this is a prejudice that still vitally propels the military backing of the administrations and regimes in several of these states.

As if to counter our discreet slide back into the international military rationale, Slavick's book in many regards offers the legatees of the cultural avant-garde reassurance that an unprecedented number of artists from around the world openly demonstrate their democratic and pacifist affinities with the artists and liberal-to-left public in the West. If Slavick refrains from exposing the demagoguery of the military model that holds veterans of war as somehow more valorous, and of electing the war veteran to lead while the mere civilian is deemed unqualified or even cowardly, then it would seem that Slavick's first concern is for protecting the artists and their families from retaliation by reactionary regimes. It helps to remember that in the time frame in which Slavick produced her book, artist Ai Wei Wei in China and film director Jafar Panahi in Iran were arrested and imprisoned by their respective authorities for making "subversive" statements and art. In July 2011, the elderly parents of émigré Syrian composer and pianist Malek Jandali were attacked in their Damascus home in retaliation for the performance Jandali gave at a protest rally outside the White House against the regime of Bashar al-Assad and in support of the Syrian uprising.

One myth that Slavick might have better left dormant for its having so little influence today concerns the so-called beautification of tragedy and suffering through art. On the surface, the myth is a fallacy by the mutual exclusion of its terms: how can tragedy and suffering be rendered beautiful? And yet there remains the belief among certain moralizing schools of aesthetics that the beautiful art of tragedy is capable, through prolonged exposure, of anesthetizing the viewer to the pain of its subjects. It is ironic that Slavick would allow this myth such leeway, considering that her entire project is to a great degree devoted to an aesthetic process that gets erroneously labeled alternately as the aestheticization and the anesthetization of suffering.

The issue of Slavick's ambiguity toward these myths becomes clearer when we are made aware that it is through the eyes of Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, and Bertolt Brecht that the old admonishments of the aestheticization and anesthetization of suffering and tragedy seep into her discourse. In our resistance to let go of canonical texts, we signal that it is long past the time when our old warhorses of aesthetic criticism should be put to rest--if for no other reason than to clear room for more viable and vital voices to take hold. Benjamin, Adorno, and Brecht will always have much to tell us about the art and developing culture of the mid-twentieth century, as they had much to remind us between the 1960s and 1980s, when a new generation of political art cognoscenti were negotiating postmodernism. Yet not only have we since assimilated their more arcane insights with the art and criticism of our own day, but all three are to some extent being reduced to threadbare clichés in having their theories trotted out by every art writer seeking credibility by association with their precedents. All of which appears ironic when considering that as early as the late 1960s, student radicals in Europe, particularly in Frankfurt, came to regard theorists such as Adorno to be hopelessly out of date for their reticence toward taking political action (Leslie 1999).

In dwelling on aesthetic and political theories derived from the political events of the 1930s and 1940s, along with the then new development, spread, and application of photographic media, Slavick appears distracted from the vital issues of our own day. As for the myth of the beautified view of suffering, the myth is no more than the result of a misalignment of terms producing a disordering of the phenomenology of the simultaneous experience of beauty and politics in art. The dilemma facing artists isn't a matter of seeing to it that the viewer is or isn't anesthetized to suffering by beauty; it's a matter of the artist and viewer who refuse to look at ugliness and specifically at the ugly depiction of tragedy and suffering. The aesthete willfully turns away from the ugliness of suffering before art enters the equation and makes it so known by assuming the willful appellation of the "aesthete." The empathetic viewer, by contrast, is capable of seeing the political significance of an artwork despite whether it is beautiful or ugly. There is no anesthetization of the medium involved because the detachment of the apathetic viewer and the empathy of the compassionate viewer are both a priori to the art. What does harden us to tragedy and suffering is the sheer number of representations--beautiful and ugly--bombarding us daily. And against this barrage of journalistic depictions, a counterargument can be made that it is beauty in all its multivalent tropes that proves itself capable of drawing our attention back to the meaningful representations of human tragedy and suffering.

For whatever reason, Slavick doesn't come out in full support of empathy. Instead, she prefers to cite an array of antecedents and competing critical opinions that mull over the beauty versus empathy debate. Of course, in raising the very name empathy, the author cancels out the notion that the "beautiful view of suffering" is an anesthetic. We need only understand that empathy isn't a learned trait but rather is evidenced as early as infancy. Empathy enables us, as we mature, to form instantaneous judgments against cruelty, in favor of the generosity of others. And since empathy cannot proceed from nothing, the metaphors by which we express our capacity for empathy--that empathy is "in our blood," an innate component of "our collective unconscious," that we "inherit it genetically"--all convey that empathy is received through some innately human, and perhaps some higher animal, structural regeneration.

Whatever arguments we pick with Slavick over her rhetorical delivery, we must give her credit where it is due for focusing our attention on the generic and iconic manifestations of rubble as the premiere and ubiquitous signifiers of war. Not since the early 1950s, when Harold Rosenberg (1952) branded action painters as existentialist--their primal marks registering as political defiance and asserting their individual existence in the face of adversity and enmity--have we witnessed so acute a singling out of an artistic motif, in this case to represent the universality of war. Rubble is, of course, not just a metaphor for war; it is the direct material effect of war, and in the art that depicts or assimilates war, rubble is war's document and evidence. Rubble is the single assuredly universal and unifying principle providing continuity between present-day representations of war and the historic and prehistoric visual representations of battles known through art and archeology, even to the earliest human memories and recognitions of combat and ruin.

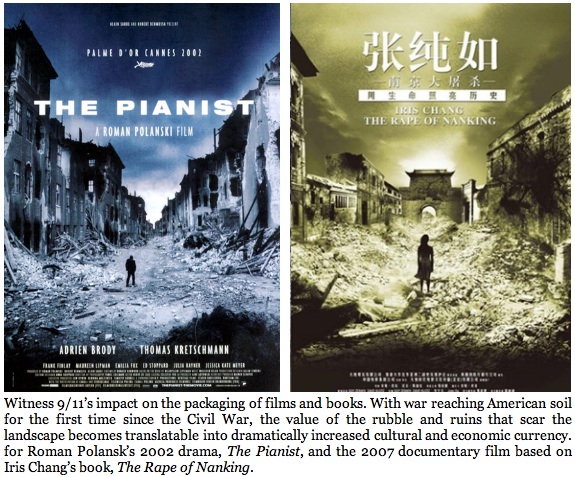

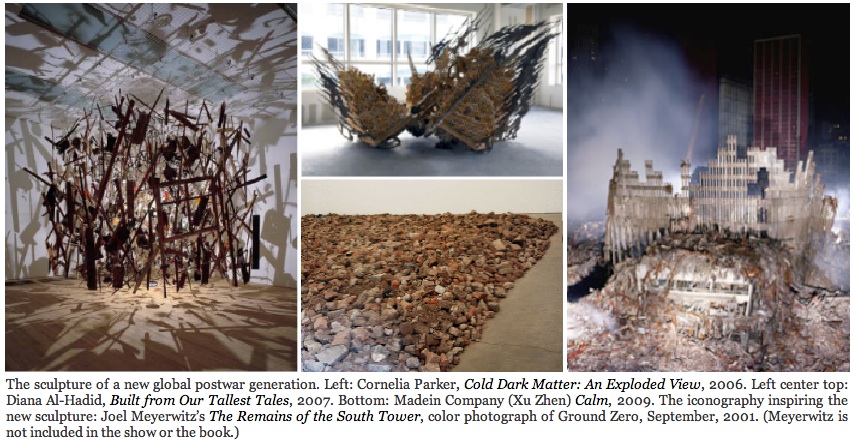

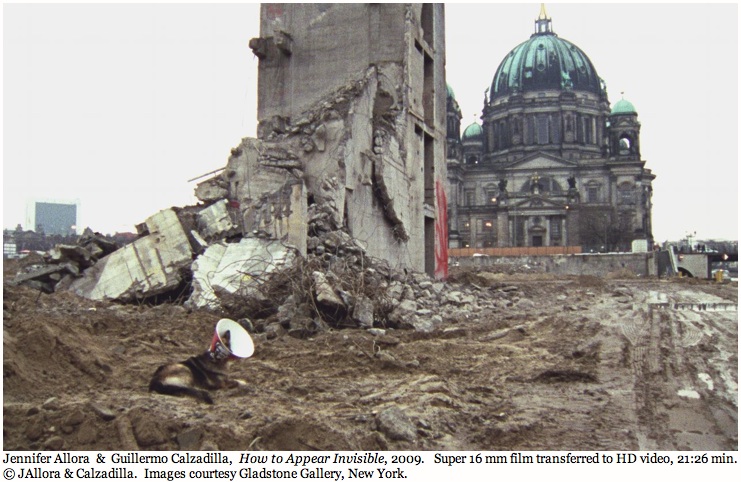

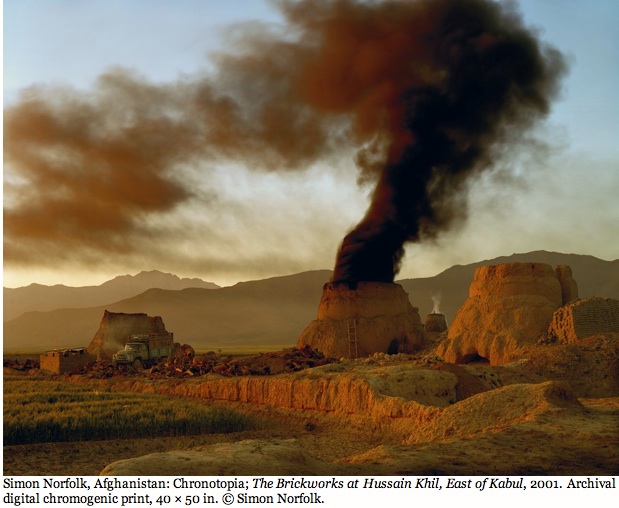

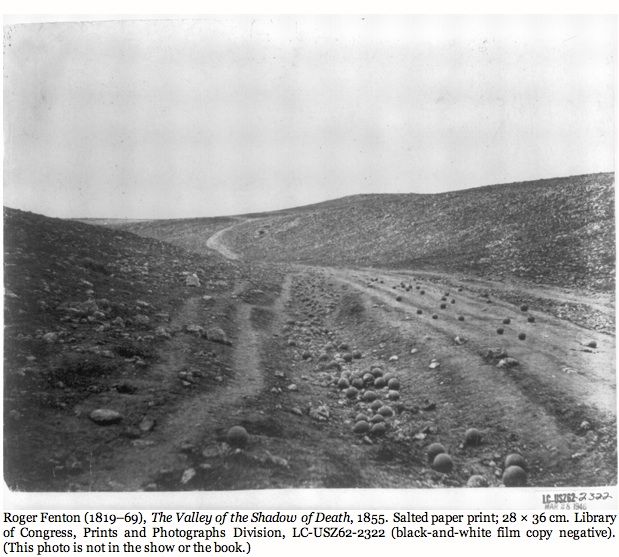

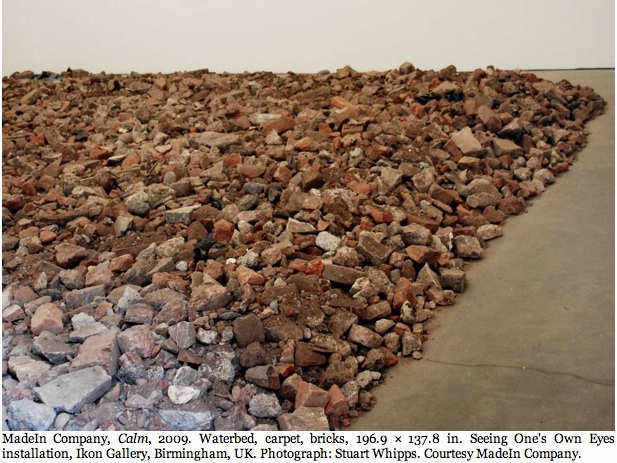

Hence this is not the first generation to incorporate rubble as the subject of the iconographic theater of war. Since the earliest war photographers were not able to record the motion of soldiers and their weaponry, after the remains of the dead and the convalescence of the wounded, the sedentary remains of fallen fortifications marking the abandoned battlefields are what characterize some of the more placid and picturesque nineteenth-century war photography. Among the earliest of these, Roger Fenton's Valley of the Shadow of Death, taken in 1855 during the Crimean War, has captured a dirt road in a ravine littered with cannonballs. Similarly, Interior View of Fort Sumter Showing Ruins, one of the many well-known photographs by anonymous Confederate photographers of the ruins of the South near the close of the American Civil War, demonstrates a remarkable continuity with the video (or stills) of Lida Abdul's White House, Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla's How to Appear Invisible, MadeIn Company's Calm, and many other works depicted in Slavick's book.

Despite the petty gripes we may have concerning her rhetoric, Slavick's nomadic selection process, and her choices in representing artists from myriad cultures, allows Out of Rubble to rise above and beyond this criticism. From the moment one opens the book, one is swept up by the powerful currents of cross-culturalism that flow through it. This is all the more interesting considering the number of artists that hail from nations once occupied by European powers. Taken together here, after decades of anti-Western postcolonial posturing, at last sharing the arena with their former colonizers, they transact, if not dictate, the terms of their own cultural interpretation. Given that the dominant art markets around the world, to say nothing of the traditionally polarized cultures they emerge from, still show steep resistance to the diversity and lineage of global multipolarity, Slavick's selection takes an elite, Westernized market to task--a market out of sync with the culturally diverse range of artists, who prove themselves repeatedly to be both activist and accessible to a wide range of audiences.

All of this makes one pause; it a curious thing that Slavick doesn't make more of the nomadic process required to produce global surveys of art such as Rubble, particularly given that the primary and unifying element of this nomadism is empathy. As for Slavick's curation, it is eminently open-ended, and it incorporates an array of aesthetics, genres, media, and production values. Realism, surrealism, existentialism, expressionism, minimalism, conceptualism, popularism--all the dominant models of the previous century stream through the film, video, sculpture, painting, photography, and installation art she has assembled here. This diversity is all the more admirable considering that the context and content of war is, by comparison, focused narrowly on relatively few motifs: the aftermath of the explosion/implosion, the ubiquitous and universal rubble, the survivors, the empathy felt for them, the location of the self amid the devastation, the question of "what next," the choice between more destruction or reconstruction. In the end, there is no one fixed political ideology manifested and no formula proffered for artistically depicting or embodying one. There are no revolutionary or utopian ends proclaimed, no strategies or tactics prescribed. Capitalism and government will not be rocked by this art; solutions to the world's conflicts will likely not be gleaned from it. And yet, much like the individualistic and highly subjective postwar art made under the canopy of existentialism between 1945 and 1965, there is a vital and resonant life force pulsing through the aesthetics of rubble.

Slavick's curation of a visual exhibition in a book succeeds to the extent that it should be recommended to any and all who both value a survey of politically motivated art and are searching for an art of renewed existential priorities. The reason that Slavick's nomadic selection works so well is that, besides the unifying principle of rubble that each work shares, the visual art assembled here presents interpretive and theoretical microcosms that are bound in forms we can accept as complete or, at the very least, sufficient to promote understanding. In each work of art, we are supplied with ample visual and contextual information to draw a meaningful model of some plausible reality. It doesn't matter whether the reality of the depiction is imaginary or real; what matters is that, bound by its own rules and structural framework, the art imparts all that we may require. In this respect, Slavick has curated a compelling array of art, successful as individual works and taken together to compose an overarching dialogue on the subject of the aftermath of war.

Slavick's discursive exegeses of texts, by contrast, is confounded and complicated by the brevity and dialectical succession of the textual snippets she provides. Before we can grasp at any one of the cursory handles to meaning extended by Slavick's citations, the handle is cut from us, preventing us from deriving any gratification from the citation before we are handed the next one and the next after it. If we at all sympathize with Slavick's Rolodex approach to skimming through cultural theory, it is because the idea of nomadically visiting the different, contrasting, even conflicting conceptual paradigms is a highly desirable method of comprehending the many facets of any given global conflict when afforded the opportunity to study its multipolarities in depth. Unfortunately, while we are provided an index of contemporary criticism of great value to the student who can use Slavick's book as an introduction to more in-depth criticism and commentary, in the cursory and elliptical format that Slavick has submitted, the coherence required to formulate a compelling argument for or against any given issue remains fugitive. We know that the clues are somewhere there to be found, but they pass us by too discreetly, too quickly, to be identified with any real assurance. To succeed resoundingly in her ambitious project, Slavick would have to compile a more comprehensive and thorough anthology of writings that are at least representative of each writer's reasonings.

However, in those portions of Slavick's essay when she relies on her own insights instead of deferring to a barrage of critical citations, or when she buttresses her chief points with passages of Wisława Szymborska's tone-setting poem The End and the Beginning, we begin to understand Slavick's motivation to produce a project that conceptually locates the detritus of war as corresponding with the observations of the artists. Slavick's vision especially translates into lucid and self-confident commentary when she concentrates on the artists' work, and it is these passages in the writing that shine. Yet, even here, she too often falls prey to the poststructuralist conceit of projecting the structure and tropes of texts onto the world--as when she refers repeatedly to the demolition and renewal of cities as "erased" and "overwritten." What is this but the symptom of an imbalance of idealist textual emersion, at the cost of a real perception of the world, which in this case deprives us of an appreciation of the collective manual labor and the years and billions of dollars it takes to level and rebuild war-torn cities?

It may be true that empathy can fill in the voids left by inexperience, but it must be an empathy that engages the perception of real events and living things--their sensations and affects in the world--not representations of them in language and art alone. The trouble is that a too-fussy preoccupation with language and structure that has seized hold of late poststructuralism to the point of making it unreliable as a recorder and analytic of observations makes us sacrifice facts for the self-important flourish of their expression. Slavick, who has an excellent command of the poststructuralist lexicon, too often falls into the traps that language and its cadence spring on us at the moment of our heightened seduction. The result is that too often the description of a sculpture or image becomes exaggerated, which causes us, in the distraction of poetics, to lose sight of the proportions of an event or a person in the world. If this sounds at all like the complaint that compels Plato to banish the poets from the Republic, this is indication of just how long we've been trying to balance the aesthetics and idealism that Slavick favors with the principles of representation and pragmatism that enable them to be shared with a wider and, in this case, political audience.

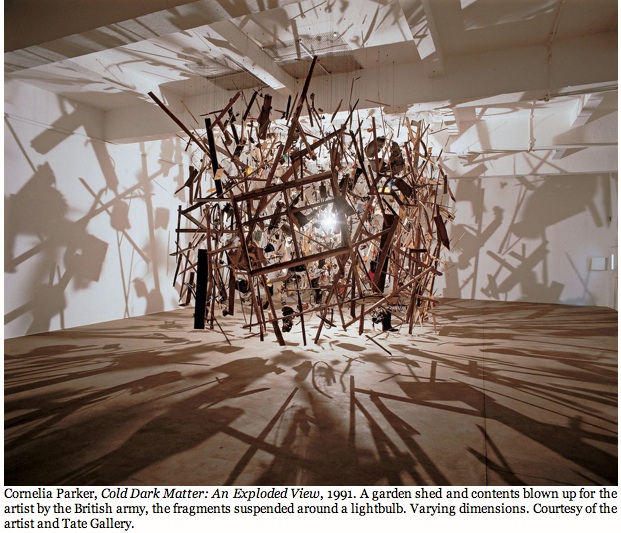

In addition to the artists already named in this review, Out of Rubble features the work of Joseph Beuys, Enrique Castrejon, Lenka Clayton, Helen de Main, Decolonizing Architecture, Jane Dixon, Christoph Draeger, Monica Haller, IDEA sarl, Andrew Ellis Johnson, Jennifer Karady, Mary Kelly, Anselm Kiefer, Barry Le Va, Curtis Mann, Raquel Maulwurf, Cornelia Parker, Thomas Ruff, Elin O'Hara Slavick, Susanne Slavick, Elaine Spatz-Rabinowitz, Pamela Wilson-Ryckman, and Tomoko Yoneda as well as an essay by Holly Edwards.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.