This is Part Five of the seven-part series, XX CHROMOSOCIAL: WOMEN ARTISTS CROSS THE HOMOSOCIAL DIVIDE. See Part One, Part Two, Part Three and Part Four on HUFFINGTON POST.

There is conjecture that men created art to become women. If this seems absurd, consider the following scenario.

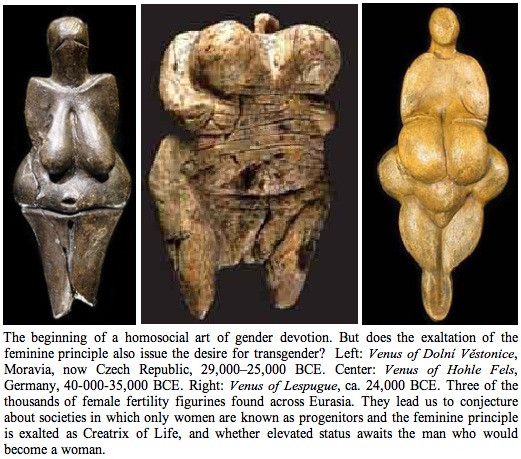

Imagine you are a man living amid the Paleolithic millennia, a time before men had conceived of paternity. Only women are ostensively seen bringing life into the world. Only women are exalted as progenitors bearing the life-giving principle and power. Men who have no ostensive role in regeneration are beneath women and are valued for their strength as hunters and laborers. But you happen to be an exceedingly ambitious man who wants to elevate your position. What would you be willing to do? Would you in mimicry of women's power fashion a form from the earth that resembled a human contour? Certainly that would bring you some celebration if you showed skill at its fashioning. Would you fashion a female form to show that you favor the female over the male? That would bring you favor from powerful women and deities. Would you do both these things while taking to dress as a woman? And if you were seeking great rewards from beyond the mortal realm, would you mutilate yourself, or submit to an order of mutilation, to become as much a woman as would be possible to you?

Before you say no to that last question, consider that the most recent statistics show that 1 in 30,000 males in America and Europe opt for sex-altering surgery each year, and that number reflects only those who will admit to the procedure. Consider also that castration has been in evidence for millennia, some of it as ritual ceremony (though not as widespread as the later custom of female genital mutilation) that contributes to the genesis of art.

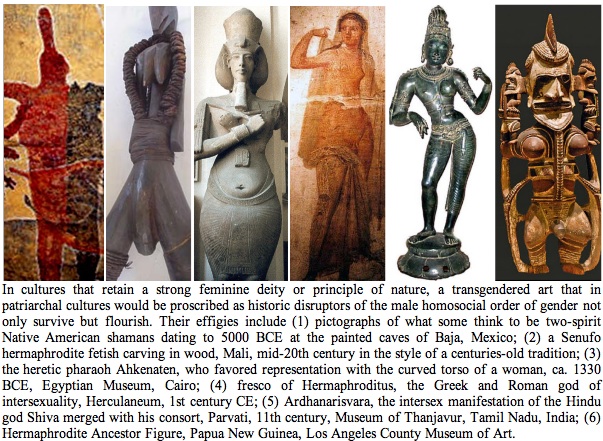

We know from the classical and tribal art of societies distributed across Europe, Asia, the Americas, Oceania, and Africa that transgendered individuals, many of them shamans, accumulated great esteem as leaders in both matriarchal and patriarchal societies. Art and written history together attest that people have long changed genders--or at least their gender significations--to attain power, just as they called upon transgendered spirits for protection, fertility, and healing. The world is still amply possessed of tribal societies that commemorate, if not practice, their legacy of shamanistic transgendering, just as they still produce the traditional art of transgendered "two-spirits" and hermaphrodites--even if only for the benefit of collectors and tourists. Considering that we know that art throughout its greater history mimicked, if not was made in effigy, of living things, it is not so far-fetched that the genesis of art may be found in the quest of men to magically invoke, to control, to produce simulations of life as a counterforce to women's ostensive monopoly on real life bearing.

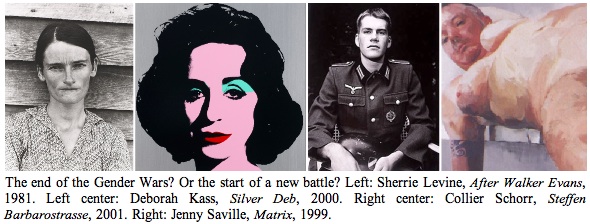

If I bring this hazy picture from an imagined prehistory into focus for a feature about contemporary women artists whose dissident art contributes to the redefinition of gender, it's only in part because three of these women have made an art of becoming men for the very point I am making here about the unilateral closures to the unfavored gender of the day and culture. For the most part, the discourse on the art of Sherrie Levine, Deborah Kass, Collier Schorr and Jenny Saville has been confined to the parameters of Western feminism and postmodernism. I see their art significantly transcending such confines--as more broadly bending the modern and Western notions of gender and transgender back to times and cultures that existed before the Judeo-Christian-Muslim models, which simplistically reduce the diversity of gender to two starkly "opposite" male and female principles and set them in stone. From this overarching perspective of art and politics, Levine, Kass, Schorr and Saville have made the re-signification of women and transgender of the last thirty years conversant directly with the art made anywhere between three thousand and thirty-thousand years ago--bracketing an artistic continuum within which we witness the evidence for the codes and signage of contemporary gender and sexuality as it evolved. It's an ongoing embodiment of art transcending its age and culture by imparting a knowledge that emboldens our activism--in this case the renegotiation of the codes, signage, and legislation that empower diversified gender.

Despite the archeological and anthropological backlash that "buried" the admittedly over-enthusiastic 1970s feminist theories purporting that a prehistoric matriarchal age dominated the Eurasian land mass, Paleolithic and Neolithic "Venus Figurines" found at the sites of ancient settlements from France to Siberia have never been discounted by hard evidence that women were revered for being benefactors of life, or that matriarchs held dominion over the klans at the sites where such artifacts were found. Nor has any evidence surfaced to conclusively dismiss the conjecture that until humans began to domesticate animals some ten-to-seven thousand years ago, many societies may not have conceived of paternity. Considering all these historical and cross-cultural factors, it no longer seems quite so absurd that, in an age in which only women can bestow life, that men possessed of the talent to make analogs of life would find it bewitchingly auspicious to become both an artist and a woman to elevate his status. Especially when in our own day and culture we have women such as Adrian Piper, Eleanor Antin, Sherrie Levine, Deborah Kass, Collier Schorr, and many more like them conceptually becoming men through their art.

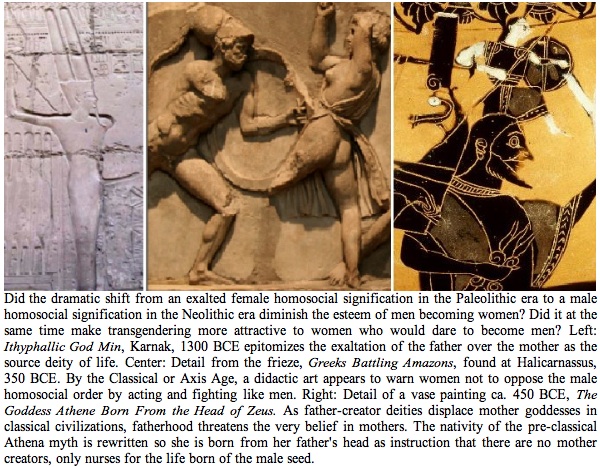

What we can show with the hard evidence of art--not small, scattered remains, but whole collections throughout Europe, Asia, and North Africa--is that the art made between the beginning of the Bronze Age and the end of the Iron Age (5000 to 330 BCE) indicates that female devotional figures increasingly become displaced by male figures. Finally, in the Classical Age (beginning roughly around 500 BCE), the feminine principle is demoted to secondary status or disappears altogether as male deities claim supremacy. In some cultures, such as Greece, and as dramatized in 458 BCE by Aeschylus in his masterpiece trilogy of plays composing The Oresteia, men go so far as to proclaim that there are no mothers, only feminine incubation vessels for nurturing the life-bestowing male seed. As Aeschylus wrote it: "Mark the truth of what I say! She who is called the child's mother is not its begetter, but the nurse of the newly sown conception. The begetter is the male, and she as a stranger for a stranger preserves the offspring, if no god blights its birth."

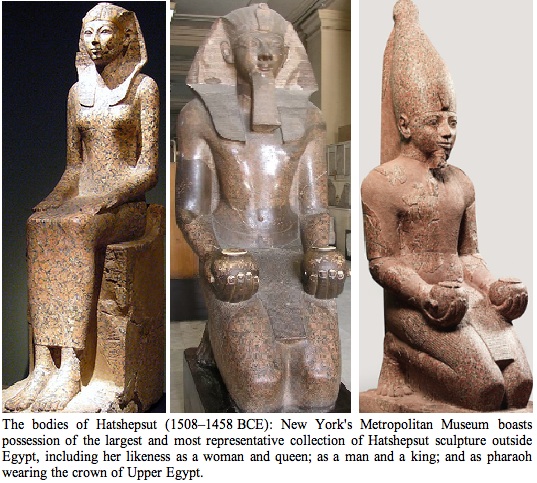

We need only look to the hard evidence of the portrait sculptures of Queen Hatshepsut, the 18th-dynasty pharaoh (1508-1458 BCE) who counts among the most powerful and culturally-significant rulers of Egypt, to find that transgendering now becomes a resort to reinforce and perpetuate a woman's reign. Egypt may have been slower than the other Mediterranean states to assimilate the encroaching paternalism. The Greek historian Herodotus is scandalized to find that Egyptian women work in trades and in markets. But given that the portrait sculptures of Hatshepsut had to be largely reassembled in the last century from fragments that were smashed and buried in pits by her male successors in an attempt to erase her memory, the art of Hatshepsut's reign and the ill-repute to which it fell after her death is indication of the dramatic shifts in the signification of power away from the feminine and to the masculine in the closing centuries of the Bronze Age. Certainly it is enough to compel Hatshepsut to have herself represented before her subjects as a flat-chested, broad-shouldered king wearing a false beard. As the first extant drag king in history, Hatshepsut is a bracket for the end of Neolithic woman worship, just as the art of women's crossdressing as men in the 19th and 20th centuries is the bracket announcing the end of male supremacy and the reprisal of women's access to power in modernity. I write this despite that the supremacy can be found to this date on the Metropolitan Museum's website, where it qualifies its unparalleled collection of Hatshepsut sculpture with this startlingly unreflective perpetuation of paternal prejudice: "For the ancient Egyptians, the ideal king was a young man in the prime of life. The physical reality was of less importance, so an old man, a baby, or even a woman who held the titles of pharaoh could be represented in this ideal form."

As to why contemporary women artists would pose as men, we need only consider that art made by women comes nowhere near the prices that art by men commands. At this writing the record price for a work by a living female artist is $6.2 million for Marlene Dumas' painting of female sex workers, The Visitor, sold at Sotheby's London in July 2008. Second is $5.1 million for Yoyoi Kusama's 1959 painting No. 2, sold in November 2008 at Christie's New York. Dumas overtook the $5.6 million record for a work by a woman artist alive or dead set by Frida Kahlo in 2006 until that amount was succeeded in June 2008 by the Russian Constructivist Natalia Goncarova at $8.9 million--currently the record for any woman artist in history. Dumas and Kusama are the only living female artists to join scores of living male artists commanding above $5 million, the most notable being Lucian Freud (then still alive) at $33.6 million, Jeff Koon's $23.6 million, Damien Hirst's $19.3 million, and Jasper Johns at $17.4 million. Beverly Pepper holds the next record for a living woman artist at $4 million.

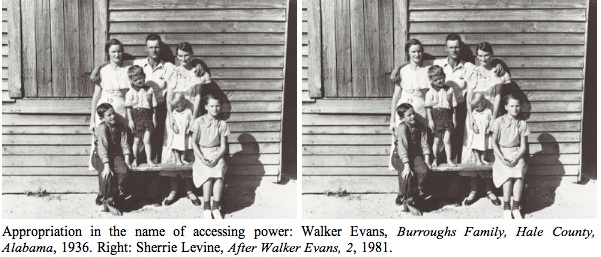

It should be noted that women, living or dead, were entirely absent from the high end of art sales prior to 2000. Of course, when Sherrie Levine intervenes on the brotherhood of artistic authorship in the early 1980s, the situation for women was significantly dimmer. It's small wonder that, with "the death of the author" rhetoric formulated by Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault still relatively new and celebrated, Levine would see in it a conceptual springboard for catapulting into the male arena--at least as a rhetorical and politically avant-garde spectacle. Despite the initial incredulity that greeted Levine's project of attaching her name in attribution to acknowledged replicas of celebrated works by Walker Evans, Alexander Rodchenko, Marcel Duchamp and other male masters, her challenge to paternal expressiveness, originality and creativity was ultimately made paradigmatic to a whole generation of feminist and transgendering art activists.

Although it would be another decade before the new language of presumed non-sexual homosocial attractions by Eve Kosofsky Sedwick and the fluid genders of Judith Butler entered the critical discourse to refine articulation of gender differentiation and its structures of support and opposition, Craig Owens in 1983 offered a suitably acute argument for Levine's project as "a refusal of the role of creator as 'father' of his work, of the paternal rights assigned to the author by law." Today we can see a broader picture: that Levine was doing more than challenging patriarchy and its paternalization of art markets and canons. She also significantly begins to destabilize the visual signage fortifying the homosocial gender divide. Every time the viewer looks upon Levine's work and mistakes it to be the authentic work of Evans, Rodchenko or Duchamp, Levine is virtually esteemed as, if not conceptually made, a man by virtue of misconception. But much more significantly, in destabilizing the assumption of gender of the author of an image or object, she also destabilizes the assumptions reinforcing gender identity.

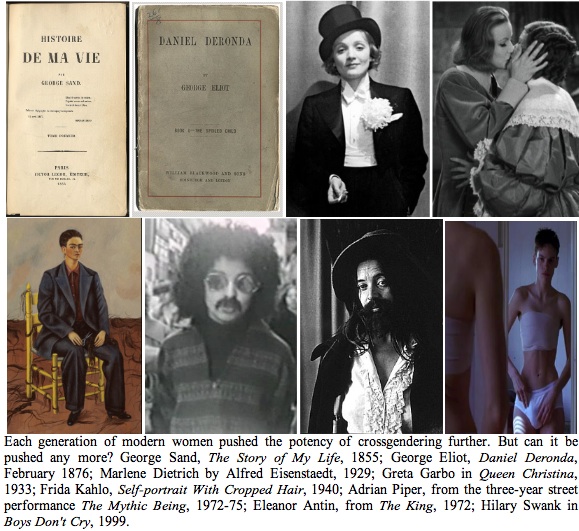

Levine, like Kass and Schorr after her, wasn't interested in making an art of crossdressing (though both Kass and Schorr have crossdressed at the outset of their deeper gender interventions). By 1981, crossdressing is no longer a potent tool for gender disorientation. This isn't meant as disparagement of the history of crossdressing. Certainly when crossdressing transported Aurore Dupin and Mary Ann Evans across the gender divide in the 19th century to make literary history with their male nom de plumes, George Sand and George Eliot, they gain real access to both publication and the vaunted literary canon. Similarly, crossdressing sets audiences ablaze for Marlene Dietrich's film debut in Morocco in 1930 and for Greta Garbo as the lesbian Queen Christina in 1933. Male dress politicizes Frida Kahlo's 1940 portrait in which she dons men's clothing and crops her hair after breaking off with Diego Rivera. But by the 1970s, despite that Adrian Piper's and Eleanor Antin's most memorable performance art entails them taking on male personas in discreet everyday settings in the world at large, crossdressing had become standard entertainment. It's not that crossdressing won't continue to have currency for its mapping of the homosocial codes of political and social difference. (Of course, if the gender divide is ever leveled, the very idea of "crossdressing" loses its points of reference.)

There is no doubt that authentic, real-life commitment to transsexualism remains personally and culturally vital and liberating regardless of its political force as stigma or ennoblement. And conventional, male-female transsexualism still plays an important part in raising consciousness about the politics and dangers of gender-conflation. The steep prejudice against transsexualism that often becomes dangerous and leads to tragedy tells us it does, as does a potent work of art reflecting that danger. Works such as Kimberly Peirce's film, Boys Don't Cry, in which Hillary Swank's Oscar-winning portrayal of the real Brandon Teena, a transgendered teen who was raped and murdered upon discovery that he was biologically female, will remain beacons of political activism and resistance for generating collective empathy for the tragic victims of hate crimes. But we should not count among the effects of Brandon Teena's tragic death, or others like him, as destabilizing the status quo's homosocial codes of gender, when in fact it is our code against cruelty and murder that is rattled.

The fact remains, with the kind of gender diversification now on the conceptual horizon, trading one conventional set of homosocial gender codes and signage for another can be seen to actually reinforce, not destabilize, the ancient, inherited homosocial codes, and the gender barrier separating them. The act of a man becoming a woman or a woman becoming a man is an act of crossing the homosocial divide, but it no less perpetuates the conventional premise that there are only two "opposite genders" corresponding to the two sexual chromosomes.

There is transsexualism that does erode, even helps to level the gender divide. Gender activists envision a mixing of many genders, perhaps as many genders as there are individuals. In other words, gender is the sum of the individual's subjective response to the biological body and its desires. In this respect, dismantling the homosocial divide means altogether disavowing the "bifurcation" and "opposition of genders." The experience of sexuality and gender doesn't truly exist at "opposite" poles just because there are two different sexual chromosomes and two different procreative organs. They are ubiquitously varied. Liberated gender and sexuality is holistic diversification that can't be measured because it is subjective. It's an ideological status, one of the mind, the personality--not an ostensive, physical, measurable fact. It allows a person to say "I am more than a woman/man," without stating further.

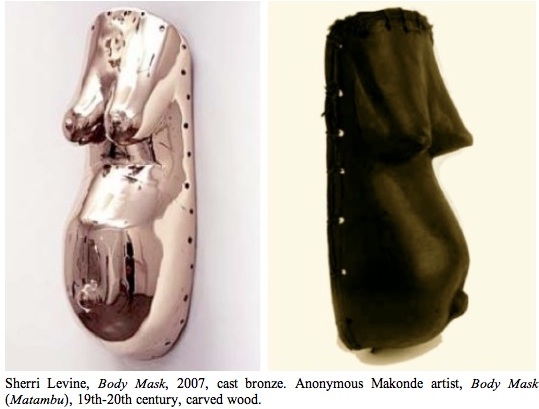

Levine gets at this kind of deeper meaning of gender with the 2007 sculpture, Body Mask. It's a work in which Levine realizes a greater amplitude of gender destabilization because she has this time seized upon an object representing an entire culture's exclusive male license for gender signification. The wooden body masks called Matambu that for centuries have been made by the Makonde men of Mozambique and Tanzania, represent the pregnant torsos of its nubile women. The body masks, along with accompanying head masks, called Lipko, featuring detailed women's faces marked by ritual scarification, are worn by boys in initiation rites of manhood. In selecting an art of gender masquerade--one intended to secure the parturient power of women to men--Levine's art becomes conversant with the art of the trangendering figures we find made in Neolithic societies around the world, especially those that have not yet been made cognizant of paternity. It helps to know that the Makonde are a matrilineal society in which women claim the strongest rule, are the primary producers of food and crops, possess title to the homes, and perpetuate the matrilineage. Anthropologists disagree as to what degree male envy of, and struggle with, the Makonde women's law contributed to the formation of secret male societies and rites in which the males carved and wore the female body and face masks.

What counts here is that Levine succeeds in drawing attention to the history in which the Makonde males adopted female gender codes intended to magically/psychologically/socially siphon off power from women's image and life-bestowing corporality for male use. In making her own literally and figuratively reflective body masks after those worn by the Makonde males, this time around Levine manages to destabilize the homosocial representation and its codes of gender even as she reclaims them for women's use. For no more than virginity can be restored after sex can the naive belief in an object's gender-specificity be reclaimed once that object's history of transgendering becomes memorable, especially when an object is as esteemed and collectable worldwide as are the Makonde body masks. When the Makonde men wore the masks they became women by masquerade. When Levine exhibits her body masks, she assumes not the gender of the Makonde men, but their privileged right to encode the body mask as an agent of disengendering--an object that despite its salient signification of parturition is, by association first with the Makonde men's masquerade and now in Levine's hands, made into an object detached from gender-specific reference.

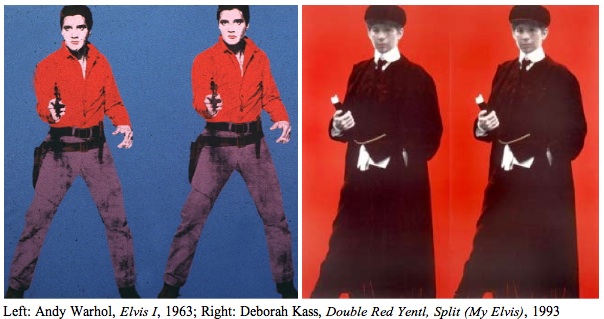

It is Deborah Kass who makes the leveling of the gender barrier a career-long enterprise. Although on the surface she appears to be, like Levine, primarily concerned with appropriating the artistic brands identifiable with modernist male icons, her art goes to greater lengths of diversification--the kind that composes individual experience. Kass' investment consists of much more than crossing the gender and sexual divide and seizing male codes and signage for women's use. She also imprints her lesbian and Jewish identity onto the appropriated male brand to forge a brand of her own making and temperament. With the new language of homosocial coding and fluid engendering at our disposal, we recognize that Kass illuminates the intricacies of homosocial valuation when she draws attention to more than just the gender and sexual orientation that made Andy Warhol's persona and art the star commodity it became. Seizing on Warhol's purposeful, yet stereotypical, queer devotion to, and desire to be like, celebrated women (Marilyn, Jackie, Liza), Kass turns a mirror-image of Warhol's art into a self-portrait by overlaying her own brand of ironic "stereotypes"--which is really to say she intervenes on Warhol with her own take on the mythology of the lesbian mimicry of, and identification with, men and all things male. In this case, it is famous male artists and their signature art brands. The complexity of Kass's psychological and sociological crossing and appropriation of conventional male signage is heightened when she interjects the signage of ethnic stereotypes into the mesh. We see this most effectively in Kass's Double Red Yentl, Split (My Elvis), whereby Warhol's worship of Elvis Presley is transposed with her own devotional image of Barbara Streisand in male Yeshiva drag (from Streisand's film Yentl), what amounts to Kass inserting Jewish lesbian chutzpah into the space of what graphically amounts to have been Warhol's gay-male swoon. That the beloved objects of both Warhol's and Kass's desires are presumably heterosexual further complicates the gender and sexual codings being unknotted and laid out for all to consider as the widespread and wholly normal, if problematic, phenomena they are.

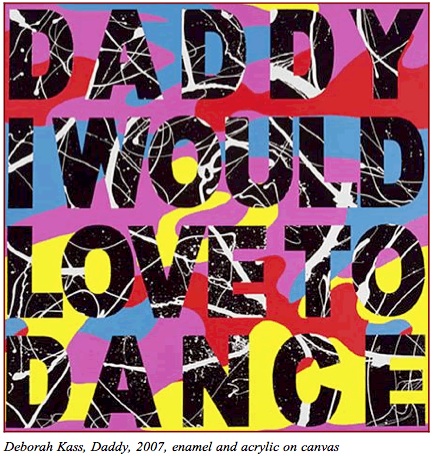

One might have expected Kass to next commodify the gender desire she has in common with the hetero-male populace by seizing hold of hetero-male sexual iconography and making it assertively lesbian in the manner of Lisa Yuskavage (see Part 3). Instead, Kass levels the divide another cubit down by further deflating the modernist myths of formal and aesthetic detachment that kept the issue of sexual politics conveniently at bay from the male artists' iconography during the heyday of their careers. Ironically, it was the male modernists' formalist proscription of sexual politics in art that ignited feminist art to begin with, and Kass pays acerbic tribute to the leveling of high and popular patriarchal myths that the feminist critique realized by making the male iconography shine throughout the process of its deflation. That she succeeds is in large part due to her sense of humor. But it's not just any humor. Kass taps into the legacy of the self-deprecating American-Jewish standup comedian. When compounded into the triple-whammy of woman, Jew, and lesbian, Kass has assembled all the material she needs for a routine that blasts away at the homosocial and eurocentric foundations exalting the heroic hetero-male modernist above the rest of the world's cultural production. As if she hadn't enough axes of difference to cross (or enough political axes to grind), Kass reaches for the bittersweet lyrics of pop songs and show tunes written by men about women, or for women to sing, to overlay her renderings of the art fathers with bitingly ironic recontextualization.

The result is a kind of conceptual crossdressing to end all need for crossdressing. Again the ingenuity is in the complicated mix that makes it near impossible to determine when it is a man and when it is a woman being signified and signifying. We may first fixate on a macho-existentialist Jackson Pollock painted surface, because it is iconic. But then we are pulled into its overlay of tres-gay Warholian camouflage stenciling spelling out the pining lyric from Chorus Line, "Daddy I Would Love To Dance." Another work recalling Ad Reinhardt's minimalist black-on-black paintings sings out Rick James's "Super Freak" ("She's a super freak, super freak, she's super freaky. Oh-oh-oh-oh-oh-oh-oh-oh-oh."). Kass's paintings are a veritable shooting range crisscrossed with targets--heroic male painters (Stella, Guston, Noland); popular hetero-male fetishizations of women as weak-kneed submissives ("Daddy") and insatiable ho's ("Super Freak")--all shot through with Kass's imitable humor. We have yet to see if the homosocial divide can be eroded away by laughter, but in that we do (at least in the art world) recognize and laugh at the large-than-life myths and icons of male homosociety being shot down, Kass helps contribute to a vision that the homosocial divide isn't the omnipotent obstacle it used to be, and likely to be even less so a decade from now.

Most importantly, in terms of dismantling the homosocial divide, Kass undertakes the dismantling entirely within the aesthetic and cultural constructs that the male homosocial art enclaves defined. If she weren't obliterating the male homosocial cultural mythos so unrelentingly, we might have said that Kass achieves the dismantling of the artworld divide by becoming a man by definition of assuming the male prerogative to redefine aesthetic and cultural codes in ways proscribed to women just a few decades ago. The achievement, however, is that in seizing the prerogative, Kass, like Levine and Schorr, makes such a distinction untenable by stripping--or really diversifying--its gender association beforehand. In its place we see the making of a specific splicing of the new world diversification of gender that so far has no name. Anyone up to the challenge of unwinding it all for the sake of reflection may find that the situation of our present inarticulation on a subject of diverse engendering will one day be replaced by a lexicon of genders, the way that Inuits have a lexicon for different categories of snow. For now it sounds like a bland stand up joke without a punchline: "What do you call a lesbian, crossed with a straight man, crossed with a faggot, crossed with a feminist, crossed with a homophobe, crossed with a motherf..."

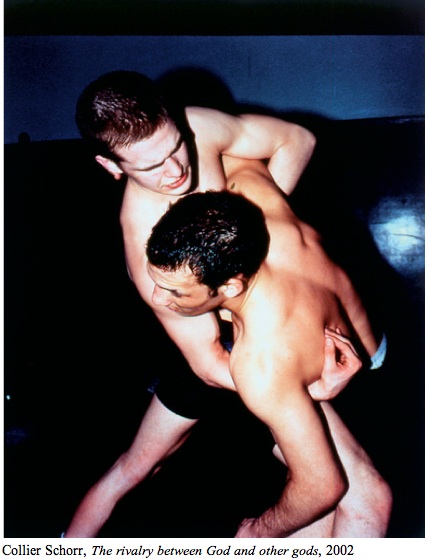

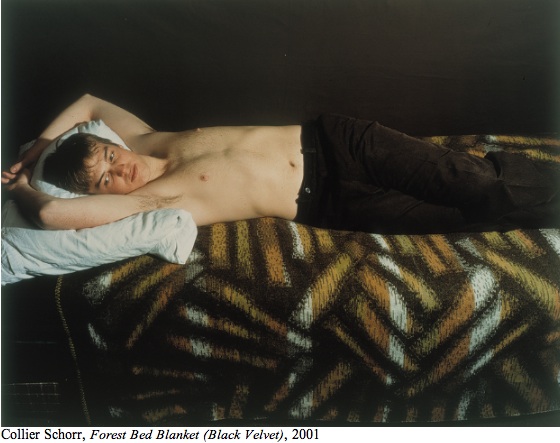

In tangent to Levine and Kass, Collier Schorr's early photographic series of "faggot photography" delves what may be furthest within the discourse of gender destabilization by route of empathy. Schorr's art is based entirely on the dubitable presumption that she can visually effect the experience of gay men by spending prolonged periods conceptualizing herself as a gay male photographer collecting and exhibiting portraits of attractive youths he encounters in gymnasiums, at gatherings, on the street, and so forth. Schorr's project follows the artworld precedent established by Eleanor Antin's 1972 performance art, The King, and Adrian Piper's 1972-1975 ongoing performance The Mythical Being, and the surviving photo and filmed documentation, which consist of the artists assuming the persona of men confronting stereotypes of gender, and in Piper's case, of race.

Yet, there's a world of difference between these two bodies of work and Collier Schorr's project of transgendered subjective phenomenology that reflects the intervening quarter-century. Neither Antin's nor Piper's work draws us inside the male experience of desire to the degree that Schorr's work does. We don't see what their "he" sees, the way that we see what Schorr's queer male persona "sees." Antin and Piper present their characters externally--keeping the viewer at a distance with the conventional Fourth Wall of the performer-audience interface. Schor, on the other hand, shows us not herself in drag, but the objects of desire "he" photographs, which allows us to form our own picture of the man whose experience we enter. It's an ingeniously interactive hook that keeps us engaged. Whereas Antin's and Piper's visual presence--their assumed identities placed front and center and showing through the masquerade--compels us to return to the real-life identification of a woman crossdressing, Schorr's invisibility sustains the analogy of a man photographing the young men he desires. Another way of putting it is that Schorr transubstantiates the physical act of crossdressing into a simulation of cross-desiring not unlike that we experience in the virtual world of avatars, the difference being that we as viewers see through the eyes of the avatar, rather than see the avatar itself.

In the end, the depths of phenomenal and psychological maleness and male desire that Schorr conveys is withheld from Antin and Piper because the latter by all appearances neither attempt to desire what the male persona she assumes is claiming to desire, nor does she show us his desire (though Piper does write it out for us in her photo documents--which is a cognitive, not a phenomenal, sharing). None of this is meant as disparagement of Antin or Piper, artist I've long admired, and in fact the comparison is uneven because Antin and Piper are working firmly within the homosocial boundaries of feminism--a hurtle of its own--while Schorr, with the feminist hurtles of Antin and Piper behind her, can concentrate not only on crossing the homosocial boundary, but on breaking it down to traverse as far inside the experience of the male-male desire as is possible given the interfaces of bodies and minds.

Schorr's project is also noteworthy for entering the debate over the nature of experience and desire waged throughout the last century between the schools of psychology and phenomenology--specifically in terms of whether experience is exclusively singular or can be shared through language such as art. By suggesting the interface between the private individual and the public society is porous and passable and then making the interface central to the political and aesthetic discourse of sexuality and gender difference, Schorr renders porous and passable the divide that historically closed passages between genders off while enforcing women to have one kind of experience and men another, a difference that becomes compounded with each little sexual and physical difference raised. In this light, Schorr's homosocial crossover to the gay male experience raises the question: if both the individual's desire and the individual's relationship to the art object are subjective, how then can the codes prescribed by society and relayed through art presume to establish and perpetuate boundaries for only two types of gender? And with each having a choice of only two types of sexual desire? The logical alternative, yet an alternative as well based on the empirical range of human difference, holds that gender and sexuality no longer be premised on only two categories of genital anatomy, but by an unbounded continuum of human experience that contributes to the formation of myriad desires.

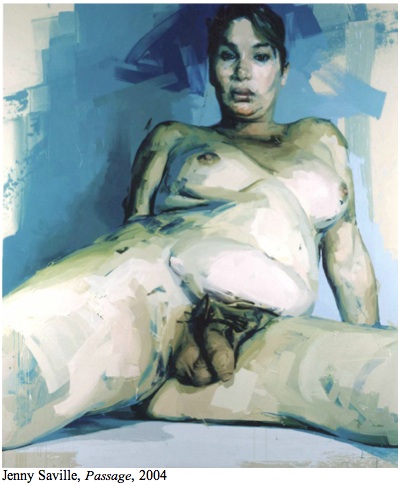

The conceptual models of Levine, Kass, and Schorr indicate that we don't require sex alteration surgery, hormonal therapy, or crossdressing to change our gender-orientation or to acquire the privileges enjoyed by the dominant gender. But as modern economies and technologies afford us the stability and ability required to change our anatomy at will, we find ourselves with imagery of a more blatant destabilization of gender and erosion of the homosocial divide. In this regard, it is Jenny Saville's painting Passage that provides the most graphic and radical leveling of the gender divide. Its subject is far from shocking to anyone who has ever walked inside a porn shop, where explicit depictions of transsexuals make it clear that the modern individuation of gender is available to 21st-century residents on demand.

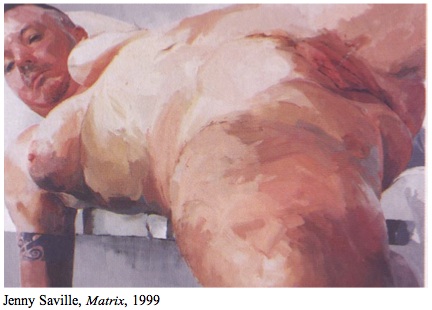

Saville has explained the circumstances of her sitter. "With the transvestite [painting, Passage, 2004], I was searching for a body that was between genders. I had explored that idea a little in Matrix [1999]. The idea of floating gender that is not fixed. The transvestite I worked with has a natural penis and false silicone breasts. Thirty or forty years ago this body couldn't have existed and I was looking for a kind of contemporary architecture of the body. I wanted to paint a visual passage through gender--a sort of gender landscape. To scale from the penis, across a stomach to the breasts, and finally the head."

Like most of us, Saville was at that moment in 2004 awkward in her articulation of the incipient gender passage she is groping to define, to say nothing of seeming blithely removed from the political morass that she is stirring with her painting. Although she confuses a transvestite, who is no more than a crossdresser, with a transsexual, who undergoes surgical implantation or removal of genitalia, by sight of Passage alone, it is unclear to the viewer whether or not her subject is a transsexual or an intersex--someone born with some formation of both conventionally biological male and female organs, and which from antiquity was called an hermaphrodite in the West. Yet, even if we regard Saville's painted subject as a transsexual, we're given no indication whether the subject has arrived at some final and satiating stage of surgical transsexuality, or if s/he will complete the process of becoming conventionally-biologically male or female.

Without knowledge of Saville's explanation, it is a measure of the times that Passage could register equally well for the viewer as an intersex or a transsexual. What is important is that Saville is fully aware that in representing a living conflation of gender duality arrived at either by birth or by choice, she is effecting the most radical destabilization of homosocialism and gender dualism imaginable on a variety of counts. In Western art, the intersex is a subject not much visited in art since the Classical Age. But as previously stated, artistic hermaphrodism still lives on in the traditional art of Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Mali, and New Guinea. Apart from the hermaphrodite's function as an ancient and positive marker of gender diversity, it takes our modern and disparaging notion of the circus freak to task while asking how and why we became so grossly at variance with the reverent tribal (African, Oceanic, Native American) and classical (Greek, Roman, Nordic, and Indian) significations of hermaphrodites as divine incarnations, shamans and oracles, all bestowed for the benefit of humans and to be esteemed and followed, if not worshipped. Of course, to understand the motif and history of the hermaphrodite is requisite for understanding the formation of homosociety. For it is in understanding that postclassical religions and their artists made these innocent children of nature into monstrosities that we also become aware of how dangerous hermaphroditic imagery had become to the ascendant male homosocial order for retaining within it the once enshrining, "sacred feminine" signage that had to be contained to enforce the emerging sexual and moral order.

If we are left disoriented by the loss of fixed genders as a basis for identity, it is because humankind has for so long adhered to bifurcated prescriptions and proscriptions of gender. In this context, Sherri Levine, Deborah Kass, Collier Schorr, and Jenny Saville can be seen as jointly making art that implies the true disruptors of the homosocial divide aren't feminists or queers (who comprise their own homosocieties), not even transvestites and transsexuals (who inadvertently reinforce conventional gender boundaries), but individuals--potentially any and all of us who should for any reason choose to abjure gender identity locked to anatomy or DNA, even if we prefer to remain identified (in mind or appearance) by the gender codes that have been handed down to us.

The four artists compel us to speculate on the variety of significations that is possible in a culture that detaches from the conventional view that gender is defined by desire, not by biological organs, or XX and XY chromosomes, or cultural structures built on and around either of these constructs. As desire is unspecific and unbounded, so is gender. For that matter, gender becomes redefined as the gestalt of personal desires--not just desires for genitalia and anatomy, but as well for kinds of clothing; face and body hair; fetishes; imagery; lifestyles; social imagery, kinds of familial relations, preference for dominance or submission--desires that in their mix of human circuitry vary indeterminately and numerously with, and likely equaling, the sum of individuals in the world. In redefining gender by individual desire, the homosocial divide is leveled and its components dispersed in one fell swoop. Or so it goes in the utopian dreamwork of transgender.

It sounds wildly idealistic when the personal desire to individuate and diversify gender is blown up into a social system. But the model of individuated gender is really no more than the logical outcome of speculation on the parameters of one's own desire in relationship to the desire of others. It simply breaks down to a matter of most of us not knowing how different we are when defined by our desires because there is so little articulation and comparison of individual difference by desire except when it is expressed in limiting terms of opposing, dual categories of male and female, hetero- and homosexualities, which is hardly articulation of our individual differences at all.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.