Jack Goldstein × 10,000, the first American retrospective of the seminal Pictures artist, appeared this summer at The Jewish Museum in New York, May 10 - September 29, 2013. Gretchen Bender: Tracking the Thrill, presented key multichannel video installations and single-channel videos at The Kitchen, August 27 - October 5, 2013. See more at The Jewish Museum and The Kitchen websites.

The confluence in New York this summer of two exhibitions by Pictures Artists, Jack Goldstein (1945 - 2003) at The Jewish Museum and Gretchen Bender (1951-2004) at The Kitchen, supplied the more theoretically-minded art cognoscenti an art historical quandary to ponder. Does the neglect of Goldstein and Bender as artists over the last two to three decades tell us something more comprehensive about the Pictures Generation as a whole? Did the Pictures Artists, perhaps, by virtue of serving as a reflexive bridge between the art world and the media mainstream, only serve to open the doors of late 20th-century art to a more protean generation of artists to come after them? With their eyes and lenses focused emphatically on appropriation, did they render themselves obsolete by counting themselves ideologically out of the renaissance of non-reflexive picture making about the world at large that ensues today?

The questions are more than academic. With the Goldstein and Bender shows, along with last year's MoMA Cindy Sherman retrospective, following on the heels of the Metropolitan Museum's 2009 exhibition, The Pictures Generation, 1974-1984, the 2013 installations attempt to posthumously reassess the careers of two of the Pictures Artists who had largely gone neglected over the past two decades. On the one hand, the shows supply a focus lost in the Met's show, largely because the inclusion was too-generously inclusive. Comprised of thirty-one artists--John Baldessari, Ericka Beckman, Dara Birnbaum, Barbara Bloom, Eric Bogosian, Glenn Branca, Troy Brauntuch, James Casebere, Sarah Charlesworth, Rhys Chatham, Charles Clough, Nancy Dwyer, Jack Goldstein, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Thomas Lawson, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, Allan McCollum, Paul McMahon, MICA-TV (Carole Ann Klonarides & Michael Owen), Matt Mullican, Richard Prince, David Salle, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, Michael Smith, James Welling, and Michael Zwack--the Met's associate curator of photography, Douglas Eklund, oversaturated the potency of the original movement by including artists who veered either too much toward making actual content art or keeping to more formal concerns.

Barbara Kruger's explicitly politicized commentary and appropriations, Eric Bogosian's and Michael Smith's performance art, and MICA-TV's docu-videos, all discursively sojourned well outside the boundaries set down by the more reflexive and apolitical content of the original Pictures Artists, while Glenn Branca's minimalist guitar jams and Charles Clough's photo-emersion paintings harken more to a blending of formalist structure with expressionist abandon, than to pictorial reflections.

If Gretchen Bender was left out of the Met's show, it is no doubt because she came late to the movement and died prematurely--though she better fit the Pictures bill both structurally and ideologically than numerous other artists included in the Met's show. Her work also has had a more pervasive audience when considering the music videos she produced with her then-partner and director, Robert Longo. Her absence from the Met show was an oversight that The Kitchen's Tim Griffin and Lumi Tan can be seen correcting with the help of organizing curator Philip Vanderhyden.

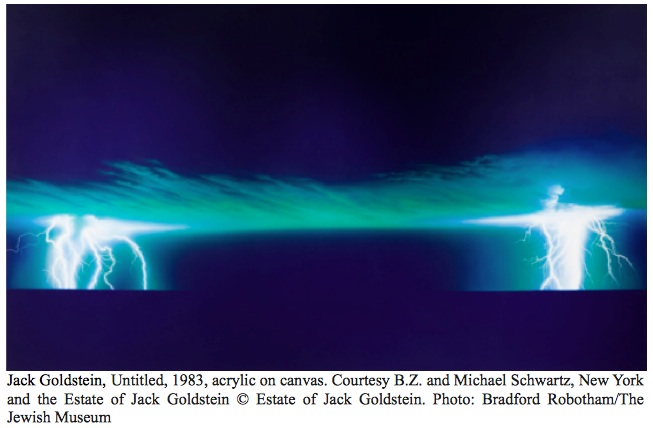

Goldstein, on the other hand, though long recognized as among the first of the Pictures Artists, had retired from art making and lost currency in the 1980s art market after a series of highly stylized but commercially evocative airbrushed paintings made by a team of assistants failed to impact on art audiences. The appraisal of Goldstein's career was dimmed even more after his addiction to drugs, and finally the taking of his own life in 2003, negated any headway the artist and his supporters made in reviving his career. But things have brightened somewhat for Goldstein's legacy since the Met show, especially after The Jewish Museum's director, Claudia Gould, and Assistant curator Joanna Montoya, came to the rescue in providing anchorage for a show of Goldstein's most impressive work put together by guest curator Philipp Kaiser. Gould was, after all, an intern at New York's Artist Space in the early 1980s--the alternative art center that had birthed and nurtured the Pictures movement with a 1977 exhibition that was accompanied by the seminal catalogue essay defining the movement as written by critic Douglas Crimp.

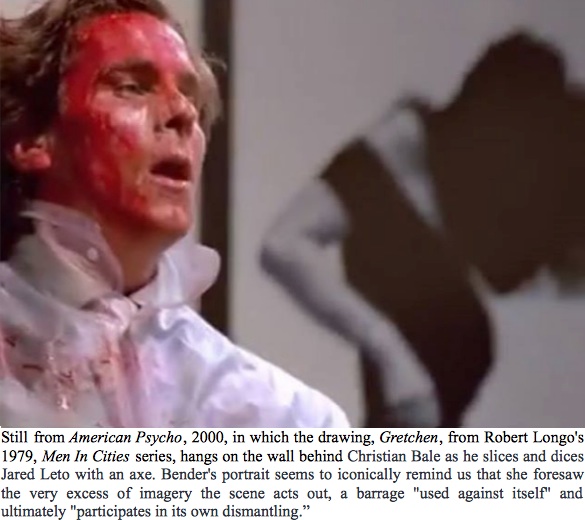

The Goldstein and Bender shows, both in terms of their strengths and their weaknesses, remain of interest chiefly because the two artists, like the majority of the original Pictures Artists, partook in a Janus-faced bridging of the formalist century of the past with the contextually diverse art world that would become their future--our present. The shows' weaknesses can only in part be explained by the small body of signature work that survives them. Their work also invites scrutiny because both largely derive their ideas and processes from more significantly visionary, protean and, most importantly, iconic artists. Sadly, as both Goldstein and Bender approached death, each showed signs that s/he might have gone on to contribute significantly to the digital mix we came to call New Media art that only began to find its stride with a generation half the age of the Pictures Artists. The most damning blow to their legacies, however, is the sad fact that neither artist left us a sufficient body of historically documented work to fortify their achievements as artists who contributed significantly to the analysis of the pictorial codification that the mainstream media, advertising and entertainment industries disseminate to reshape cultural and political thinking. While their art, like most of the Pictures Artists, was tautologically focused inward by referring chiefly to the processes of picture making, a younger generation came to make pictorial art telling us more relevant, and often more insidiously dangerous, things about the way that corporate and institutional media have reshaped the world.

Ultimately the Goldstein and Bender shows prompt us to ask whether in retrospect the Pictures Artists were really no more than a means to an end that would have come with or without them. That end being the art world's shedding of its centuries-old successions of linearly dialectical, but contesting, movements, with each successive generation attempting to supplant the last. The Pictures Artists seem to have hastened the art world's reinvention, though they had little to do with what it became by the 1990s--a nomadically and globally diverse panoply of new and old media set on redefining art not along opposing lines of content and form, history and the avant-garde, but with infinitely capacious and multifaceted contextualization of the full range of difference that coincides without any one movement, media, or issue claiming dominance of the art markets and discourse.

In their way, the Picture Artists inhabited a rarefied terrarium. While most the world held pictures to be so plentiful as to be not worth more than momentary regard, and while the affluent elites put historically celebrated pictures--mostly painted, but increasingly photographic--economically outside the reach of the average art collector, the Western avant-garde of the Conceptualist 1970s had shunned conventional picture making in drawing and painting, while relegating picture making to documentation, a role secondary to the structures, processes, and intentions that artists of the day were presenting as Conceptual Art. In this context, Pictures was conceived of, however intuitively or theoretically, as a critique of the mediumistic signification of models of reality--a critique premised on the view that the models of reality are interchangeable and disposable, and as such are secondary to the more essential and universal process of representation and signification itself. What the picture signified wasn't important. Just the act of signification was to be esteemed.

We shouldn't forget that except for the theories of psychoanalysis (largely Freudian and Jungian) and iconography (deriving from Panofsky), the larger discussions of pictorial art circulating in the 20th century, even relatively after the introduction of Pop Art, was void of articulated principles regarding the economic and political codings invested in pictorialism and figuration--at least compared to the hyper-developed formalist and structuralist principles that were advanced between 1900 and 1970. As a result, much of the early criticism that greeted Pop Art in the 1960s did not hail the movement for its critical distancing from traditional picture making in favor of augmenting an emerging perspective on rampant consumerism cued by media conditioning--as we do today. Instead, Pop Art was initially celebrated for what was perceived as its welcome revival of a school of figuration reflecting the social environment that at last would deliver Western civilization from a half-century of domineering abstraction.

It is little wonder that when critic Douglas Crimp collected a retinue of artists who made pictures not to tell us something about the world outside of picture making, but to reflect the cultural processes and codifications invested in all picture making itself, he described not just the 1970s generation that both reacted to and retained some measure of the Modernist proclivity for tautological endgames--of making art reflecting its own media and cognitive processes--he also discreetly reaffirmed a relatively new appraisal of the Pop Artists as critics of consumerism and the media. Whether we regard Pictures as a critical or a marketable restraint on artistic practice in 1977, the year of the now celebrated Pictures exhibition held at Artists Space, Crimp and the Pictures Artists he represented were not ready to discuss the revival of picture making as vehicles delivering the content of the world apart from art. The pictures of the Picture Artists conveyed only information about how pictures codify what information we derive from them, with all other interpretations a secondary, if not arbitrary projection of the viewer.

In essence, Crimp's discussion of pictures really didn't introduce a new phase of aesthetic or cultural growth. It provided a new context with which artists could reintroduce the visual structures required at the end of the formalist century to reinvigorate the material and visual structures, processes and materials that build up into iconography and its content--in this case a content so minimal and reflexive, at times even tautological, that it was essentially no more than a formalism describing the performance of making pictures. "Performance" here is a reference back to the Performance Artists who tie the Pictures Artists to the minimalist and conceptualist modes of art making preceding them. In this light, we should remember that Performance Art sought to restore the body as a vital site and vehicle for an art of protest against the formalists who had for a half century virtually denied the body its due acknowledgement. But whether Crimp had foreseen it or not, he was also opening an outlet for a century of pent-up frustration among non-formalist artists yearning to revitalize an art of content from the days since abstraction had stolen away the international attention some seventy years before. In this regard, Pictures theory from the start was a hyper-theoretical offshoot of Pop Art, crossed with Minimalist Art, Conceptual Art and Performance Art--a hybrid that capitalized on all the semiotic afterthoughts about visual media that grew out of, and retroactively was used to articulate and critique, the advertising and media empires that Western art forms mirrored in the late 20th century.

It helped that Pictures Art appeared just as critics were eager to put to use the semiotics theory being retrieved by academics from the decades-earlier publications of Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Sanders Peirce, along with the more recent structuralism of Roland Barthes, the media analysis of Marshal McLuhan, and ultimately the Deconstruction theories of Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man--all grafted onto the politicized lectures of The Frankfurt School, particularly the critics Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse.

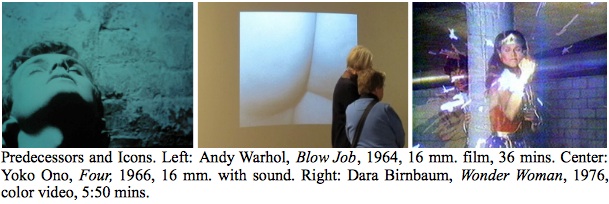

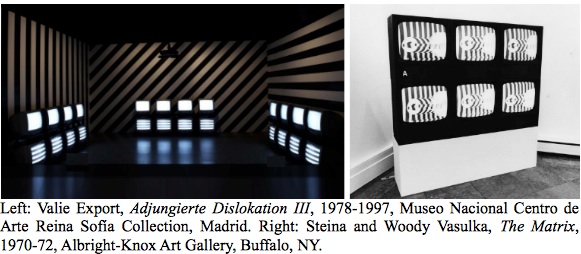

From their leads, Crimp and the critics admiring him, premised Pictures theory on structuralist, poststructuralist, and critical strategies that the Pop Artists only, yet brilliantly, intuited. But the Pictures artists not only had the advantage of being privy to what came to be collectively called Postmodernist theory to hone their own pictorial reflexes. They also owed their artistic strategies to the reductive and repetitive visual and temporal media and brand mimickry of Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist and Claes Oldenburg; the gestalt formulations of the Minimalist artists Carl Andre and Donald Judd; the cinematic-narrative reflexivity of Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, Alain Resnais, Ingmar Bergman and Rainer Werner Fassbinder; the scrutiny of media attended by the Structuralist avant-garde filmmakers, Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits, Yoko Ono and Yvonne Rainer; and the video explorations of Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, Joan Jonas and Woody and Steina Vasulka (the latter being the husband and wife artists who founded The Kitchen). These are the historically lauded visionaries whose contributions defined the formal vocabularies specific to the new media images favored by the Pictures artists, especially those of computer-generated film and video. If the majority of Pictures Artists don't loom as large in art history as these earlier generations, it is because they derive so much, both formally and ideologically, from them.

Keeping this collective debt in mind, the coincidence of the Goldstein and Bender shows, and the curators' attempts to revitalize the work of two artists too long neglected, prompts us to ask whether the Pictures Artists as a whole are to be historically valued more for the pathway they pried opened through the formidable wall of Modernist formalism--a wall that had for decades closed off the art world to artists who worked in figurative and pictorial modes--than they are to be esteemed for what their work on its own has to say to us today. The question becomes increasingly relative as we consider--with the sustained popularity of Cindy Sherman notwithstanding--how much more acclaim and sustained market value has been heaped on subsequent generations of image makers who have proven themselves to be more protean as artists aesthetically, conceptually, semiotically and politically.

The derivations operative in the work of Goldstein and Bender prompt us to consider how much the Pictures Artists reflect more brilliantly original contributions made by artists working a decade and more before them, while leading us to a dead end of 20th-century visual theory that relies on tautological practices, systems, iconographic codes and valuations of materials. The Pictures Artists, after all, compose the last generation of artists to feel the urgent need to concern themselves with making art that reflects back on how art functions, rather than on what the art says about the world apart from it. They are also the generation whose work can be seen as providing the bridge to the renaissance of content and pictorialism that has flourished in the globally expansive art markets of these first decades of the new century.

This reopening of contemporary art to pictorial conventions after a century-and-a-half of anti-pictorial formalist experimentation was entirely inadvertent. At least the Pictures artists I knew personally in the late 1970s and early 1980s never talked about their work as if they saw themselves positioned at a semiotic dead end--of being the final outcome of the formalist movements that overtook all the arts since Cubism in painting and sculpture. But the Pictures Artists were well aware that they had inherited a revitalized interest in the human body from Performance Art. They understood that the science of semiotics and its utilization by advertising, television and cinema was yielding a mine of information about how pictures propagated and perpetuated social and cultural codes. And they ultimately found that when the art of the body meets with the science of cultural codification, the most natural product is a pictorial art that reflects the way that social and cultural codes are conveyed by pictures. It is only some thirty years after the Pictures Artists began working that we can state with confidence that the Pictures experiment was itself a quasi-formalist process which, in restraining itself to reflecting the means and resources of art making, exhausted its aesthetic and conceptual possiblities in a circularity of narrowly-defined logic.

But once the Pictures Artists provided the stratagem to reintroduce pictures as an art that mimicked the way that society at large uses pictures to condition its cultural and moral codes, the gates of the kingdom had been breached. The hordes of artists eager to paint and photograph and film freely without formalist or conceptualist restraints and tautologies could now move into view, and the original agenda set for the Pictures Artists arguably became obsolete, or so broadened as to be enclusive of content in ways the Pictures Artists never intended. It's no surprise that the artists who survive this obsolescence are women--Cindy Sherman, Sarah Charlesworth, Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger, Laurie Simmons, Dara Birnbaum--all of whom have become associated with a feminist mimicry or analysis of the codes disseminated by conventional art and media responsible for the disparity of power among women. But aside from this feminist offshoot, Pictures Art became a virtual dead end coinciding with the end of the century of formalist self-reflection and the beginning of the new century of media recontextualization.

By media recontextualization I mean what art history tells us--that aesthetic and theoretical cul de sacs have a way of sprouting artistic offshoots that go unappreciated until they one day grow into regenerative movements that come to dominate the day. At the end of the 20th century, in the art we called Postmodernist, we culturophiles convinced ourselves of Modernism's exhaustion. We watched Formalism, Surrealism, Expressionism and other earlier movements all seemingly become revived by artists--but for the ironic twists that told us that artists weren't really reviving these outmoded movements at all, but saying goodbye to them by loading their iconic forms with ironic contents that were anything but formalist. Think of the seemingly abstract paintings made by Peter Halley, Philip Taaffe and Pat Steir, who respectively made flat parallelograms, vibrant op-art, and expressionist pours. Their art on first glace appears evocative of the formalist art of earlier generations of abstract painters, but in fact they were signifying cultural representations of prison cells (Halley), Islamic decoration (Taaffe), and Chinese waterfalls (Steir).

By 2000, the ironic impulse had become unnecessary. Direct and conventional representationalism had become widespread, rendering the tautological exercises of the Pictures Artists unecessary. In fact, the analysis of cultural codes that the Pictures Artists inherited from Conceptual Art was taken up by a new generation who wielded them ever more potently as theoretical and political instruments of dissent. Cultural codes are handled with exceedingly more finesse and with sharper implications in the photography of Andres Serrano, Shirin Neshat, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Sharon Lockhart, Bruce Yonemoto, Wolfgang Tilmans, Collier Schorr, Nan Goldin and Catherine Opie. The same can be said about the film and video of Bill Violoa, Christian Marclay, Matthew Barney, Yael Bartana, Diana Thater, Harun Farocki, Doug Aikin, and Rodney Graham. In painting, culturally-codified picture making was revitalized with great accomplishment by Gerhardt Richter, Eric Fischl, John Currin, Jenny Saville, Lisa Yuskavage, Shazi Sikander, and Dexter Dalwood. And in digital animation the Pictures legacy imbues the virtual worlds of Mariko Mori, Thomas Demand, Claudia Hart, Kurt Hentschlager, and Matthew Weinstein. Some of this work retains the reflection of its media that grows from twentieth-century movements, but much does not.

It is against this backdrop formed by such younger artists that we now reassess the Pictures generation. And the backdrop isn't always kind to them. The Goldstein and Bender shows convey this. But not only because so much art today eclipses theirs. Unlike the more narrative strain of art that grew out of performance art through the innovations of Yvonne Rainer, Joan Jonas, Laurie Anderson, and a host of younger artists after them, the Pictures artists didn't have the luxury of investigating the infinite pathways of content through which the narrative impulse can permutate. In other words, the Pictures artists could grow neither outwardly to the world nor inwardly to subjective visions, so saddled were they by the metacritique that became the fashion of their decade.

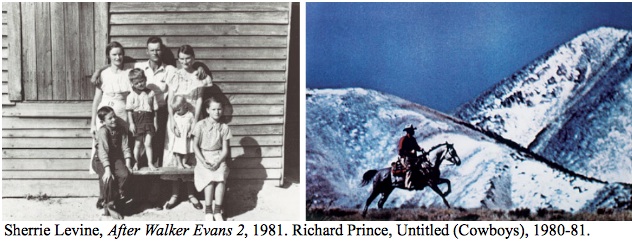

To grow inwardly or outwardly means that the Pictures artists would have had to resort to conventions and contents well beyond the critique and emulation of media and signage. They could only appropriate and recontextualize pictures referencing the codifcation and structure of pictures and the performance of making pictures, not simply make pictures of the world outside this process. To do more meant that they either became conventional painters, photographers, advertisers or scientists. Some of the Pictures artists--Charlesworth, Sherman, Levine and Prince especially--made brilliant variations on essentially one theme, though their capacities for convention within such theoretical confines had as much to do with their proclivity for aestheticism as with pointing viewers to the cultural codes that discreetly, if not unconsciously, inform and condition whole populations to the modes of behavior culturally prescribed and proscribed from above.

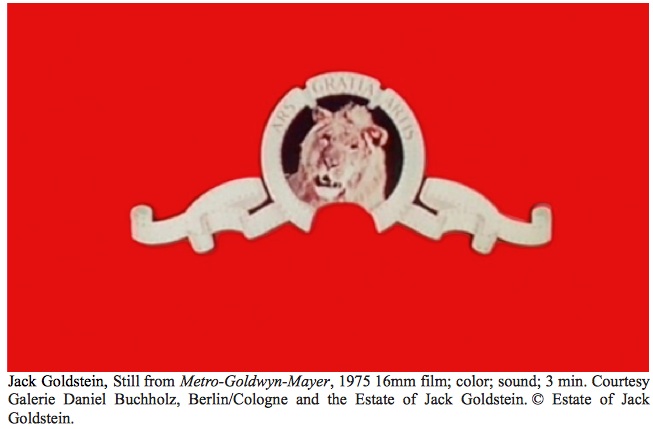

Jack Goldstein, in film, audio art, and outsourced painting, and Gretchen Bender in single-channel video and multi-channel installation art, stopped short of taking pictures to their reductivist conclusion by making branding the object of their analytical sights. But neither were the first to chart out the structures they use to isolate and extrapolate brands. Goldstein is heavily indebted to Warhol, Ono, Snow, Frampton and Sharits--structural filmmakers who foregrounded the medium of film by making the frame, the filmstrip, the projection, its light, and the passage of time their subjects. Goldstein uses the same formal strategies, but to place stress on the pictorial signage or brand projected, not the medium projecting.

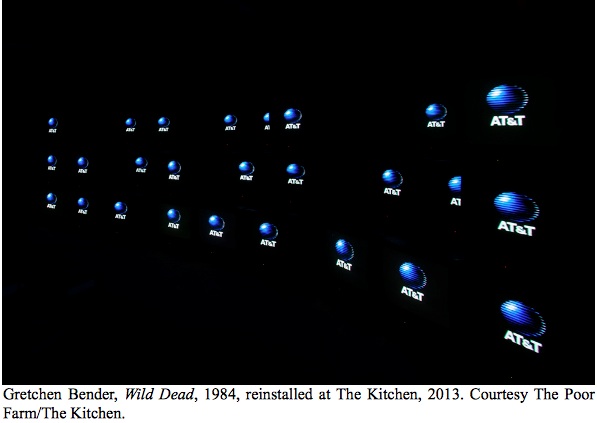

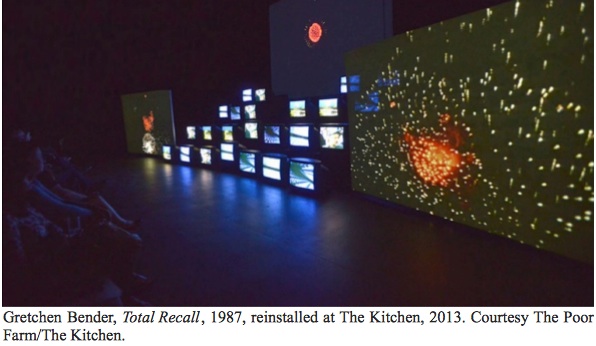

Bender's video, including the tiered installations some writers have mistaken to be her innovation, are equally indebted to the electronic brood of structuralists: to Nam June Paik, Woody and Steina Vasulka, Ira Schneider and Frank Gillette, Valie Export, Gary Hill and Dara Birnbaum. Similarly, the work of Kit Fitzgerald and John Sanborn, and a myriad of music video directors and editors inform Bender's single channel audio and video collaborations with Robert Longo.

But Bender's installations Wild Dead (1984) and Total Recall (1987) achieve a structural and temporal coherence despite their deployment of such stratagems as network and institutional dismantling and image barrage. If these strategies seem dated, it is in part because video has extreme media limitations in terms of its hardware presentation, and in part because of Bender's recourse to reductivist and repetitive imagery. Video art is so encumbered by media restraints, that for this viewer, walking into The Kitchen this week recalled the 1990 Whitney Museum exhibition, Image World: Art and Media Culture, composed as it was of the electronic barrage of some 65 artists and groups. It was one of the shows that had neglected Bender while supporting the careers of less elegant artists. I raise this not to belittle Bender, but to summarize the difficulty she and other video artists who entered the medium in the mid 1980s faced--a time when the structuralist, poststructuralist and deconstructive critiques of mainstream media and the circularity of media imagery passing between the artworld and popular culture all seemed to have been well used if not exhausted.

There is also the all-too-close alignment of Bender with commercial music videos that keeps her from being fully appreciated, especially as the younger audiences who have since matured were acclimated to MTV as infants. Bender may have promoted her work as dismantling genre cliches, but she ends up appearing to relish the cliches more than deconstructing them, while relying heavily on the anarchist associations of punk and post punk music and dwelling too lovingly on the performances of rock musicians to take less cliched and reductivist measures required by the mid 1980s to transcend musical and network conventions. Of course, by the late 1980s, the jargon of deconstruction theory was choking, rather than supporting, the practices of artists. The trouble with popular waves of theory is that when audiences reach the saturation point of the theory in question, the jargon associated with it, along with the artistic echoing of such jargon, seem to spoil overnight.

As for partaking in appropriation, neither Goldstein nor Bender rise to the level of celebrity theft that distinguishes Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince, largely and ironically because the thefts they engineer aren't nearly as complete. Levine and Prince disappear into their appropriations as completely as gifted actors disappear into their roles. In allowing their sources--the artists or brands appropriated--to stand for them, they ultimately become co-identified with their sources. The audacity of such a gesture is comparable to the audacity of Duchamp introducing readymades and Warhol introducing the branding of ordinary supermarket products as the iconography of his painting and sculpture. By contrast, Goldstein's resemblance to Warhol and Bender's to Paik, flatten their contributions from above. At the same time the personal, artistic signature each imposes on their appropriations of commercial brands erodes their contributions from below. Levine and Prince rarely left such signatures in their early appropriations. The result, comparatively speaking, is that Goldstein's and Bender's restraint in appropriating sources is the equivalent to deadly hesitation in a gunfight. Levine and Prince don't hesitate, and their shots are dead on. Goldstein and Bender are taken out in the end for not giving it their all.

This doesn't mean that Goldstein and Bender haven't carved out evocative niches for themselves in their handling of commercial branding. Nor that they are uninteresting. There is much room for their best art because as spectacle their work resonates. The expansion of the art world that many audiences long for requires that we lend our time not just to the canon of artists who make significantly singular art history. Art history, after all, is buttressed by the variations of less iconic artists who reinforce audience interest onto the new. If the Met show alerted market watchers to anything, it is that the majority of Pictures Artists, those who have gone neglected in recent decades, reinforce the work of those artists whose careers are most memorable--Sherman, Salle, Charlesworth, Kruger, Levine and Prince--and who sustain both market and academic interest.

Both Goldstein and Bender may yet profit with increased exposure on the internet. Goldstein is already a presence on youtube, and garnering a new following there. Bender's best work, at least as indexed by the two large multi-channeled works shown at The Kitchen, will require permanent installations--the kind that Paik's Information Superhighway enjoys at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington--to keep audiences, and art historical discourse, coming back to her.

MICA-TV's Carol Ann Klonarides can be found on Youtube in the video file, Little Deaths, lamenting that the "revolution" begun by avant-garde media artists grew into a global mega-corporate facility of theft that inflicts a multitude of little private deaths on digital art. But, really, what could anyone have expected, when opening the doors to artistic death through theft by its very nature means being overrun by amateur copies of copies of copies. Did any of the Pictures Artists really expect to keep image appropriation within their own artistic restraints? Any who did expect such entitlement would have been fools. We need only remember Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's proclamation that all property is theft. From the day that property hypothetically spread with the neolithic tribes of the first villages, theft came with it. As did art making. As did pictures. Property, art, pictures and theft appear to have been tied together from the start.

The theft of Crimp is his proprietary claim to a theory of picture making that belongs to everyone. Any artist who makes pictures has to grapple with the self-consciousness of making pictures, however intuitively the process is worked out. The Pictures Artists did no more than to make the process of picture making seem vital to what was left to the avant-garde in art, while highlighting the extent to which image theft can be justified. But what is truly significant about the Pictures Artists is that they demonstrated to the art world, at a time when it was all but forgotten, that a door formerly closed and suddenly made to open wide, receives the horde who will fall in, take over, and steal everything in sight.

Pictures Art is dead. Long live Pictures Art.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.