On International Women's Day, 2011, I published on Huffington Post, Part 1 of "XX Chromosocial: Women Artists Cross the Homsocial Divide"--a 7-part series surveying art made by women that conveys the many complexities of the homosocial enclaves of men and women and the social codes that keep them in many senses apart. This year on International Women's Day, I'm publishing Part 7, "Women Looking at Men Loving"--the final installment in the "XX Chromosocial" series. Links to the first six parts follow the article.

Women's homosocial art is different than most feminist art made over the past forty to fifty years. It extends both beyond and beneath the terrain in which feminism challenges patriarchy to articulate what we've come to call the homosocial divide--the great, if willful, breach separating men and women that is as much the result of women's desires as it is the requirement of men. In this respect, the homosocially-oriented work by the several women artists discussed in parts 1 through 6 articulate nearly every fathomable aspect of women's desire and socialization, either as they have been historically legislated and imposed on women by men, or newly analyzed and codified by women in the effort to achieve gender parity.

Yet, as comprehensive as has been the art of women about women over the last half century, by comparison it seems astonishing that so little of women's art essays the male homosociety--what occurs when men are alone with men, or boys with boys. Men, on the other hand, have shown no hesitation to depict either men or women homosocially. We need only recall John Boorman's film, Deliverance, Oliver Stone's Platoon, or Terrence Malick's Tree of Life to recall the intricacies of male homosocialization projected onscreen. And then there are the numerous male artists who have made women's homosocieties the subject of their art--Ingmar Bergman's Cries and Whispers and Yimou Zhang's Raise the Red Lantern stand out in the history of cinema. Or we can easily summon to mind all the women populating the paintings of Alex Katz and the sculpture of Edgar Degas, and most recently the formidable women body-builders who command our attention in the photography of Martin Schoeller.

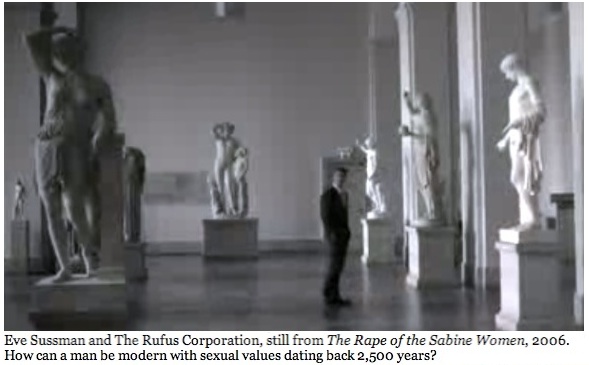

One of the more renowned works by women to depict sexual politics as the product of homosocial conditioning is Eve Sussman's 80-minute video, The Rape of The Sabine Women. An impressionistic, at times surreal, composite play, dance, and musical, Rape proceeds from scanning the range of behaviors from gender conformity to gender defiance as a newly emancipated generation of women cross the gender divide by taking charge of their own sexual needs instead of merely attending to the needs of men. Made with The Rufus Corporation to an original score by Jonathan Bepler, and with choreography by Claudie De Serpa Soares and costumes by Karen Young, Sussman cast hundreds of young men and women to act out the millennia-old sexual rituals for men and women at the outset of the 1960s--the decade that in the West is the last to see the male homosociety go unchallenged in their domination of the codes of sex and gender.

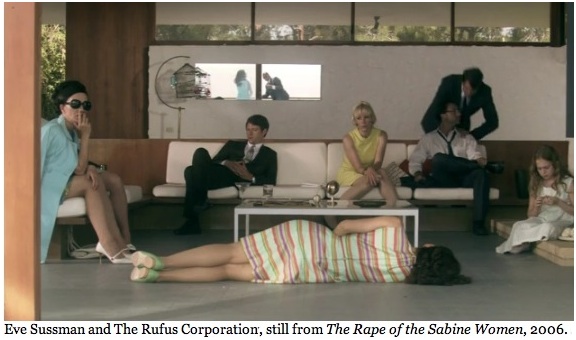

Sussman's work is by no means analytical of the homosocial condition, but her semiotic intuition is precise in ferreting out the iconography of homosocial codes at work as men and women at first act out the millennia-old mating rituals each generation must revive--but then, as befits the 1960s generation, which they transform before our eyes. Men and women virtually circle each other with singular purpose, yet as the women depart from the homosocial script that women for centuries followed, we see both men and women uncertain, even confounded, about how to get what they need and want from one another. Sussman doesn't need to reference the introduction of The Pill and the other contraceptives introduced to the public in the 1960s to liberate sex from the risk of unwanted pregnancy. It suffices that the period clothing, hair styles and furnishings that identify the decade registers onscreen as the setting for a hesitant sexual curiosity that evolves first into awkward, then bold, then outright crude gratification.

Sussman's restless, attractive and affluent creatures are reminiscent of Alain Resnais's effete socilites populating his film, Last Year At Marienbad. But Marienbad was made in 1961, at the beginning of the sexual revolution, and before people knew what such a revolution entailed, and what would be its outcome. Sussman's mimicry of Last Year at Marienabad is largely restricted to matters of narrative style, and then only on the surface. For whereas the eroticism of Marianbad is perpetually stalled, or perhaps perpetually caught in a loop of some unfufilling and effetely absurd chase, (as written by the novelist and screenwriter Alain Robbe-Grillet), Sussman's male homosociety is bewildered not by a chase that leads nowhere, but to more sexual opportunity among a newly liberated homosociety of women than they know what to do with.

Sussman's sexual ritual begins as it always did, with young men and women traveling in same-sex packs as they sniff out the haunts of the opposite sex. More evocative are the opposite but converging homosocial structures driving the scenes leading to the "rape." Sussman makes it difficult for us to turn away from the twin studies unfolding―those of brash young men and nubile young women moving on mutually exclusive tracks of compulsive behavior wildly at odds with custom and ritual. We know that in their combined sexual force and social alienation, both sides head toward the inevitable collision and exhausting aftermath that will lead to yet another sexual domination of women, yet this time we expect it to signify the last unchallenged decade of male homosocialization. Sussman here seems to be defiantly against the facts of history as her women appear as ravenous as the men, and without regard for what their sexual liberation will mean to them in the long run. Many today are still asking the question asked in the 1960s: "Will women contribute to their own abandonment by men (as their mothers taught them), even as men become exceedingly more accustomed to the new access to sex on demand? It's a question that reveals as much about women's changing homosociality as it does about men's intransigence in the sexual mores of antiquity. Once again, the male homosocialiality remains enigmatic, while the homosociality of the women is displayed as if they were specimens under glass.

What Sussman does quite explicitly and elegantly in Rape of the Sabine Women is contrast the 1960s with the origins of the Roman legend in a time enveloped in the mists of cultural amnesia. If we believe the myth, Rome was fathered by a womenless clan of Romans who invade the Sabine city to abscond with their women, and with whom they found and populate the city and empire. The legend informs Sussman's scenes of restless young men walking among Greek and Roman classical sculpture or the high reliefs of the Pergamon Altar in Berlin. Other scenes are shot in Athens and on the island of Hydra, all discretely hinting at the Bronze- and Iron-Age origins of our current homosocial conformity to certain patriarchal and matriarhal codes and gender authorities reputedly having founded the religions that would legislate sexuality from the Bronze Age to the present. It is because the codes legislating sexual and gender morality were established some three-to-four thousand years ago that my series, "XX Chromosocial," consistently refers back to the Bronze and Iron Ages. For by uncovering the codes imposed by men on women's homosocieties all those centuries ago, the art of 21st-century feminism is rightly thought to be chipping away at the male homosociality that denied political, social and sexual gratification to women more vigorously once the metal armature of war elevated the status of both war and men.

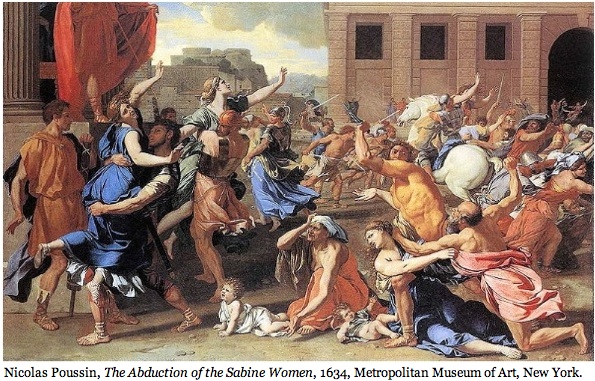

But Sussman's Rape of the Sabines also refers to a third, intermediate, signification of liberation. The legend of Rome's founding with the abduction of the Sabine Women was among the favorite classical subjects of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century painters, the most renowned being the two Rape of the Sabine Women compositions (1634-38) by Nicholas Poussin, one hanging at the Metropolitan Museum and the other at The Louvre. This at least provides us with one reason why the men in Sussman's film don't appear to evolve as do the women. Male sexuality can be said to have peaked in its liberating freedom in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. We need only to recall Poussin's painting to see this. For Poussin painted his two Rapes not long after the elite male homosocial order had liberated itself far enough from the Roman Catholic Church to celebrate the previously prosribed secular ("pagan") narratives from classical times. This newly rediscovered classical literacy enabled artists to reinforce the theater of male sexuality―the supreme example of which is Poussin's graphic depiction of rampant and public abduction and rape. However moralistic in intent the paintings were purported to be (as a 'lesson" in the horrors of rape), Poussin's masterpiece exposes the pornographic, even monstrous desire men as a homosociety harbor and are capable of unleashing in the absence of law.

Never mind that the equation of power that Poussin's generation expressed with their newfound freedom to paint sexuality voids any truly erotic urge and supplants it with a simultaneously voyeuristic and active sexual sadism that is nowhere better embodied in the history of Western art than in Poussin's two Rapes. Amid such a grotesquely orgiastic theater of enforced sexuality it seems no exaggeration to suggest that the public gang rape is, if not a manifestation of repressed homosexual desire, certainly it is unleashed with the approval of other men in mind, however much it purports to be sanctioned not for homososexual gratification but entirely for the homosocially-sanctioned "virtue" of male heterosexual prowess. Poussin's Rape of the Sabine Women are paintings that in their most theatrical sense proclaim, even celebrate, the male sexual liberation that begins with the renaissance--a liberation that women must wait another 500 years and more to achieve. In short, Sussman's citation of the Sabine rapes cannot unleash a newly liberated homosociality for men because male sexual desire was already sufficiently released variously, and in stages, from religious restraints in the 15th 16th and 17th centuries, and the male homosocial code of sexual mores has remained largely liberated in the West ever since.

It's this delay in the timing of women's liberation from religious mores, compounded with the sense in the 1960s that women were freed biologically, that accounts for why Sussman softens her depiction of the Sabine rape scene by converting it into an orgy within which women have exceedingly more say over their contribution to the sexual free for all. It's clear that Sussman has more of an ironic interest in drawing parallels with the last great epoch of misogyny about to be set upon by feminism than in staging scenes of barbarism.

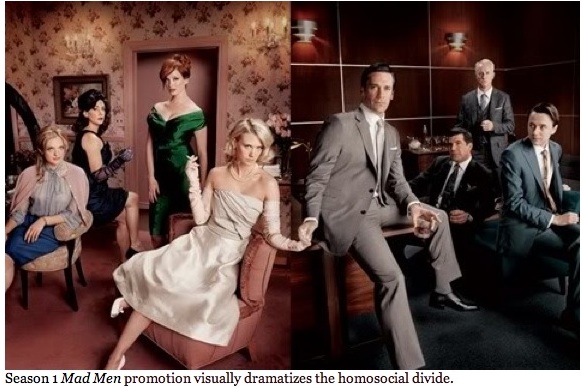

It is no mere coincidence that Sussman's making of Rape of the Sabine Women coincided in time with the making of the hit cable program, Mad Men, what is, if not television's first homosocially-conscious television program, certainly it's first homosocial parody of the way we were, narrated with a knowing sexual-political condescension and impetus to set the record straight (no pun intended). Mad Men shares much with Sussman's Rape of the Sabine Women in terms of its re-enactment of the decade in which the new sexually-liberated order of Western women's homosociety collides with the liberated male homosociety rooted in the 16th and 17th centuries. Of course, unlike Sussman's film, with its explicit referents in the late renaissance and the Bronze and Iron Ages, Mad Men's temporal referent is no further away than some four-to-five decades, and thereby nests in a more contently civilized mythos renown for its penchant for both high stylization and vivid liberation cultures. But as far as Mad Men shares the 1960s with Sussman as its stage, the show's promotions display a remarkably Sussman-like, imbalanced bifurcation of 1960s gender codes.

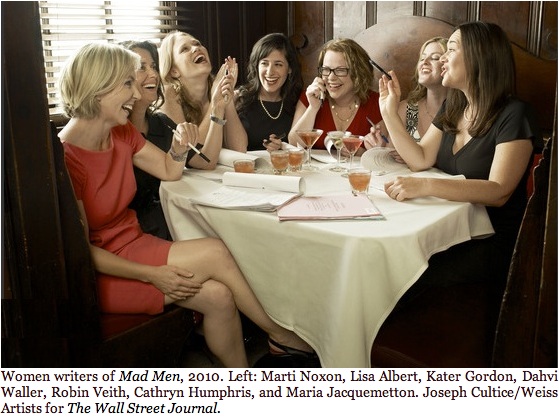

To watch either Rape of the Sabine Women or Mad Men is to remember (or to learn) just how dramatically feminism and gay activism chipped away at a male homosocial domination that, after barely fifty years, seems to us today near as draconian and feudalistic as arranged child marriages and mail-order brides. It seems only natural that Mad Men differs from other shows not only because it was made after Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's thesis of the homosocial had become a key theme in academic American feminisms, and more recently feminist and LGBT art. But then Mad Men is also noteworthy for having a large percentage of women writers outnumbering male writers. The program may have been conceived by TV scribe, Matthew Weiner, but no doubt its homosocial resonance and feminist retrospection has to be equally credited to, what the Wall Street Journal hails as, the "Women Behind Madmen"―the seven women among the nine series writers in 2009: Lisa Albert, Kater Gordon, Cathryn Humphris, Maria Jacquemetton, Marti Noxon, Robin Veith, and Dahvi Waller. It's hard to imagine the misogyny of men so overtly paraded onscreen if women hadn't been instrumental in bringing the project up to feminist code.

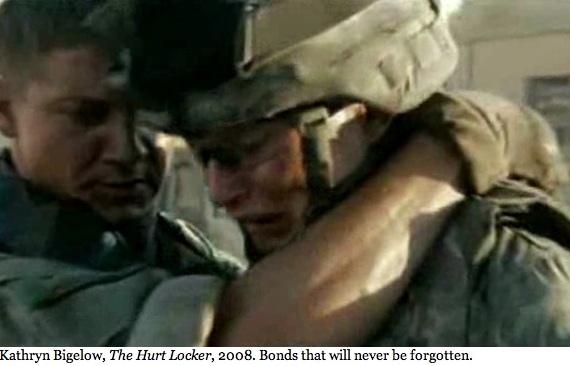

And yet a dearth of homosocial film productions arguably is one reason why Kathryn Bigelow's film, The Hurt Locker, so resoundingly drew support among the film critics and guild awards in 2009. Although the media has lauded The Hurt Locker for affording audiences with the most acute view of the Iraq War to date―some have even hyperventilated it as the best war film ever―the male homosocial register is so unacknowledged by the mainstream as to keep the public from appreciating Bigelow's greatest accomplishment in the film―her portrait of what many men may count as the last male homosocial preserve. (Tragically, this is a sentiment that accounts for the thousands of rapes and assaults of American women in the military, and their successful cover-ups at all levels of the chain of command, that have been courageously brought to light in the 2012 documentary, The Invisible War, by Kirby Dick.)

Although The Hurt Locker is scripted by Mark Boal, a journalist who had been embedded in Iraq, Bigelow brings to the enterprise a perspective on men, masculinity, power, and desire that men themselves are less apt to recognize than women. In this respect Bigelow's observations on men aren't so remarkable for a woman to record as much as they have historically been outside the purview of women by male decree. Even women inside the military today might find access to such men as the U.S. Army's elite bomb squad unit restricted, if not by policy, certainly by the men who feel themselves to be observed by an "outsider" incapable of understanding their bond. (Wasn't this Ridley Scott's point in G. I. Jane in 1997?) The degree to which Bigelow's film is inferential―based on her own and other women's observations of men in tight-knit homosocieties at home, at play, and at work, even in extremely tense and dangerous moments―can only be speculated on. But the homosocial barrier has not only to be acknowledged when considering the degree of verisimilitude possible in observations on one homosociety by members of its opposite, if mirroring, image. The homosocial divide has to be crossed by a woman if she wishes to craft a narrative about men at war, even if she finds the curtain of male quarters closed to her.

But in being able to comprehend male deportment without being male is evidence that there is much more that men and women share than we've been raised to believe. It is why women see in men so many of the things men see in themselves and more―much of which Bigelow shows us on the screen―specifically the extremes to which men are driven by, if not testosterone, certainly the myth of testosterone (though most likely both). It is why women have championed Bigelow's film. And if Bigelow has managed to garner men's support where so many women's films haven't, it is because she portrays men as so many men love to be portrayed―or think they love to be portrayed. They may not see Bigelow's scrutiny as immediately as do women. To my mind, Bigelow manages to portray the fraternity of men with a subtle reflexivity that allows cinematic recognition, and subsequent, if more arcane, analysis of the male enclave of elite soldiers in combat without overtly judgmental commentary. But make no mistake. Bigelow is making judgments about men throughout her film--judgments about their affections for other men and about their disaffection with women, however open ended her conclusions about both remain.

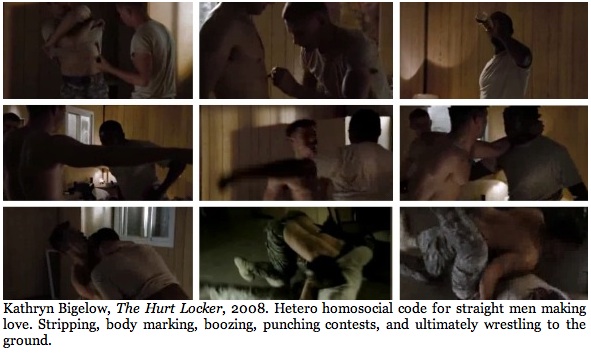

One scene in The Hurt Locker is particularly telling about the expression of affection among many men being shaped by homosocial codes that prescribe and proscribe how to love ne another. Three of the soldiers from Bravo Company--the three who spend their days together dismantling live explosive devices--are disclosed as also spending their nights together drinking heavily, punching each other in the gut without holding back, and wrestling one another to the floor until one knees the other in the groin. Such scenes tell us volumes about the simultaneously emotional restraints and releases of volatile emotions that many heterosexual men believe they require before they can enjoy mutual affection. For cinephiles who follow Bigelow's oeuvre, It is obvuious the director reprises the entirety of her 1978 student film, a short called The Set-Up), in which two men fight each other for a prolonged period in a dark alley as the semioticians Sylvère Lotringer and Marshall Blonsky, in Bigelow's words, deconstruct the images in voice-over with its emphasis on men, masculinity, violence and power. Needless to say, on the soundtrack, love is nowhere mentioned among the priorities the men should share. More likely they loathe one another. But the seemingly endless scene, like the ballet it resembles in it choreographed stylization, and in being void of context (the reason for the fight) as well suggests the conflict could be one of a hurtful love.

In the The Hurt Locker, context sets us straight (this time pun very much intended). The tension of daily trauma is only the most obvious release. Love, albeit between preseumed hetersosexual buddies, is the undeniable, if calloused over, primary affect--the affection men have for one another tempered by the stoic rearing that induces men to renounce their love for one another before the male homosocial megalith of feigned indifference―or until the indifference becomes no longer just feigned. From the first scene in which Bravo Company is deployed to dismantle a bomb in the center of a Baghdad street, Bigelow captures the bravado of the men who, despite the danger and mounting tension, behave as randily as if in a football locker room. All brute and brawn, replete with penis jokes connoting who's biggest and best, horsing in the face of adversity is what passes for naked displays of affection breaking through the instilled loathing of affection men are conditioned by. Forget that their affection is just for want of brothers; Bigelow's men are supposed to have had the love of manliness knocked from them in childhood, yet here it is dripping out with their sweat, and sometimes their blood.

Bigelow may be the first woman feature film director to bring us significantly close to the male homosocial condition of having manly passion flattened into trivial occurrence. Glimpses of something inside Bigelow's men slips through the screen that we don't find issuing from the homosocial reveries of her male peers―directors like Clint Eastwood, Steven Speilberg, Terrence Malick, or Oliver Stone. We see traces of the boys men were, boys who had their affections for one another distended by pack loyalty, supplanted by contact sports, transferred to toy guns, run over by video game rampage―all meant to sponge up the energy of male affection and convert it into a competition. In some all-male enclaves such disaffection is so complete as to be supplanted by all-out enmity, a conflict that keeps love at bay, not unlike the barracks scene where SFC William James and Sgt. J.T. Sanford "unwind" by punching one another full force square to the stomach, unleashing Sanford's hairspring aggression and a switchblade to James's throat. The Hurt Locker is an extreme view of men under extreme circumstances, but Bigelow is doing no more than reminding us that grown men often show their affection for one another clumsily, violently, not knowing what to say to one another in earnest, nor of what they should feel for one another deeply.

It is a view that women see of young men in particular, boys really, who know so little about how to relax in each other's company without horsing around, throwing gum and spitting at one another, and of course wrestling, all because they've at an early age had what they feel for one another cut off from their consciousness. Is it any wonder that in particularly rough urban neigborhoods, six-year-old boys transform overnight from gentle, sensitive lambs who loved with complete trust into angry pack animals who smash windows throughout the neighborhood. By fourteen, gangs of boys graduate to sprees of random carnage; by eighteen they are incarcerated with hundreds of men as angry as themselves.

Bigelow has amply filmed this restless and criminal male in her earlier work, The Loveless (1982), Blue Steel (1989), Point Break (1991), and Homicide: Life on the Street (1996-99). But if The Hurt Locker is a more compelling study of the tension between male love and disaffection, it is because we find ourselves not at odds with the distended libidos of unsocial men, but enthralled with the acts of bravery that socialized men are capable of producing for the assumed good of civilization. These are men we feel protected by―always the redeeming force of testosterone, to say nothing of the impetus for its hormonal and genetic evolution. It is the principle that enables Bigelow to frame the Iraqi military base as a microcosm of manliness, one in which, despite the unprecedented number of female American military combatants, is a place where women in the film are invisible and manly men run unfettered, with exhilaration roused by combat prowess drills, and fraternization encouraged with exaggerated crudeness in manners. Here a man can flourish in that atmosphere of off-color jokes he mythically relishes; where, like some hyena on the Serengeti plain we see on nature shows, he can heckle and whistle at the sight of a woman or an effeminate man. Reinforced by weaponry and fraternity, he can behave as recklessly as regulations allow, with his adolescence perpetuated and pumped in the name of national security. By the time his company is called to secure a city street, detonate a bomb, or engage in a shootout, he is emboldened euphorically by his replication in several thousand men like himself, whereby he finds the freedom to unleash upon an enemy combatant all the circumvented rage he has stored up his entire life.

Bigelow may not dwell on death, but when we see it we know she is telling us that dead men may not know the men whose bullets or bombs kill them, but it may be safe to assume that they are men who feel the same things for men as the men they kill and are killed by―being denied since they were age six of the male-male love they cherish. A fallen soldier and his killer are twins in that way, finding release in the orgy of conflict that men think they believe is for the safety of their nations, the perpetuation of their faith, for democracy, or some other ideal that is really but a sublimation of deeper passions. Bigelow is exemplary in showing us that men not only discover under duress of battle the extent to which they love their brothers, but that their love far exceeds any hate they could summon for the enemy. (More often soldiers claim to feel bewilderment about them). The ancient Spartans knew love eclipsed hate as a stimulus and sustaining force for battle. It is the reason they encouraged soldiers to take male lovers whom they would fight alongside (something we should be wary of the Pentagon considering in retiring Don't Ask, Don't Tell). But whether the imagery propelling men to fight is that of fighting alongside lovers or alongside brothers, the affection heightened by combat is both the cement between soldiers and the fuel that keeps men killing regardless of what overarching ideology is pronounced as rationalization of war.

Bigelow isn't by any means the first director to show us how, after combat, so many men―even those married and raising children―find themselves restless and remote once away from their brothers and alone with spouses, whether in public or at home. And why wouldn't they be? Even before combat they hunted and bowled and boxed and sprinted their affections out with men. How often is a wife or a daughter or a girlfriend or a sister brought to the game or the track or the stadium or the gym with them? Of course, the fraternity of men that Bigelow depicts has greater resonance than previous war films because her Bravo Company is deployed in Iraq. War films set in Europe, and even in Asia―regions where women have greater visual presence if not autonomy than in the Middle East―are by geo-cultural circumstance accented with scenes in which women provide recreation if not support. Bigelow, by contrast, amplifies the valence of male homosociety by abjuring scenes of the soldiers' women at home (think of Terrence Malick's lyrical imagery of women lovers at home in The Thin Red Line, the stirring image of a mother sinking to her knees at the sight of military personnel outside her front door in Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan.) But for the fleeting glimpses of veiled Iraqi women on the street being escorted away from suspected bombs by American GIs or peering from dark windows above, The Hurt Locker is almost devoid of imagery of women until the very end―and then in the processed cereal aisle of a cavernous supermarket.

Even at home, the brevity of scenes between Sgt. James and his wife are so remote and abrupt as to be unsatisfying from both the perspective of a man and a woman. With James returning within weeks (within minutes in real screen time) to another year of duty, Bigelow prompts speculation whether her soldiers are repressed homosexuals or simply that breed of heterosexual male who prefers starkly divided homosocial territories afforded by countries like Iraq, Egypt, Iran, Morocco, and Pakistan―cultures where women don't accompany men outside the home. In such places it is the men who line the bars and fill the tables and litter the parks. Married men can spend their nights and days entirely without the women they profess to love.

At the end of The Hurt Locker, Bigelow asks us to consider which is the greater love, the greater force, when intimacy between a man and a woman amounts to minutes and fraternity clocks in at eight, twelve, sixteen hours a day. And for 365 days a year―the duration of Sgt. James' renewed tour of Iraq announced in bold titles at the film's conclusion. In such a homosocial equation, global combat cannot but appear as the effect of a world that outlaws love among men but fails to wrest the primal flow of male homosocial attraction, whether it spills over into conclaves of felons or soldiers, stockbrokers or politicians.

--This series, in seven parts, has been written in tribute to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Louise Bourgeois and Nancy Spero.

Parts 1 through 6 of "XX CHromosocial: Women Cross the Homosocial Divide" can be found at the underlined links below:

Part 1: Women's Hidden Homosocial Past, Shirin Neshat, Laila Essaydi, Deepa Mehta, Marina Abramovic, and Angela Ellsworth.

Part 2: Gender As Performance & Script, Yvonne Rainer, Sarah Charlesworth, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Judith Butler.

Part 3: Women's Art of Renewal (Disseminating New Codes and Enculturations): Carrie Mae Weems, Vanessa Beecroft, Sharon Lockhart, Catherine Opie, and Lisa Yuskavage.

Part 4: From Victim to Victor, Women Turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out: Artemesia Gentileschi, Käthe Kollwitz, Frida Kahlo, Judy, Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, Ana Mendieta, Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Janine Antoni, Kara Walker, and Sue Williams.

Part 5: Did Men Invent Art to Become Women? Must Women Become Men to Make Great Art? (Leveling the Gender Divide) Sherrie Levine, Deborah Kass, Collier Schorr, and Jenny Saville.

Part 6: Women's Mythopoetic Art: Going Back to Start, Heroically. Marina Abramovic, Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero, Mariko Mori, Shahzia Sikander, and Claudia Hart.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.