Martha Wilson's solo show, I have become my own worst fear, is on view at P·P·O·W Gallery, 535 West 22nd Street, 3rd Floor, 212-647-1044. Crazy Lady, curated by art critic Jane Harris, and Det Syke, new paintings by Jordan Bunch, are on view at Schroeder Romero & Shredder, 531 West 26th Street, New York, (212) 630-0722. All three shows are up through October 8, 2011.

I'm not the sort who ordinarily hears Peggy Lee singing in my head, but when I walked away from two shows in the same day comprised of women artists confronting their worst fears about themselves as women, and a third show by a man attempting to humanize the face of 19th-century "female hysteria," I couldn't shake from my head Ms. Lee's jaded but poignant and repetitive refrain, Is That All There Is?

The song was my involuntary mind's commentary rising up in response to Martha Wilson's solo show, I have become my own worst fear, at P.P.O.W.; art critic Jane Harris' group selection, Crazy Lady, at Schroeder, Romero & Shredder; and Lordan Bunch's Det Syke, a series of paintings and studies in oil derived from 19th-century photographs documenting women diagnosed with hysteria, being shown at the same gallery. I don't mean this in any way disparaging to the artists or their subjects. The song in fact asks the kind of question that the subjects represented in these shows ask--or in the case of the so-called hysterics and schizophrenics, which they act out--long after the pain of being deprived of the things and people they held dear, and the dissolution of their hopes and expectations, subsides.

"Is That All There Is?" is an open question that on the surface belies the emotional disengagement from life that it more deeply represents. It is why, after humming its tune a few days, I realized I should make the song my gauge of the realism and depth found in these three shows. For "Is that all there is?" is no less than the anthem of the emotionally detached state any one of us can fall into, the reflex of the woman or man whose buildup of anxiety has reached such an alarming level that it has become necessary to disengage from one's surroundings, friends, family and life--whether physically removing oneself, succumbing to the mind's natural defenses, or by reaching for medication.

It is common to hear people who have reached a certain stage of life, or who have suffered severe emotional detachment, complain that they have developed a sense of unreality especially regarding their past; they've become unfeeling and have a vague sense of something missing from their lives. The most severely inflicted retreat into catatonia--a state of total uncommunication. For these people, "Is That All There Is?" represents the stage of resignation, retreat and hardening resolve that protects them from the society judging and excluding them.

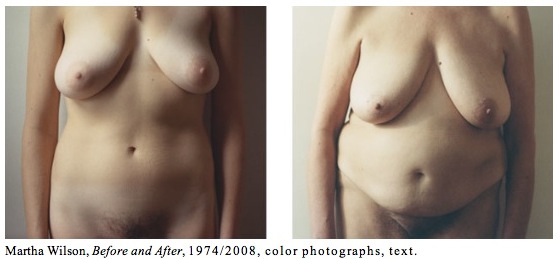

On my second visit to the three shows, I found that the most convincing artists were possessed of the signage of this intellectual detachment in their assessment of a wide range of behaviors and fetishes. The Martha Wilson show is altogether the most sanguine and even tempered of the three. And Wilson manages to make this period of maturation the most compelling phase of her life project of documenting her body's record of time's passage.

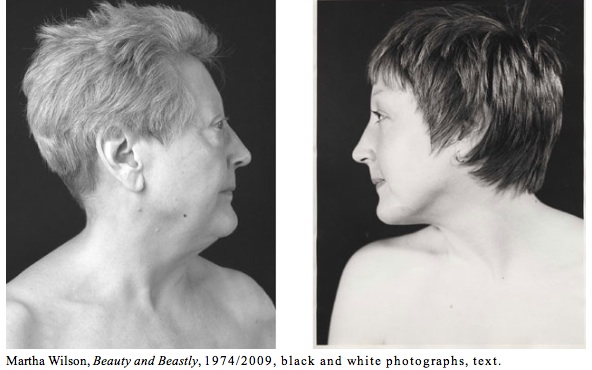

The gallery smartly included glimpses of work made when Wilson was decades younger, a period in which she would manipulate her appearance to project what she might look like with added weight, age, camouflage and bodily distortion. Now, as if she rode a time machine back in time, her aged persona meets up with and challenges the disparities of her youthful foresight. Yet this phase in Wilson's artistic production appears to be at times defensive in relying so heavily on self-deprecating humor and over-characterizations with clothing and assumed personas. And why shouldn't she resort to such tropes? We reach for what we can to cope with the injuries of time. Still, it is Wilson's most frank work, that showing her without anything more than the makeup and hair color she is known to wear in public, that is the most effecting.

It doesn't hurt that Wilson's show is at times self-possesed to the point that the artist shows herself to be more of a theatrical entity than an open book highlighting the private individual she must be. But that is the price for offering one's body up as a medium. Besides, defensive theatricality too is a manifestation of time's injuries, however manneristically and bravely Wilson addresses it.

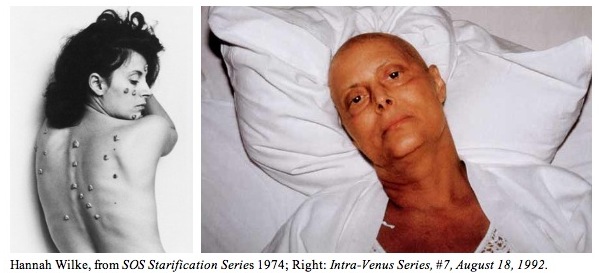

Because courageous public self-assessment like Wilson's is so rare, it summons to mind the work of another brave self-documenting feminist, the late Hannah Wilke, an early contemporary of Wilson's. It's an unfair comparison in that Wilke's documentation tragically captured her premature demise to lymphoma, a condition to which Wilke answered with unparraleled courage and pictorial frankness.

Like Wilson, Wilke's life art was largely self-referential: the artist posed as sculpture to be shaped, or canvas to be covered over (most famously with gum stretched into the shape of a vagina), a vehicle of narrative, documentation, and her own muse. But unlike Wilson, Wilke's movie-star beauty and eager nudity made her a target of early artistic feminists. That all changed when, in her early fifties, Wilke's narcissism underwent the most dramatic conversion with her body's consumpton by disease, and audiences witnessed her youthful eagerness to show off her beauty proving itself to be but preparation for Wilke's unhesitating display of her own demise and death in a wholly unsentimental, even stoic art.

I said it's an unfair comparison between the artists. At the same time it's hard not to expect the same from an artist as brave as Wilson. It's a too-horrible fate to wish such a demise on anyone, and yet the artist's demise is both the logical implication of a lifetime of work documenting the evolution of the physical self and a dramatic leveler that brings judgment on those artists who contend for canonization as great artists. If it weren't, Wilson might likely never give a second thought to documenting her aging body as she does.

It is also the expectation that a viewing public projects onto the auto-pictorial artist, the best of whom today happen to be women like Wilson--Cindy Sherman, Eleanor Antin, Adrian Piper, Mariko Mori. They, by the continuity of their photographic self-immersions, compel us to expect the process of the photographed life (even when entering the realms of the fictitious and mythopoetic) to play itself out to the end. The truth is, Wilson's project does invite us to want something existentially more of her after this.

The majority of the seven artists in Harris' Crazy Lady group show also showed personal insight into the psychological injuries of aging and the psychoneuroses that arise out of it, though the lesser work fell back on facile clichés.

Thankfully none relied on the kind of over-the-top psychopathology that Hollywood offers in place of real insight on the pain of the aging woman or the ostracized "crazy lady." There were no bunny boilers like Alex Forrest, the character played by Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction, and no beaver flashers like Catherine Tramell, the character played by Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct. And with regard to age, there were no ratched fiends like Minnie Castevet, the character played by Ruth Gordon in Rosemary's Baby. It was the first good sign that we're interfacing with artists who have real-life parameters in their sights for depicting the signage of authentic neurosis and psychosis. But it also implies that the focus of this show pivots around the populations who find themselves outside the instututional imperative of categorizing sanity and the norm while suffering the often permanent stigmatization of falling outside such categories.

The matter-of-fact, if self-deprecating, humor of Martha Wilson's photo essays on aging also permeates the staged eccentricites and medicinal allusions characterizing the better part of the Crazy Lady show. Even the renderings of immobile and catatonic 19th-century women hysterics in Lordan Bunch's Det Syke, are rendered in a realism that invites our empathy.

In Harris' show we linger over a video by Kathe Burkhart that gives us painfuly candid glimpses of a woman freshly spurned and incensed as she interviews the "other woman" with whom her ex-husband had an affair--itself an act that many might conventionally deem "crazy," as meaning obssesive. It's a brutally frank indictment of the entire XY chromosome race through the testosterone sins of the miscreant husband. Meanwhile Burkhart and her subject not surprisingly form a bond of sisterhood before our eyes in their shared malignment by duplicity. Such alliances have been made to seem dangerous and crazy. Women commiserating have been made to seem dangerous and crazy to the parties who would stand to lose by it.

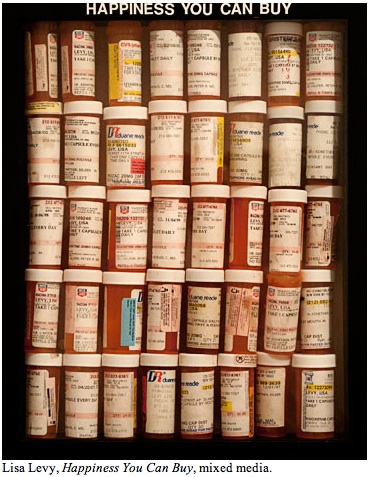

Lisa Levy, on the other hand, sees the XX chromosome to be no less culpable of reducing women to the cliches outlining the crazy lady. In her real-televised appearance on The People's Court, I had a difficult time determining who was the crazier lady: Levy the defendant, the elderly plaintiff, or the manic judge. In other photographic displays of over self-indulgence, Levy's lens is directed at women who callous over their loss of beauty and love with ostentatious eccentricities. Levy shows the least compassion for her sister subjects, staged as they are theatrically with herself Cindy-Shermanlike in the roles of the women she claims she fears becoming. But whether intentionally or inadvertently, we can see she looks down on such women. Of all the artists considered, Levy is the least self-reflective and the most maligned by her own eye.

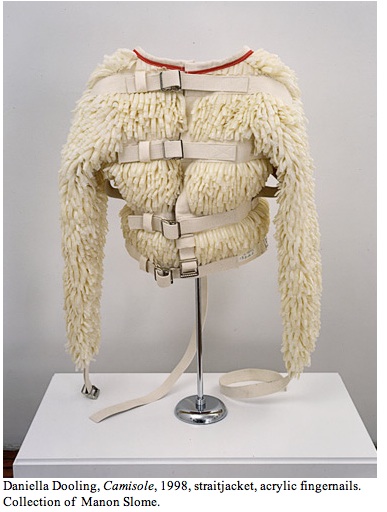

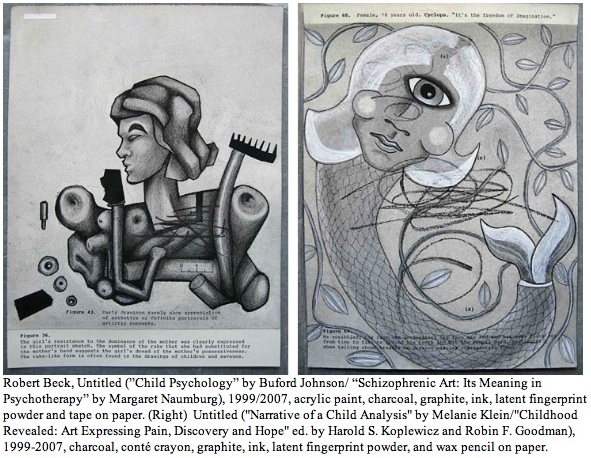

Robert Beck provides the most clinical and intriguingly insightful commentary with drawings after the psychoanalytic accounts of once-vanguard therapists like Melanie Kline, Buford Johnson, Margaret Naumburg, Barry M. Cohen and Carol Thayer Cox. Daniella Dooling films the acting out of psychotic fixations with the body manifested by compulsive rubbing and marking of the body with paints and other substances. Dooling also supplies the Crazy Lady show with it's centerpiece, a straight-jacket covered over with acrylic fingernails more than sufficing as a symbol of the obssessive fixation on commercial standards of beauty. Breyer P-Orridge supplies the only depictions of camp and transgendered subjects, but the bulging eyes, wigs and fake mustaches assumed by the artist effect a parody that, despite sending out slight signs of compensating for the painful disorientation of identity politics, void all authentic signage of distress because of the artist's burlesque approach to her subjects despite their unapologetic queerness.

Only Lizzi Bougatsos and Stephanie Snider leave us bereft of serious glimpses at women's instability. Bougatsos with photographs which have been outfitted with braces and overlapping eyebrows, the kind of object grafitti befitting adolescents; Snider with delicate silk panels that, apart from signifying princess fantasies, provide no access to the mind of the maker or the collector of such textiles.

Harris herself supplies evidence of wanting to mount a more ambitious theoretical exhibition around the crazy lady theme when she prefaces her press release with a quote from feminist authors Helene Cixous and Catherine Clement: "Societies do not succeed in offering everyone the same way of fitting into the symbolic order; those who are, if one may say so, between symbolic systems, in the interstices, offside, are the ones who are afflicted with what we call madness." It's an indictment that immediately compelled me to recall Monique Wittig's charge: "The discourses which particularly oppress all of us, lesbians, women, and homosexual men, are those which take for granted that what founds society, any society, is heterosexuality." In other words, heterosexual men defined the afflictions that depreciate human worth by having exclusively and historically comprised the populations of the institutions defining disease and criminality.

These and other feminists have shown the discourse of the human sciences--of psychology, sociology, anthropology, economy, legal and political theory--responsible for associating certain women's "eccentricities" (itself a term of suspicion in this commentary) with full-fledged pathologies. And for no other reason than that the predominance of hetero-male theoriticians and researchers in these fields over the last century and a half have entirely removed the subjects (women of age and facing life crises) from the direction and compilation of the psycho-somatic consensus defining their own categories and their own valuations. If democracy eluded women in the home and the workplace, it ostracized women inside the clinic, the hospital, the research lab and the academy.

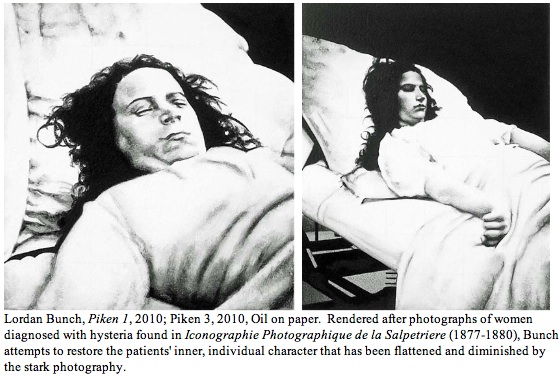

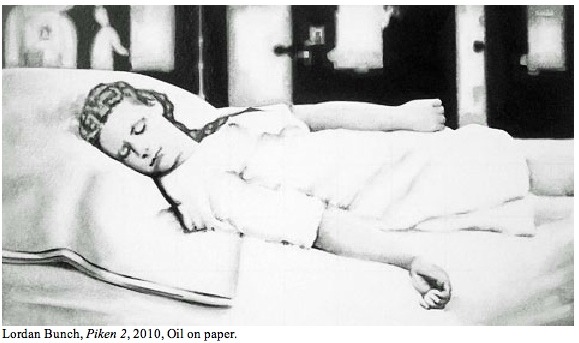

Ironically, it is work by a man that answers Harris's call for art evidencing the effects of male clinical prejudice. Lordan Bunch's "Det Syke," takes on the reprehensible signification of historical female hysteria in ink and oil renderings made after the photographs of women patients diagnosed with hysteria found in the publication Iconographie Photographique de la Salpetriere (1877-1880). Bunch attempts and usually succeeds at his project of humanizing the photographed patients. The pictorial advance is subtle but nuanced enough to make a difference. The women no longer appear as depersonalized objects flattened by the photographic medium and clinical setting. With Bunch's hand, we see, at times feel, the women's distress more clearly than their alleged psychopathology. We especially feel the distension of the women's faces, arms and hand muscles.

The renderings derive more power from their association with the redefinition of female hysteria from feminist perspectives, whether clinically or in cultural criticism. Psychologist Laurie Layton Schapira has redefined hysteria as in part aggravated when the accounts of the patient are dismissed or doubted. Feminist critic Elaine Showalter has gone so far as to claim hysteria as a root or first step of feminism--a kind of protolanguage of revolt communicating through the body messages that can't be verbalized, especially in a period of time when women (or that matter men) had no framework for signifying their often largely psycho-sexual repressions.

All three shows tease us by leading us only to the tip of the institutional and cultural iceberg still freezing economically disadvantaged women out of the defining consensus of diagnostics. It is also frustrating to see artists on the verge of remarkable thresholds of social and political artistic discourse holding back--especially after we have been privileged to the audacity of earlier generations of feminist artists--Frida Kahlo, Carolee Schneeman, Ana Mendieta, Lynda Benglis, Hannah Wilke, Kiki Smith--who made dramatically graphic strides in taking possession of women's self-representation despite the overwhelming opinion against them. After such rupturous artistic activism, except for Wilson and Burkhart, the women in these shows seem unduely cautious by comparison.

Yet, by comparison, Peggy Lee's pop performance of IS THAT ALL THERE IS? bristles from the tense undercurrents of emotional detachment being sent out to mitigate women's pronounced anxiety over their representative and sexual repression. Which is why, ladies and gentlemen, in leaving you I present the incomparable Ms. Peggy Lee singing what, in an era predating widespreading feminist ideals, was the common cry of women cut off from the vitality of their own self-realization.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.