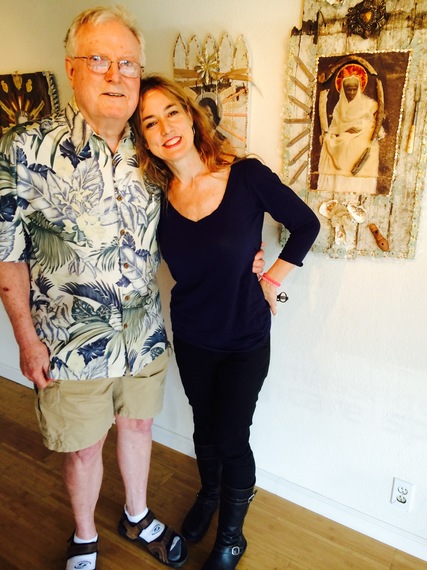

Five years ago, my talented and prolific father, Carson Gladson, was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease. As an established artist and lifelong pianist, having his perpetually steady hands become shaky was a devastating blow.

Not only was he depressed about losing his ability to play the piano, but, as the shaking increased, he also went through the gut-wrenching process of letting go of creating art, his love and profession since he was a teen.

When he was 19, he was approached by the Long Beach Museum of Art for a one-man show. He and his work made such an impact that the director and curator, as well as the handyman and receptionist, each bought a piece. He quickly was asked by the Municipal Art Museum in Los Angeles for another one-man show.

Never afraid of work and always willing to learn, he was well-respected by such artists as Bill (William) Brice and Norman Zammitt by his early 20s. Eventually, he worked as an art professor for more than 30 years. Being a professor gave him time to do his own artwork. But all that came to a screeching halt with his Parkinson's diagnosis.

The first time I saw his hands tremble at the piano, I had to fight tears. As he played a Gershwin tune (which he'd played impeccably all my life) for my older son (also an accomplished musician), his fingers betrayed him, and he stumbled. He was so good that most people wouldn't have noticed, but I immediately heard the slight trip-up, and had to bite down hard on my cheek so I wouldn't cry.

Moments later, masking his frustration so that my boys wouldn't see it, he moved to the yo-yo, a toy he'd handled like a pro. After a few repeat misses, he turned to my younger son (a yo-yo and Rubik's Cube master) and handed him the yo-yo, saying, "Well, you get the idea." My heart dropped to my stomach.

As the reality of his new life without the use of his nimble, steady and trained hands set in, so did a debilitating depression. I was terrified.

My usually cheerful, optimistic father was tumbling into a vortex from which I couldn't see an out. The two things that had sustained him throughout his life both financially and emotionally had been swiftly and mercilessly stolen from him. Each day felt like a monumental task for him to face. He was mostly catatonic, staring at his own gorgeous art on the walls, art that he thought he'd never be able to make again.

Then three years ago, he had an epiphany: He needed an iPad. He had survived a previous debilitation by turning to technology, and would survive and thrive somehow with Parkinson's too.

In the early 1990s, my dad developed carpal tunnel in his right hand. The hand that had gotten his work into the permanent collections of numerous museums, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Long Beach Museum of Art and the Oakland Museum, and displayed in banks, hotels, schools and private homes around the world.

He decided to check out Photoshop, and taught himself everything about the then-fledgling field of computer art. Carpal tunnel wouldn't stop him. Nothing would! This was Carson Lee Gladson. He made endless, innovative pieces on his desktop. He didn't stop or flounder. His flexibility was so inspiring to me.

After years of pushing through the pain in his hand, my dad began having horrible back pain. Following two harrowing operations (within days of each other) he began suffering dizziness, shakiness and depression.

Watching him struggle to get through each day in distress and a fog after his Parkinson's diagnosis was torture. Getting an iPad changed everything for him.

He began teaching himself art apps like "Brushes," "Drawing Brush," "Flowpaper" and "Procreate." After countless hours of passionate experimentation with these apps, he was making some amazing work.

Before long, he was sending me dozens of complicated and elegant pieces. I was beyond relieved, and proud. When he talked to tech support at Apple, even they didn't always understand how he was blending the use of multiple applications to get the effects he was getting.

My dad turned 75 last month and yet he has single-handedly taught himself so much and been so patient with both the tech and his own learning curve. I hope that others diagnosed with Parkinson's can be inspired by my dad's survival instinct, adaptability, drive and perseverance.

Equally important is the fact that without technology, my dad could have been lost forever in a downward spiral of depression. The iPad saved my dad's life. He is able to dive into each day anew, all because of this amazing piece of technology. Without it, I have no idea where he would be.

As I prepared for my recent gallery opening, I was able to text my dad shots of my work as I went along, so he could help me with decisions. We laughed because my instincts about the next move to make on a piece were usually right in line with his ideas. It was a luxury to have a seasoned art professor, art maker and my father at my disposal for each piece I made. I'm glad that, despite his illness, he can still be all of those things, thanks to a small device and his creativity.

Hope Demetriades is a Los Angeles-based writer and artist. Her latest mixed-media installation, "The North Stars: Canonizing the American Abolitionists," is traveling across the country.