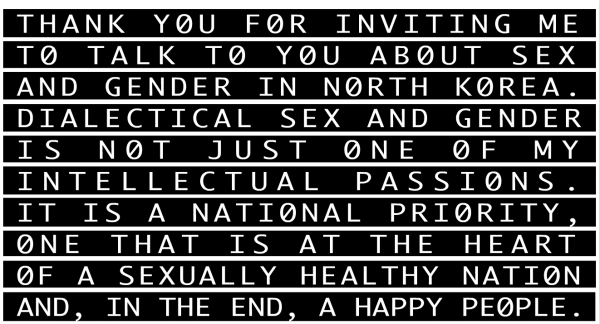

Still from Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries "Cunnilingus in North Korea"

This is the fifth in a series on "born-digital" literature.

Unlike conventional literature, which relies on sentence and word density, phrasing and transitional passages to alter narrative rhythm, e-lit can directly modify the reader's perception of time. This difference is due, in part, to the fact that conventional prose tends to maintain consistent fonts, page length and spacing. The physical act of reading is standardized, and, thus, narrative time is experienced conceptually rather than viscerally. Even today, works that decouple the visual and aural characteristics of language from meaning are considered "avant-garde" or, worse, "poetry," though there is, in fact, a long tradition of such manipulations.

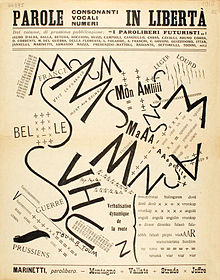

It was over a hundred years ago that Futurists Marinetti and Khlebnikov and Dadaists (Tzara, Schwitters) began experimenting with "pure sound," fonts, text placement and collage.

"Après la Marne, Joffre visita le Front en Auto" (After the Marne, Joffre Visited the Front by Car), by Marinetti, 1915

In the 1960s, William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin literally cut and pasted sections of text to create prose and poetry that radically altered narrative rhythms. In the 1970s, writers like Robert Coover, Raymond Federman and Italo Calvino offered further innovations. As computer technology improved, a range of techniques became available to writers. The earliest e-lit example is hypertext where links lead the viewer circuitously through a story in which each fragment can function as its own mis-en-scene. More recently, Young Hae Chang Heavy Industries (artist Young-hae Chang and poet Marc Voge) utilize simple flash animation to create graphically arresting narrative poems. In their work, the inherent musicality of language interacts with the rhythm of the sound track. Moreover, the use of animation adds an additional rhythm, a visual one that competes with the musical score. The duo manipulates the rate at which words appear and disappear and the size of the words themselves thus altering how they are received and processed.

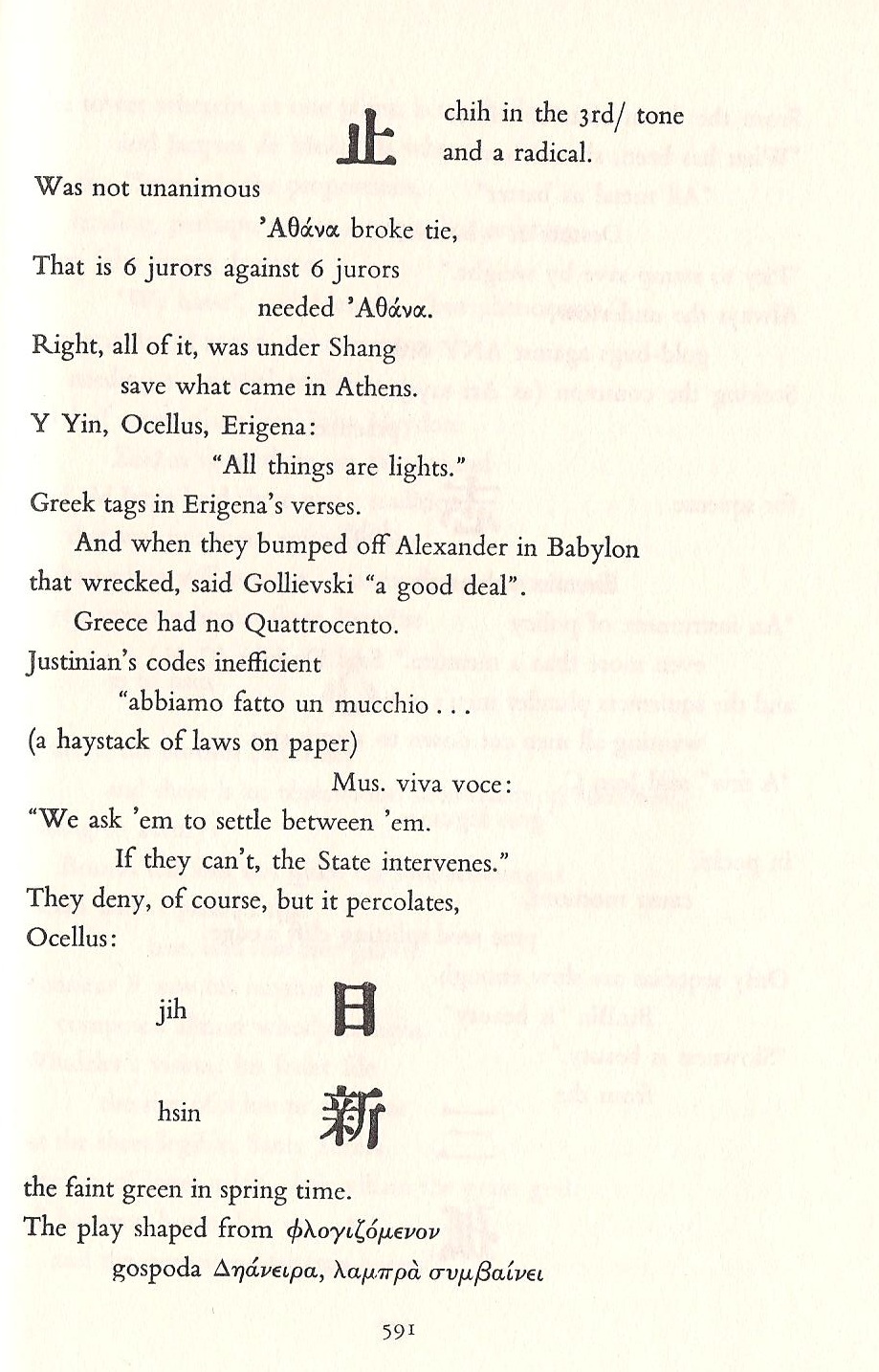

In a recent offering, "Dakota," inspired by poet Ezra Pound's first two Cantos, Odysseus' journey to Hades is transmuted into a nightmarish, beer-soaked, fly-over-state road trip. At fist glance, this piece seems to have little relationship to the modernist masterpiece. It is only in considering the Cantos as a whole, with Pound's use of Chinese ideograms and multiple languages, that the resonance of both with cinema becomes apparent. In fact, YHCHI makes this linkage overt with their opening sequence countdown.

From "Canto LXXIV" by Ezra Pound

According to philosopher Gilles Deleuze, the revolutionary change in film occurred when the "movement-image," a progression of "privileged" instances of action and reaction, was replaced with direct perceptions of lived time and "any instance whatever" which are strung together by the cut. Like Eisenstein's "montage of attraction," the Cantos combine images, ideas and symbols to produce affective and intellectual responses. In "Dakota," reading is transformed into a multi-sensory experience of competing rhythms which interact like waves, amplifying and diminishing each other. Sometimes, content and meaning are completely sacrificed to time as the text comes too fast for the reader to read, let alone use to construct a conceptual image.

Writer Burroughs, himself, experimented with film. In The Cut Ups (1966), a voice-over narrator intones the banal words "hello" and "yes" over spliced images. More recent visual experiments in narrative rhythm include Jenny Holzer's animated LED signs in which she utilizes the rapid pacing of advertisements to "sell" subversively humanitarian political messages, and Christian Marclay's videos.

In "Quartet," Marclay projects fragments of Hollywood films on four screens sacrificing much of the the visual and narrative content of the films to produce a single tour de force soundtrack. (See also his brilliant piece "The Clock.") As suggested by these examples, it is unsurprising that YHCHI's work has been distributed both as e-lit and as visual art.

I asked them about this:

Your work is considered to be electronic literature and visual art. It is shown in museums and is also freely available on the web. When you were starting out, did you make conscious decisions about how to distribute this work (as "new media" art) or was it just a matter of finding open channels?

We did indeed set out to reinvent poetry and art -- no, check that. We set out to prove that the future of poetry and art was on the web -- uh, not quite, either. In truth, we basically set out to do something on the cheap, and a computer and a 28K modem, a domain name and a $10-a-month web plan seemed to give us the biggest bang for our buck. We were living in a galaxy far, far away (Seoul, South Korea), a real backwater back then, and we bought into the idea of the World Wide Web and the Information Superhighway. Sounds quaint now, but we were idealists. It's funny, though, because although we're still in Seoul, you're in Washington D.C.(?), and we can now e-mail a Huffington Post link to our mothers elsewhere in the world. Beautiful. Thanks for giving us this chance.

Can you speak about how you started working together and how the collaboration works -- division of labor, editing, distribution, etc.?

It was pretty simple. We figured two mediocre heads were better than one, and got lucky, since creating text in the art world doesn't abide by the same rigorous quality controls as writing in the literary world. Marcel Duchamp demonstrated this a hundred years ago in his work "The." Here was a guy right off the boat who had no trouble creating and passing off an English text as an artwork.

At first we created one text in Korean for every text in English, but quickly discovered that no one was paying attention to our Korean texts. So now we just write in English with, every few years, the odd French text. Others have translated our English into the 20 languages we've been transforming into art.

Although our early works are set to famous jazz tunes, for many years now we've been making our own music. We bang on drums and computer keyboards, blow into plastic instruments and, through the miracle of the digital age, the sounds turn into a kind of music. Again, we're lucky, because as with text, art doesn't hold music to the same high standard that music holds music to. We don't edit much. We just speed things up so you don't catch our mistakes.

What I love about this work is how the graphics and soundtrack reveal the power of language -- language as visual characters on a "page" and spoken language as sound. How do you think that the move toward digital means of communication has altered our relationship to language. Do you think your work addresses that?

Maybe. And thanks for the love. We don't think much about graphics. We always use the same font, and we almost always use the same color. Because of e-mail and texting, people today are reading and writing more and more, and they're reading and writing more and more bad stuff. And they're reading and writing it very quickly. Our work sort of fits into this zeitgeist. The funny thing is that this doesn't bother us, because, well, 99.9 percent of all art is deemed forgettable, so why not the same percentage of reading and writing?

Poetry has a long tradition of combining graphics (typeface/pictures especially Futurism, Dada, etc.) Has your work been accepted in the conventional poetry community as poetry? Has it been presented, performed or shown as a form of poetry?

Our work is studied, it seems, in English and other campus departments. We've even had the pleasure of presenting our work to some of them. But accepted by the conventional poetry community? We hope not.

I had a conversation recently with poet Lou Asekoff about poetry as "embodied knowledge" that is to say, a visceral experience -- we feel poetry, we don't think it. Your use of animation and soundtrack contribute to this kind of experience. Do you have any thoughts on that and what role poetry can play in an increasingly virtual world?

We agree. Ideally, poetry should be felt first, thought second. But, at least these days, it isn't, and that's why it's become isolated and insignificant. What we all feel the most today is music, which is why it was a no-brainer for us to sync text to music. We'll take all the help we can get. As for the future of poetry, it looks pretty bad unless you consider its future to be rap.

The work that I'm familiar with tells a story of some sort -- have you experimented with more fragmented or abstract kinds of text? Why or why not?

We like to think we're all about content, and when it comes to our style, content is already disjointed enough. The abstraction is in the digital, animated medium. We also like to think we're the opposite of interactive texts. We've always found interactivity -- clicking from fragment to fragment -- to be unsatisfying. We don't mind saying that we're closer to YouTube than to Mallarmé's "Un Coup de Dés."