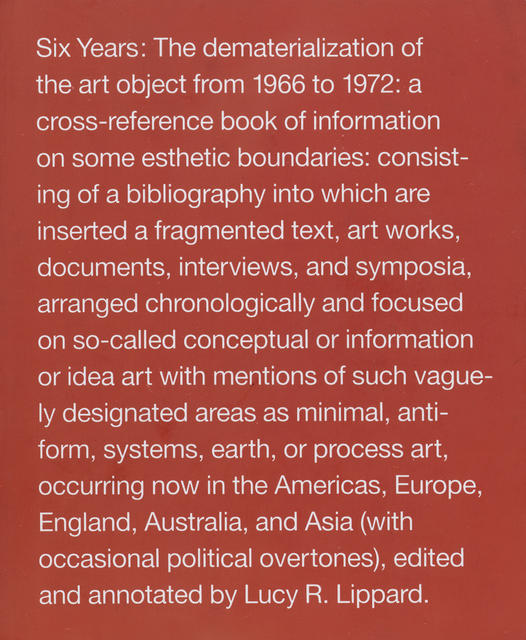

Almost willing the project into the annals of marginalia out of which it came (the title alone seems an exercise in refusal), writer-curator Lucy R. Lippard never expected anyone to really read Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object From 1966 to 1972, a cross-reference book of information on some esthetic boundaries: consisting of a bibliography into which are inserted a fragmented text, art works, documents, interviews and symposia, arranged chronologically and focused on so-called conceptual or information or idea art with mentions of such vaguely designated areas as minimal, anti-form, systems, earth, or process art, occurring now in the Americas, Europe, England, Australia and Asia (with occasional political overtones), edited and annotated by Lucy R. Lippard. As she confesses in a revised author's note accompanying the University of California's 1996 reprint of the 1973 book, by then a collector's item: "When it [first] appeared, I was amazed to hear that some eccentric souls were unable to put it down, and a lot of people seemed to be plowing through it, plugging into the hidden narrative that I thought would be an involuntary secret."

Front cover of Six Years: The dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972..., 1973, Paperback book, 8¾ x 7½ in. New York and London: Praeger Publishers, 1973; second edition, with a new introduction, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996

The art world in 1973 was obviously a very different animal than it is today. Its emerging institutionalization (the first Whitney Biennial was held, and Art Basel, only three years after its founding, superseded Cologne as the largest art show in the world) paralleled a momentous political year when Nixon released the Watergate tapes, the Vietnam War officially ended, Roe v. Wade was passed, AIM (American Indian Movement) seized Wounded Knee, and OPEC doubled its prices, among other notable events.

Eleanor Antin (American, b. 1935)100 Boots Facing the Sea, Del Mar, California. February 9, 1971, 2:00 p.m. (mailed: March 15, 1971), 1971-73Photograph8 x 10 in (20.3 x 25.4 cm)© Eleanor Antin. (Photo: Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York/www.feldmangallery.com)

That it was the feminist vanguard which led the fray at this time (Judy Chicago's book, The Flower, was also published that year, and Woman's Building, a radical redress of patriarchal education, opened its doors then as well) is as they say, herstory now, quite literally, as the pivotal role of women artists in the emergence of everything from body-based performance art to institutional critique is still often relegated to the footnotes of art history. Outside the (much debated) historicizing of 1970s feminist art in the mid-1990s when many male artists -- Mike Kelley, Oliver Herring and Jim Hodges, among them -- began to appropriate its strategies, using craft-based processes to undermine the same high-low art divide their female predecessors (and in some cases, teachers) straddled decades before, the conceptual underpinnings of feminist art and its far-reaching consequences has been largely ignored in the museum world. Until now.

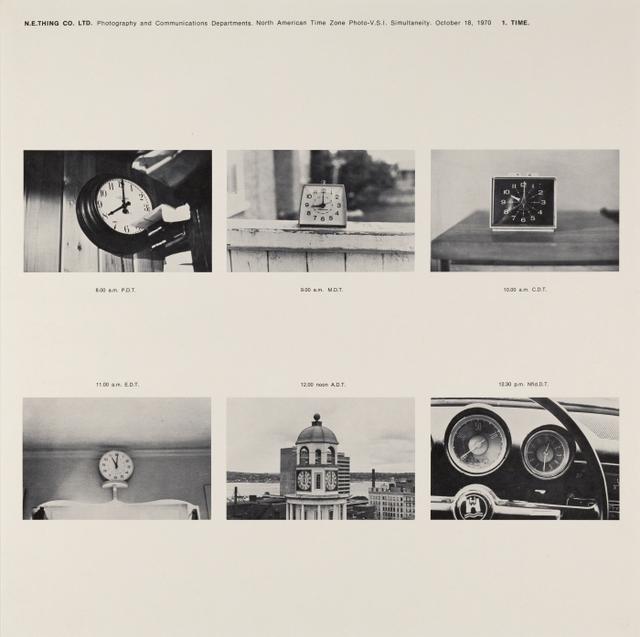

N. E. Thing Co. (Iain Baxter& [Canadian b. England, 1936] and Ingrid Baxter [American, b. 1938]) 1. Time., detail from North American Time Zone Photo-V.S.I. Simultaneity, October 18, 1970, 1970 Offset lithograph,17½ × 17½ in (44.5 × 44.5 cm) Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver; Gift of Iain Baxter and Ingrid Baxter, 1995

Taking Lippard's book as an experimental call to action, Catherine Morris and Vincent Bonin, the curators of the Brooklyn Museum's exhibition,Materializing Six Years: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art, resurrect this "herstory" in the most innovative way, reconnecting the dots, and putting pedal to the medal in an effort to make up for lost time. Wanting to know more about the intentions behind this historically significant, conceptually innovative exhibition, which recently closed on February 3, I interviewed them hoping to gain better insight into their curatorial vision, and its implications for future programming while also foregrounding the contributions of one of the most important and seminal feminist figures in art, the great Lucy R. Lippard.

JH: When the Sackler Center honored Lucy Lippard as the first feminist art critic at its first awards event last spring, the exhibition, Materializing Six Years: Lucy Lippard and the emergence of Conceptual Art, was presumably already underway (museums schedule exhibitions years in advance). What was the original inspiration for turning this seminal book into an exhibition?

CM-VB: The inception of Materializing Six Years goes back more than five years to speculative conversations we started having about how the book -- which we had both long admired -- might function as an armature for an exhibition. In 2007, we called Lippard to see what she would say about us turning our idea into reality. After some initial resistance (mostly having to do with the fact she was -- and continues to be -- more interested in her current work than revisiting what she was doing 40 years ago), she encouraged us, but also wondered how we would compress this very complex narrative into an exhibition space, and where we would "find" works that did not always have a physical form (or may not have survived). These became some of our challenges.

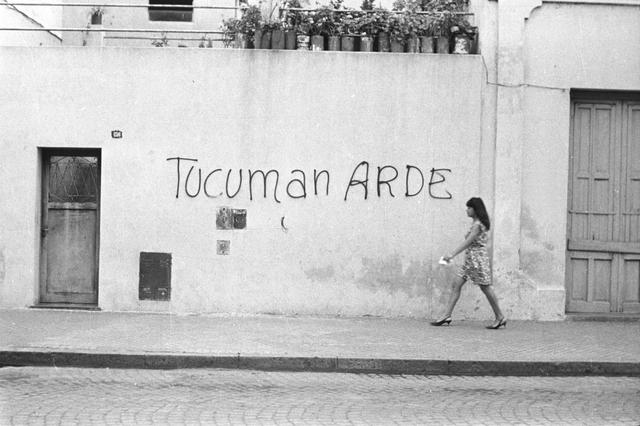

Rosario Group, Tucumán Arde (Tucumán Is Burning) Publicity Campaign (2nd Step), 1968, Graffiti, Archivo Graciela Carnevale, Rosario, Argentina © Grupo de Artistas de Vanguardia (Avant Garde Artists Group). (Photo: Avant Garde Artists Group)

Six Years was written during a time of political unrest and at the crossroads of many changes in the artworld. Lippard was herself involved in groups that advocated reform of institutions (some of which are mentioned in Six Years). Interestingly however, she did not emphasize this burgeoning politicizing in her book. Rather, she left the reader free to decipher it in between the lines. What she called a "hidden narrative" or described in the last parenthetical part of her title, as "(with occasional political overtones)" became an element that we wished to make perceivable in our exhibition. But we did not want to impose a revisionist approach on the material at hand, hoping instead to underline those elements we saw as latent in the book. During the process of selecting the works/documents, we always tried to be as straightforward as possible.

Installation view of Benefit for the Student Mobilization Committee to End The War in Vietnam including works by Will Insley (left) and Jo Baer (right); Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, October 22-31, 1968; organized by Lucy R. Lippard, © Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. (Photo: James Dee, courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York)

We also wished to show how Lippard's understanding of conceptual art was very hybrid and speculative: it included works in different mediums that eschewed the linearity of a well-known art historical narrative (starting with minimalism and ending with analytical conceptual art in the vein of the art and language collective). Alongside the representation of the more trenchant positions of its well-known protagonists, she championed some works in which playfulness, affect, as well as ideological ambivalence, where put to the fore.

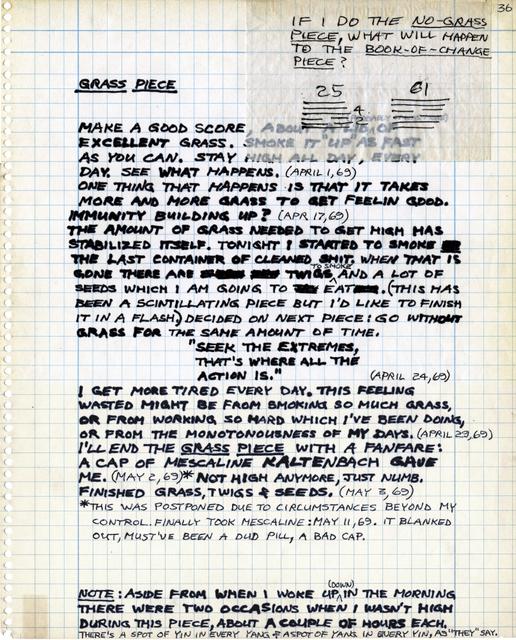

Lee Lozano (American, 1930-1999), No Title (Grass Piece), 1969, Graphite and ink on paper, 11 x 8½ in. (28 x 21.5 cm), Collection of Alan Cravitz and Shashi Caudill, Chicago © The Estate of Lee Lozano, courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Zurich

The only manifest "corrective" aspect of the show is perhaps its emphasis on the overlooked role of women artists within the movement, by the inclusion of an epilogue on the last number show: the exhibition entitled c. 7500 (1973-1974), devoted solely to women artists that happened just as Six Years was being published.

JH: The show is as much about conveying the trajectory and import of Lippard's career/contribution as it is "materializing" her book, representing a desire to "demonstrate how her curatorial projects, critical writing, and political engagement helped to redefine exhibition-making, art criticism, and the viewing experience." Other than through examples of work/artists she collaborated with and curated, how else did you attempt to convey Lippard's legacy in these terms?

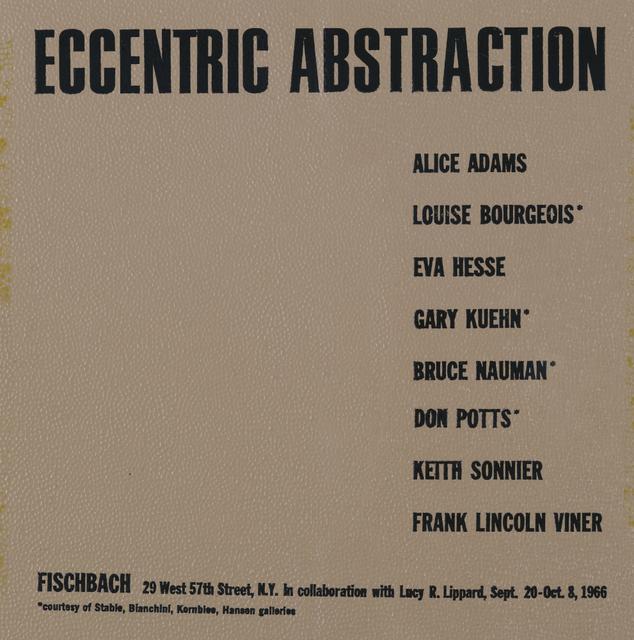

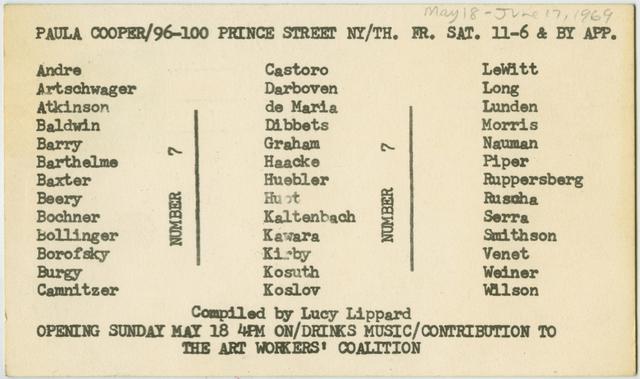

CM-VB: From the earliest phase of researching and gathering the archival materials/selecting the works, we decided that Lippard would not be the focus of our project, but rather one of its (important) protagonists. Lippard herself endorsed our choice, as she told us many times that she wished the exhibition to be about the book and not about her. We nevertheless focused on some of the exhibitions she curated (and which she included in her book -- Eccentric Abstraction, 1996, and the famous "number shows,"1969-1974, for instance) as one structuring device for the exhibition.

Announcement card for Eccentric Abstraction, 1966,Printed text on vinyl, 6 x 10 in. (15.2 x 25.4 cm), © Fischbach Gallery, New York

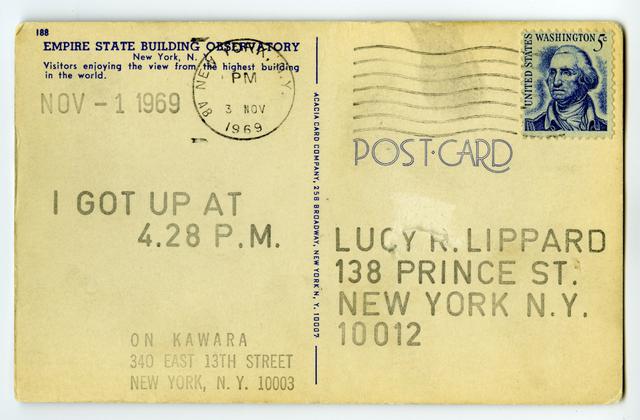

The difficulty was to make her presence felt within this narrative while focusing on the book as the main object of study. One strategy for this was to foreground the importance of colleagues with whom she entertained a vivid dialogue through these years (Seth Siegelaub, Sol LeWitt, On Kawara, N.E. Thing Co., etc.). We did so by showing works/archival materials pertaining to the collaborations that she initiated with many individuals. Along the way, we also addressed the broader back-and-forth exchanges that happened between curators, critics and artists at the time.

On Kawara (Japanese, b. 1933), I Got Up, November 1, 1969, 1969, Postcard, 4 x 5 in. (10.2 x 12.7 cm), New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe; Gift of Lucy R. Lippard, © On Kawara. (Photo: New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe)

Amongst a number of other critics of this period, Lippard was perhaps the one that went the furthest in expanding the traditional definition of writing about art and of curating, at the expanse of sometimes being accused of trying to be an artist in her own right. The emphasis on collaboration and the questioning of authorship led ultimately to her active and well known engagement with feminism in the seventies and eighties. One of the most important legacies of Lippard's oeuvre is the often overlooked link between the development of conceptual art and the strategies visual artists developed to address social and political concerns that were emerging simultaneously -- civil rights for women, African Americans and gays and lesbians.

Installation view of the exhibition Materializing Six Years: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art

In some sense, we have come to see the phrase "the personal is political" as being as much about conceptual thinking as about feminist activism. We think in many ways Lippard's work was an important link between conceptual art and political activism, as we understand it today. It is important and interesting to note that in 1973, these links were not clear. It took later artists collectives like the Guerrilla Girls, Group Material and ACT-UP, amongst others, to make these links clear.

JH: Much of the art presented is text-based and archival, emphasizing process, systems, information, events, etc. over form, its political import deriving largely from an anti-commercial, anti-material stance. In her essay for the catalog, Lippard describes the latter as one of the biggest influences of this pivotal phase in the emergence of big-C conceptual art: "These artists invented ways for art to act as an invisible frame for seeing and thinking rather than as an object of delectation and connoisseurship. Its most subversive aspect -- institutional critique that happened within the art itself, in its form rather than its content -- is among its most important legacies." That these works were brought together in the form and context they once summarily rejected is ironic, and yet inevitable if the show was to go on. Was this an issue for you, and how did you attempt to address/reconcile this contradiction?

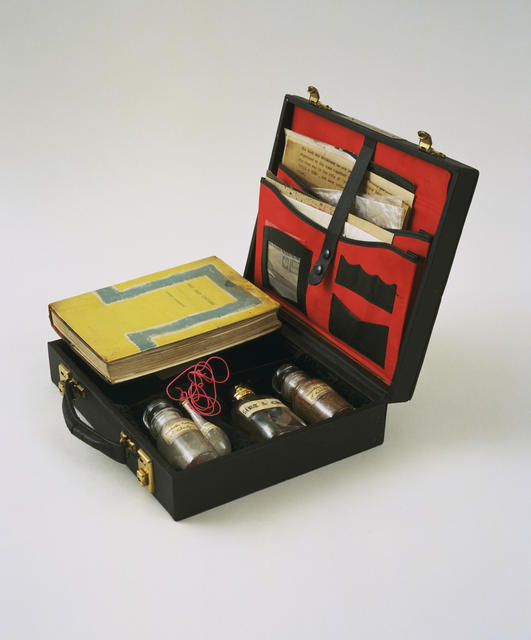

CM-VB: If one of the great "failures" of conceptual art is that it was readily and largely easily subsumed by the market and institutional system of the art world which it sought to, at least circumvent, if not completely overthrow, Lippard thought it's bigger failure was it's lack of successful engagement with a broader public audience. Some conceptual artists did leave the art world as they saw their work becoming part of the gallery system, but in the first years of the movement, most wanted to participate in the art world, just on different terms. Think of John Latham's Art and Culture, which is one of the pieces that opens the show, it is a very hermetic, inside-the-art-world piece (though also funny and self-conscious) and at the time, Latham wanted to have a conversation with the art world. In fact he seemed to want to simply get Clement Greenberg out of the way so he could make a different kind of art.

John Latham (British, b. Zambia, 1921-2006), Art and Culture, 1966-69, Leather case containing book, letters, photostats, and labeled vials filled with powders and liquids: case

3⅛ x 11⅛ x 10 in. (7.9 x 28.2 x 25.3 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund, © 2011 John Latham (Digital image: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY)

In term of our own curatorial endeavor, we made an effort to provide clues to the viewer so he/she can understand the complexity of these art practices. While the exhibition is demanding -- a lot has to be read and contemplated -- we believe that it remains accessible. But to answer your question: yes, showing the remnants of dematerialized art in a museum could be seen as the ultimate demise of the utopian potential that Lippard ascribed to the works at the end of the sixties. (And it is worth noting this demise was seen as coming very early on by Lippard and others.) However, these works are now available to viewers in their complex materiality -- they take room, have a form that published documentation doesn't convey, and they also interact with each other within one space. There is a loss and a gain of meaning. We also displayed a number of archival documents that demonstrate how these works circulated among a network already partly enmeshed in the commercial art world, and also on its fringes (as the era saw the birth of many alternative spaces and structures).

Announcement card for Number 7, 1969, Printed card, 3 x 4 in. (7.6 x 10.2 cm), © Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Perhaps the point is to clarify that these utopian aspirations did not fail completely, but were partly realized. In many of the projects exhibited as well as in Lippard's work as a curator and political activist, there is a pragmatic approach mixed with idealism that can continue to inspire us today. The contemporary art world, with all of its paradoxes, consolidated itself during these six years. Much has changed, but also much remains the same.

JH: I love the density of works on view, the unpacking that accompanies their anti-authorial intentions and reading. For me it was a treasure trove from a time when the art world was small enough to matter (ala Nancy Holt's crossword puzzle of who's who in the downtown scene -- including two words that Lippard "used to mean eccentric": "off center" ), and people still believed that art could revolutionize society. Perhaps it was the last gasp of the utopian model, as you suggest, which reminds me of an interview I did with Warhol superstar, and photographer, Billy Name, who insists that all art today is derivative of this period, especially the decade of the 1960s. Why then I wonder are so many dismissive of its impact, its anti-material stance, etc.? What are your thoughts on this?

Vito Acconci (American, b. 1940), Following Piece, 1969, Activity, 23 days, varying times each day; typewritten statement, 11 x 8½ in (27.9 x 21.6 cm), Photographic negatives: Acconci Studio; archival documents: Ilona Rich, Brooklyn, © Vito Acconci. (Photo: Betsy Jackson, courtesy Acconci Studio, New York)

CM-VB: In many ways, we were driven by Lippard's anti-authorial approach, which leaves the viewer on his/her own to navigate the complex relationships between the materials that she gathered in the book (although we provided some necessary didactic framework). The amazing energy the book still retains is, we believe, largely derived precisely from Lippard's lack of critical distance -- from her personally engaged and expansive exploration of what she saw going on. As we mentioned before, our methodology was deliberately straightforward: gathering works that would give some kind of overview of what she attempted to map, and trying to stay close to her project. However, it was impossible not to add our own perspectives on the era, as they emerged from our own historical perspective of the book, which were largely taken up in the catalogue. One of the most important hidden narratives in the book, which we attempt to highlight, was the difficulties women artists had in showing their work, and being taken seriously by the commercial part of the art world. Christine Kozlov, Lee Lozano, Adrian Piper, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Martha Wilson and many others were active participants in the mostly private discussions that defined conceptual art at its inception, but until recently, their presence was overshadowed, ignored and even excised.

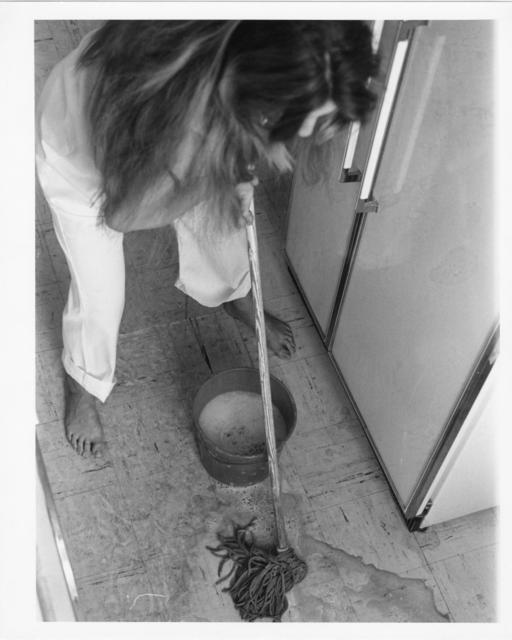

Mierle Laderman Ukeles (American, b. 1939), Private Performances of Personal Maintenance as Art, 1969, Black-and-white photograph 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm); later reproduced as contribution to the catalogue of c. 7,500, Index card, 4 x 6 in. (10.2 x 15.2 cm) Valencia, Calif.: California Institute of the Arts, 1974 © Mierle Laderman Ukeles. (Photo: Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York/ www.feldmangallery.com)

As the work of the late seventies and early eighties would make clear, all of the strategies defined by conceptualism expanded through feminist rereading. We hope this point is touched upon throughout the exhibition, culminating in the epilogue which documents Lippard's conceptual art exhibition devoted to women artists, c.7,500.

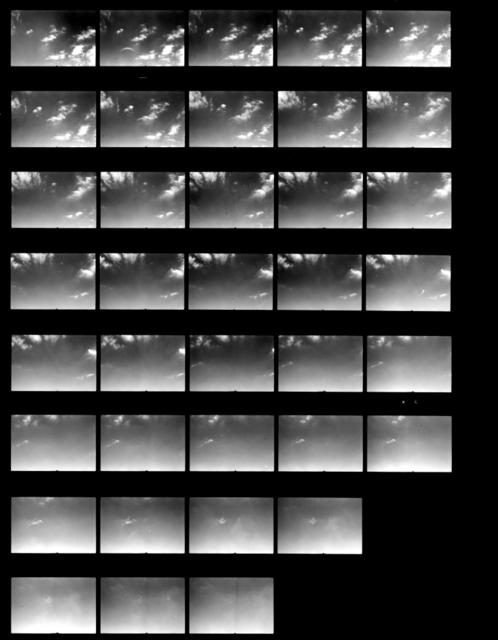

Alice Aycock (American, b. 1946). Segment of Cloud Piece, 1971, One of five black-and-white photo contact sheets, 21¾x 15¾ in. (55 x 40 cm) each,© Alice Aycock. (Photo: Alice Aycock)

JH: Simultaneously, the show is full of ephemera recreating or recounting early (often forgotten) works by artists who are now famous/canonical, from Robert Morris's work, "Steam," 1966, to Richard Long's "Sculpture for Martin and Mia Visser," 1968. Reflecting the contents of the book, but also maybe the degree to which the oeuvre of male artists are still more highly regarded and consequently preserved? Did you find it easier to access works by such male artists? And will the precedence of their inclusion into a program whose mission is to promote women artists like the Sackler Center be reflected in future programming (i.e., would you consider including men again)?

Installation view of the exhibition 955,000 including construction made following instructions provided by Richard Serra; Vancouver Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, January 13-February 8, 1970; organized by Lucy R. Lippard

Vancouver Art Gallery Archives. (Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery)

CM-VB: The fact is that Six Years chronicles discussions Lippard saw happening during this period, and as documented, they were often largely between the male protagonists of the movement. But our show opens with work by Louise Bourgeois, Alice Adams and Nancy Holt, putting women at the forefront of the movement. In addition to the canonical male names, we also worked to emphasize lesser-known figures that lived outside of the main art world centers of the time, as well as some more obscure manifestations of conceptualism that Lippard included. We did set ourselves a goal of including work that challenged canonical readings of the genre.

Installation view Materializing "Six Years": Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art

The good news is that we didn't find it easier to access the work of the better known male artists. In that sense, you could say the research and development of the checklist was remarkably egalitarian.

The opportunity to present a lot of male artists -- most of them not particularly known for their feminist activism -- is a significant part of this project. The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art is an exhibition and program space committed to looking at visual culture through the lens of feminism and it impact over the past forty plus years. As the name indicates, it is not a center for women's art. Feminism is not a gender specific designation; it is a method for critical examination of any form of human production. The chance to point out that Lucy R. Lippard played a vital role in defining the parameters of this particular movement and is one of the people who challenged conceptual artists to examine the politics of what they were doing is very much what we strive to do.