Look, I don't want to raise your anxiety level, especially as you're nursing that headache from last night's revelry. But I figure you'd want me to give it to you straight, starting out the new year by cataloging a few of the risk factors in play, economically speaking.

Europe: As the countries of the Eurozone continue to slowly and bumbly work through their debt problems, contagion remains on everyone's list of things to worry about. The contagion channel is mostly through financial markets, though the fact that the EU is the recipient of about 20 percent of our exports means that an export-dampening recession will hurt too.

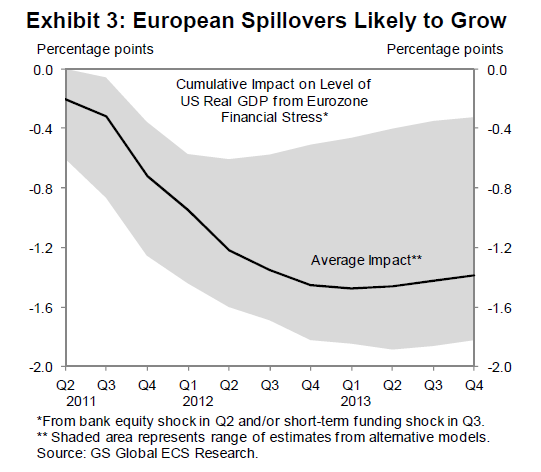

How much hurt? The researchers at Goldman-Sachs provide the figure below. Europe could subtract around a point from real GDP growth next year. That's half-a-point higher unemployment, hundreds of thousand fewer jobs, etc... and those are some headwinds we really don't need right about now.

But what's noticeable in the figure below is the wide-and-getting-wider error margin around their best guess.

So, which way might this bounce? I wouldn't be surprised if the right answer is the less-bad part of the shaded area in the figure. One key to the resolution here has been the ECB accepting their role as lender of last resort, ramping up the loans to member banks, who can then buy sovereign debt, leading to lower yields, and ultimately, the ability of the troubled countries to service and rollover their debts without cracking up.

What changed? That summit a few weeks back, which many said didn't deliver much, actually appears to have moved the ECB. By agreeing to put restrictive fiscal measures in their individual constitutions, as opposed to the over-arching -- and ignorable -- rules of the Maastricht Treaty (fiscal rules that Eurozone members were supposed to adhere to, though virtually none did so), the central bank appears to have been mollified. I'm not saying that's good policy -- such rules can lead to damaging, austere macroeconomics, though of course it's not clear the new rules will work any better than Maastricht.

But what matters now is that they've helped get the ECB back in the game, so mark this one down as a real risk factor, for sure, but one with perhaps less downside risk than the conventional wisdom would suggest.

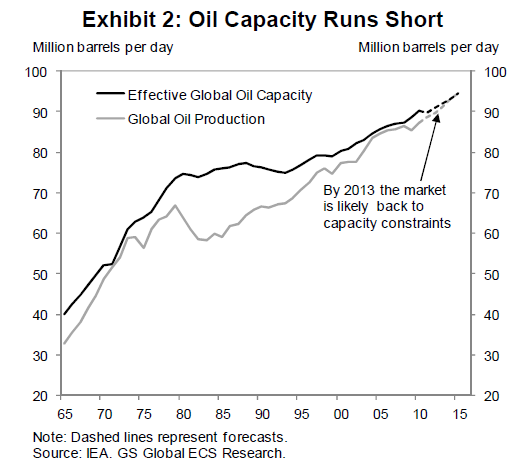

Oil: On the other hand, you don't hear enough about this one. Global supplies are tightening, and under those conditions, it doesn't take much at all to generate a price spike. The GS folks have a figure on that too, showing global production catching up to global capacity.

My gut is that there's downside risk here. Most people's paychecks are already lagging inflation -- i.e., falling in real terms (see penultimate graph here) -- and faster inflation due to a spike in oil won't help.

Labor Force Participation: This one's a sleeper and much less discussed. It's a mixed bag, but here's the concern.

One reason the unemployment rate has fallen as much as it has -- and it hasn't fallen enough -- is because fewer people are in the job market looking for work (remember, you're not counted as unemployed if you're not actively looking). If the pace of job growth begins to improve, that's likely to draw these sideliners back into the game, and that puts upward pressure of the unemployment rate.

Like I said, it's mixed, because the scenario I'm describing includes faster job growth (good) but higher unemployment (bad).

I've crunched some numbers on this -- I'll post the analysis later, maybe -- and I found that if the pace of recent job growth continues, around 130K per month over past six months, the rate of labor force participation might stop falling, but would probably remain flat. But if we start hittin' it in the 230K range, it should start to grow, making it tougher, even with extra job growth, to bring down the unemployment rate.

I've left off the biggest threat of all -- irresponsible policy makers ignoring all of the above, and failing to do their jobs on the economy, either because they'd rather hurt the President than help working families, or because they simply don't get the need for more temporary stimulus...or because they do get it, but irrationally fear budget deficits. As I've said ad nauseam, it's not the temporary stuff that hurts you on the deficit.

Of course, there's the possibility that during the holiday break, the scales have fallen from their eyes and they now understand the Keynesian imperative of the moment. For odds on that possibility, see here.