Had a rousing debate on inequality last night with Scott Winship from Brookings, moderated by Reihan Salam, both of whom lean conservative, and both of whom brought generally interesting and provocative views to the discussion.

The conservative take on the issue tends to fluctuate from mild denial (Winship, not Salam), to which I strongly object, to "is it really that big a deal?" with which I disagree but find interesting and challenging.

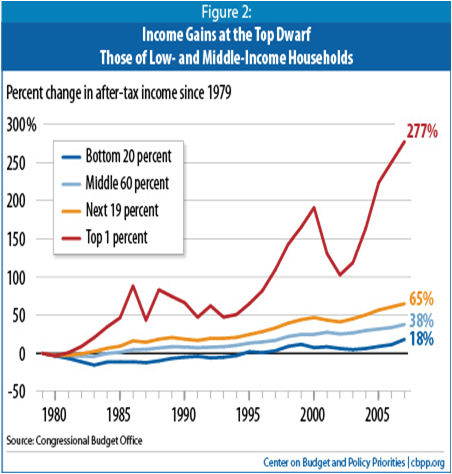

On the denial front, what you mostly get is the "if-you-just-adjust-it-this-way-or-that-way-it-all-goes-away." Scott raises immigration, incarceration, family structure, employer-provided health insurance, deflators, to name just a few. Some of these don't affect inequality, like deflators (although Scott cited research that finds prices grow more slowly for poor people); others cut "the other way" -- incarceration disproportionately takes lower earners out of the mix, so putting them back in would widen the gap between lower and middle-wage earners. Most of these are dealt with in the CBO data shown in the figure below, including health care, family size, taxes and transfer payments. So, yeah, there's a lot more inequality and forgive me if I won't swim in de-Nile on this point.

More interestingly, both Scott and Reihan raised questions about how much all this inequality matters.

The first argument is that there's nothing zero-sum about the rise in inequality. Romney's or Buffett's or Gates' or Zuckerberg's gains are not anyone else's losses. That's hard to accept, given that it's not just that most people's real incomes kept going up like they used to, just not as fast as those at the top. Income grew more slowly for middle- and low-income households and poverty rates were stickier (i.e., less responsive to growth) in times of rising inequality. The divergence of median compensation from productivity suggests that in the age of inequality, the typical worker is simply not capturing as much of their contribution to growth as was formerly the case.

In economese, some of what these and other rich guys and gals capture are "rents," which are not zero-sum. We see this most commonly in the growth of financial markets as a share of the American economy, an important factor in not just the growth of inequality but in the bubble-bust cycle that's done so much damage of late.

In the 2000s, the median income of working-age families stagnated and poverty went up, even as the economy grew and the capital-gains powered income of the top 1% soared (see figure). Since the current recovery began, profits have soared, inequality is back on the rise, and the pay of average workers has stagnated of late. My own longer-term analysis of the factors responsible for the diminished elasticity of poverty with respect to growth finds inequality to be the most important factor (see figure here).

The latter 1990s provides a very useful counterexample. With true full employment upon the land -- my favorite inequality antidote -- inequality actually diminished between the middle and bottom (the top continued to pull away -- cap gains, again), low wages grew with productivity for a New York minute, and poverty rates fell sharply. Inequality, at least in the bottom half of the wage scale, compressed and a lot more growth reached a lot more people.

Similarly, Scott doesn't buy that inequality negatively affects opportunity, despite all the arguments here. From that post, I keep coming back to this anecdote, because I think it's so emblematic of the problem:

...once you start looking for these linkages between inequality and opportunity, they show up everywhere. Here's a great example from this AM's WaPo, where public schools facing budget cuts--the disinvestment in public goods noted above--turn to parents to raise funds, and not for one-off trips to Mount Vernon, but for science curriculum, guidance counselors, smaller class sizes, music classes, etc. Of course, the affluent parents can raise hundreds of thousands; the poor parents, barely hundreds. It's a classic example of inequality reinforcing itself through educational opportunity.

One of the problems, admittedly, is that, as noted, this is anecdotal. And most of the other evidence that inequality thwarts opportunity is too, showing that, for example, the inequality of enrichment expenditures on kids or college completion rates grew as income inequality grew. It's evidence but it's circumstantial.

But it's convincing to me, and to most others who've looked at this closely, so I don't for a second buy the argument that inequality is economically benign.

More challenging was their point that income concentration is a lot more politically benign then I've been thinking. As I argue in this deck (slides 16-18), hopefully well known to OTEers, while money in politics has long been a problem, it's gotten a lot worse as there is so much more income at the top and so much more leeway for that income to "buy" the politics it wants. Read Hacker and Pierson's book, and you find it awfully hard to avoid the conclusion that we're stuck in a nasty feedback loop, where the increased concentration of money in politics locks and blocks--it's locks in policies that perpetuate its growth, and blocks policies that would ameliorate it.

An egregious example of late is that one person-Sheldon Adelson, whose net worth according to Forbes in $25 billion (yes, that's with a 'b')-by dint of the Citizen's United decision, was able to keep a candidate in a national primary for months on end. That strikes me as profoundly undemocratic, and is a potent symbol of how corrupt our political system has become.

But Reihan and Scott argued that perhaps this was less portentous than all that. It was basically just a rich guy wasting some money, indulging a fantasy or something (hey, whatever turns you on, I guess). As Scott put it, if Gingrich wins the election, I'll have a point. And of course he won't.

That's interesting, although it's a bit weird to contemplate that allegedly smart investors would make such foolish investment. But are they really that foolish? They're using their unimaginable riches to steer the ideology, and they're doing it throughout the system, from local school boards to national elections. This is scary and damaging to America.

I'm open to good arguments from smart people like Scott and Reihan. But I simply don't see how these extreme economic, social, and political imbalances are so benign. I fear they're cancerous, and if we allow ourselves to be distracted by adjustments to deflators or we over-discount correlations because we haven't yet determined causality, that cancer will metastasize and America will be in real trouble.

Added bonus/penalty: here's Scott and me debating this stuff on the radio yesterday.