I was listening to an interview with Tim Geithner this weekend, and after going through his (highly readable) new book, they asked him where he thought the economy was headed. "I don't believe forecasts," he said, which sounded smart to me (he then proceeded to forecast).

He was pretty bullish about growth, generally arguing what I would say is the current conventional wisdom:

-the deleveraging cycle by households and businesses is over;

-despite a few indicators to the contrary, the housing market is gaining strength;

-there's stored up untapped demand in residential housing;

-Q1 GDP was an aberration;

-federal fiscal drag is much diminished;

-Europe and China have various issues but they won't shave much off of us.

I think there's virtue in all of these but I'm still less bullish, by which I mean I'm still worried that we slog along at trend, without closing output gaps nearly fast enough, if at all. I think some strong negatives are at work as well, which I'll elaborate in a moment.

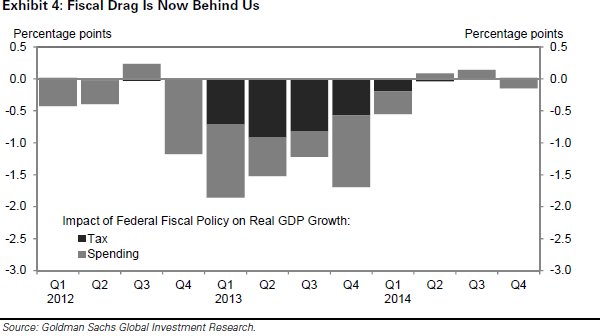

First, let's look at a few of the positive claims above, using some typically excellent slides from GS researchers. The most important, by my lights, is the absence of the fiscal headwinds that smacked the heck out of 2013. The figure below reveals the fiscal impact of taxes and spending to be largely neutral this year (part of that spending is ACA related, btw). Yes, an economically smart public policy would apply stimulative fiscal policy right now, but remember: the key variable here is "fiscal impulse," the difference in this year's fiscal position and last years. It that regard, the "do-no-harm" bars for 2014 are a big, important improvement over 2013.

Source: GS Research

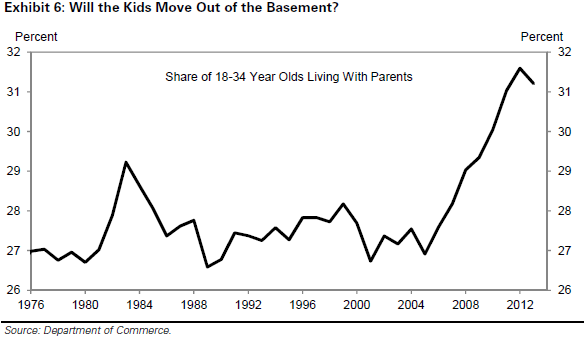

Second, a significant factor driving certain positive forecasts in recent years is pent-up demand for household formation. This next figure shows the huge spike in household-formation-aged adults bunking with the 'rents. It's at least twice its level relative to the early 80s downturn, though note the slight downturn at the end. So, optimists look at this and figure--not unreasonably--that what goes this far up must come down, leading to more activity in housing and all the downstream economic action that entails.

Source: GS Research

On the other side of the equation, however, are some negatives that shouldn't be overlooked:

-By various measures, the housing market has stumbled. Both supply (starts, sales of existing homes) and demand (price growth, mortgage applications) are down or decelerated. Moreover, the stumble looks to me to be intimately related to the pretty sudden and sharp rise in mortgage rates that occurred about a year ago, on the heels of the "taper tantrum," in tandem with the fact that credit access remains limited. There's a regional dimension to this, as some markets remain strong, but that's a hint too: those regions look to me to be the ones with more income and job growth.

-Which brings me to the next negative: weak wage and income growth for middle and low-income households. By one measure, real median household income is still down 4 percent real over the recovery, and has been flat or rising very slowly, as have wages generally, over the past few years. And a big reason for that is...

-Labor market slack: it's improving and steady payroll job gains are a plus. But the 6.3 percent print on the unemployment rate is biased down due to weak labor force participation such that there's little pressure in the job market that would enforce a more equitable distribution of earnings.

-Which raises another negative: inequality. I've written that it's hard to find convincing evidence that high and rising income inequality hurts longer-term growth through the predicted consumer demand channel (the idea that in a 70 percent consumption economy, if most of the growth goes to households with relative low spending propensities, growth should slow). But that's in no small part because the bottom 90 percent offset their stagnant incomes with leveraging and a housing-inspired wealth effect. Neither of those offsets are particularly operative right now.

-Speaking of leveraging, all the data series I know of on this show two things, but the optimists look at only one of them. They show that households are deleveraged, i.e., leverage indices are back to pre-recession levels or below. But they don't show, at least as far as I've seen, any inflection point implying that the deleveraging cycle is over. Absent that, I'd be cautious reading too much into the first point re levels.

-Finally, "hysteresis," the phenomenon of cyclical weakness morphing into structural weakness. I've got a very interesting piece on this coming out soon, if I may say so, and it shows the damage done to the growth rates on both our own and many other economies by the great recession and the series policy mistakes made in its wake.

Not trying to be the skunk at the garden party here. Just trying to keep it real and not lean too far over the skies as we glide over alleged green shoots that turn brown in the time it takes for a head fake (ouch!!--see what happens when you're over-caffeinated?!).

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.