A few hours before heading out to see Joshua Ferris read from his second novel, "The Unnamed," at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble in New York City, I noticed a curious trend on Twitter. The discussion abut Ferris seemed to resemble less a writer of literary fiction than that of a musician or celebrity:

"Can't wait to go see Joshua Ferris in a few hours! Is it weird that he's a rock star in my eyes?"

"Heading out to Ferris reading. I brought an extra bra to throw on the podium while he's reading."

Even New York Times bestselling author Alisa Valdes-Rodrigues got into the flow, remarking, "Has anyone read the latest from Joshua Ferris? Getting it today, mostly because he's sexy."

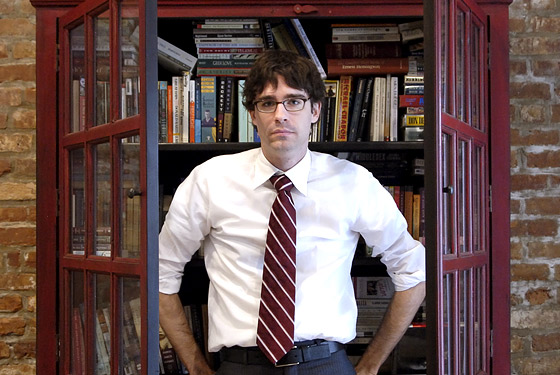

Very often in publishing, there exists either buzz surrounding a book or buzz surrounding an author. It is very infrequently that you can sense a palpable buzz around both. And perhaps just as infrequently is a writer of literary fiction described as "sexy." So how does Ferris respond to possibly being, as I not-so-subtly said on my own Twitter page, as the 'Edward Cullen of the literati'?

"I suppose the book made an impression," Ferris says modestly. "And people like labels."

Yet for someone whose second novel has been received with the kind of fanfare and review attention reserved for a sparse few writers, it has taken Ferris some time to realize that his work has touched a nerve. "I suppose I realize it only now, and that might make me sound very dense, but I've been accused of being dense before." He continues:

I never had (a readership) before. Perhaps there had been some avid kook out there waiting for my next story to appear in a literary journal but I doubt it. it was a change, but it was an abstract change. It wasn't a palpable feeling as I was writing my second book and it's not that as I write my third. I think it's a very bad idea for someone to start writing for a readership.

Unlike most debut novelists, Ferris seemed to have an eager readership awaiting his first full length work even before "Then We Came to the End" was published. Every few years, the literary establishment seems to anoint the next Next Big Thing. Zadie Smith. Jonathan Safran Foer. Benjamin Kunkel. Marisha Pessl. And in 2007, Joshua Ferris. Ferris's first novel, "Then We Came To The End," was a national bestseller, and according to his publisher, Little, Brown, it has approximately 250,000 copies in print in hardcover and paperback. It was nominated for the National Book Award, won the PEN/Hemingway, was named one of the New York Times "Top Ten Books of 2007," won the Barnes & Noble Discover Award, and appeared on the cover of the New York Times Book Review.

These are all accolades that most writers will fall short of achieving over the course of an entire career. Ferris, now 35, achieved them all with his first book. And a few weeks ago he released his second novel, "The Unnamed," about a man afflicted with an unknown illness which compels him to walk (and in the process wreaks havoc on his health family and sanity) which had the daunting task of following up one of the most successful literary debuts in years. So how does a writer follow up a book that was a runaway critical and commercial success? What are the challenges he and his publisher face? And did the literary establishment seemingly go out of its way sharpen its knives to try and cut Ferris down to size?

"Of course there's pressure to publish ("The Unnamed") well," says Ferris's editor at Little, Brown, Reagan Arthur. "But it's the best kind of publishing problem you could have."

"('The Unnamed') was easier to write insofar as that I had a little bit more money than I had before. I was living on credit card debt so practically speaking it was easier," Ferris says.

I wasn't expecting to get an agent, so everything from the moment I got an agent interested in a publisher to buy it has been surprising and delightful. It had been just a singular experience and everything, including the people that entered my life because the book was bought and published and read, have become like family to me to some extent. I didn't just gain an external career that came as an addendum to my private life as a writer but I also gained a great group of friends. I'm enormously grateful for everything. There isn't anything I've taken for granted or assumed would happen.

When Ferris speaks, he does not come across as a rock star, an object of literary affection, or someone who has grown a large head from his success. He speaks in a low, even shy voice. In the audience at his Upper West Side reading are his wife and infant son. The post-reading Q&A sounds more like a respectful book club than a mosh pit. The audience members ask about motifs, motivations, character analysis, and whether the unnamed illness that drives the story is meant to be taken literally or as a metaphor.

Arthur recognizes that following a book like "Then We Came to the End" presents problems as well as opportunities.

(It's a) blessing to have done something that so many people noticed and admired, a curse to be in a position where the natural human impulse for many onlookers is to roll their eyes and wait for his comeuppance. Since he is truly one of the nicest and most level-headed people on the planet, he seems unaffected by both sides of the equation.

Despite wonderful early reviews, including starred notices from Publishers Weekly, Booklist and Kirkus, some of the critical reviews for "The Unnamed" have been as unkind to Ferris as the unnamed disease is to his protagonist Tim Farnsworth. Major outlets such as the Washington Post, USA TODAY and the New York Times offered extremely negative assessments. (If I can add my two cents, I found "The Unnamed" beautifully written and often wrenching.)

Yet as Ferris states bluntly, "Some of the bad reviews have been perplexing in their lack of sophistication."

Ferris continues:

I think that there have been displays of an impoverished reading of the book. I get the distinct feeling at times that certain critics have not risen above a 10th grade level of reading and that they approached the book with expectations of preconceived notions that then drive a very boneheaded reading. In other words they don't allow the book's rules to establish themselves before applying their own aesthetic criteria to it which I think is a mistake. I think a careful and adult reader allows the book to establish its world and then evaluates it on how well it does so. I also think a smart critic does not drag behind him or her like a dead horse whatever presuppositions the first book might have indicated where the second book might be about or what kind of freedom the writer might be exploring as a writer. All of those things I find unfortunate when I read a review that seems misbegotten. But I'm not sure that this is not a new phenomenon and it would be a Sisyphean task to argue against a misreading because those misreadings are an inherent part of the critical apparatus.

In the New York Times, author Jay McInerney offered several curious observations, even criticizing the notion that Ferris seems unconcerned with mining the same debauched territory McInerney did in novels like "Bright Lights, Big City."

With his second novel Ferris makes it clear that he has absolutely no intention, for the moment at least, of repeating himself or creating an authorial brand...Perhaps we should be grateful that this isn't another narrative of addiction, with all the tawdry scenes of gutter plumbing, sexual misconduct and the destruction of property. Although come to think of it, squalor and degradation can be, well, vivid.

"The McInernery review is interesting," Ferris says, "It seems to be misguided on several levels. I think (branding) is something that my publisher should be worried about, not me. My first job is to write a book that I believe is compelling and deserves the long sustained attention that any novel requires and to worry about the commerce only late in the game."

Arthur appears to second Ferris's opinion. "I think a real writer has to write the book he wants to write, without worrying about marketplace or audience -- that's the publisher's job. Writers don't live up on a cloud of ideas and artistry, of course, and I know they think about the nuts and bolts of their careers, but I think if they write with only that in mind the results would be disappointing for all concerned."

Adds Ferris's publicist at Little, Brown, Marlena Bittner:

I think he's being judged against the successes of "Then We Came To The End" to a degree, but that's a high class problem to have. And one that anyone with a well-received body of work has to deal with. There may have been an expectation that he was going to do the same thing that he did the first time out since that worked so well, but I hope that people are judging The Unnamed on its own merit....There's been a huge amount of coverage and I've been delighted with that -- with shrinking book coverage, for anyone to get more than a handful of reviews is nothing short of miraculous. Whether or not I agree with everyone's take, it's getting a lot of ink.

And when Ferris discusses what it feels like to have both a readership and receive positive reactions to his books, he sounds refreshingly like the vast majority of authors:

As the writer of the book it's hard to understand in an objective manner what it's like to have a sudden readership. Signs of that become manifest over time, and you're not really sure it's going to last. Every time you hear someone read your book and liked your book you're never sure whether that's going to follow with a similar remark from someone else. Perhaps I have low expectations, but whenever I hear someone say I liked your book I don't know if it's going to happen again.

JASON PINTER is the bestselling author of five thriller novels (the most recent of which are The Fury and The Darkness), which have been nominated for numerous awards and optioned to be a major motion picture. His first novel for young readers, Zeke Bartholomew: Superspy!, will be released in the summer of 2011. Visit him at http//:www.jasonpinter.com.