Imagine you are on foot and being chased by thousands of soldiers on horseback across a desert. All you have to do to survive is stay ahead of the horses by outrunning them each day. Sounds impossible, right? But that is exactly what the Apache warriors did for decades, to maintain their freedom and their way of life.

One of the darkest chapters in our nation's history ended nearly 100 years ago, but this year will be the first time many people hear about it. After all, there is no national holiday or three-day weekend to celebrate this anniversary. There is no opportunity for commercialism. So naturally, there has been no memorable media attention given to the event that occurred in April 1913. Until now, that is.

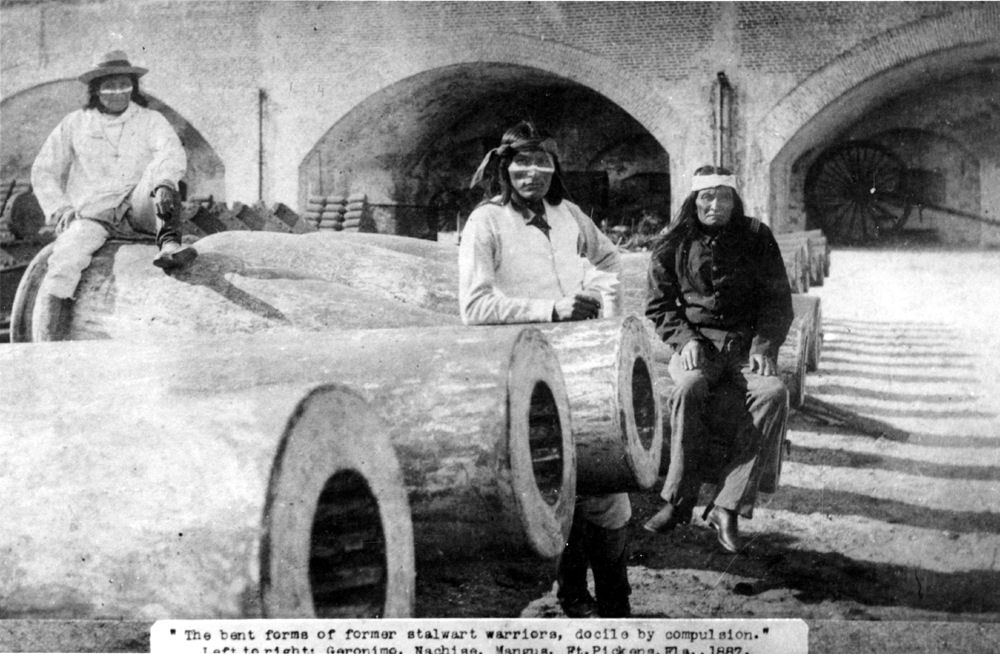

Geronimo, Naiche and Mangus as prisoners of war at Fort Pickens, Florida, 1886-1888

Geronimo, Naiche and Mangus as prisoners of war at Fort Pickens, Florida, 1886-1888

This date, like the people it represents, was meant to be forgotten as an unwelcome reminder of a distant past. After all, history is written by the conquerors; but to the Apache people, it is a symbolic date: a moment in time when they were liberated from captivity. Twenty-seven years of captivity, to be exact -- that is how long the Chiricahua Apache people were held in American prison camps. It seems that it's easier, as with other unpleasant episodes in our nation's past, for us to not remember.

Whatever the reasons are, the story of the Chiricahua Apache people -- from their own perspective -- has remained mostly untold to the American mainstream public. It is this fascinating story of spiritual fortitude, physical endurance and pure ingenuity, that inspires the inaugural Apache Freedom Run and Centennial Celebration to be held April 5 through the 6 of this year (2013).

Up until the mid to late 1800s, most of the American Indian Nations that fought the United States military were defeated; and those who did survive eventually surrendered in order to save their remaining people... except for the Chiricahua Apache, who had never surrendered or been captured. They were the last band of Indians who were free to roam as the nomadic hunting and raiding culture that they had always been, as opposed to a farming society based on the concept of land ownership and staying in one place, which was preferred by the European settlers.

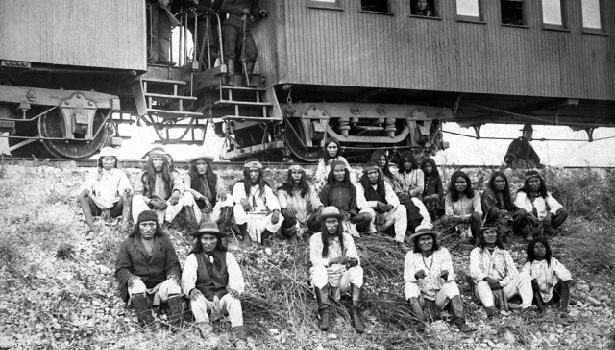

Chiricahua Apache prisoners at a rest stop along the Southern Pacific Railroad, en route to Fort Marion, Florida; September 10, 1886

Chiricahua Apache prisoners at a rest stop along the Southern Pacific Railroad, en route to Fort Marion, Florida; September 10, 1886

In the late 1800s, a decades-long series of armed conflicts (known as the Apache Wars) culminated in an intense official military manhunt to capture this last band of free Apaches and their leader, Geronimo. Sensational press coverage of Geronimo's successful evasion of United States Army fed the heavy political pressure behind the Apache Campaign of 1886 (also known as the Geronimo Campaign). The Apache were notorious for defying the United States government; and Geronimo, along with his band of 39 warriors had become the symbol of resistance. They had to be stopped, captured or killed at any cost.

At the height of the chase, over 9,000 men on horseback -- including 5,000 cavalry, 3,000 Mexican soldiers and 1,000 civilian vigilantes -- pursued Geronimo and his men. The Apache warriors knew that the cavalry horses had to be rested and watered every 40 miles in the desert. So Geronimo and his men would cover over 60 miles each day, in order to always be ahead of the soldiers.

This was natural to them, because to the Apache, running is a sign of a warrior-ship. Apache children learned to run while holding a mouth full of water in order to promote deep, rhythmic, lung breathing. This kept their throats from drying out, which would happen if one panted in the dry desert air. These runners where known as Spirit Runners.

They would enter into a trance-like state as they would cover many miles, keeping up a steady pace of six minutes per mile, without any sign of fatigue. In this way, against all odds, the Apache avoided capture for decades.

Finally, in September 1886 at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, Geronimo and his warriors surrendered. By then, other Apache bands had already been persuaded to go willingly into internment. After Geronimo's capture, the remaining free Chiricahua people were sent by train (with no toilets and often with windows nailed shut) to prison camps in Florida and eventually, to Fort Sill in Oklahoma, in 1894. A large proportion of those imprisoned were women, children and other non-combatants. They were held as prisoners of war for 27 years, longer than any other people held by the U. S. government on U.S. soil. Right: Jay ran the 2013 Los Angeles Marathon to help publicize the Centennial Apache Freedom Run.

When the first group of Apache were finally released from Fort Sill in April 1913, only a few hundred out of the thousands originally imprisoned had survived. To add insult to injury, they faced the incredible injustice of not being recognized by the U.S. government as an Indian Nation. This meant that they had no "reservation" land assigned to them. They literally had no place to which they could return. "Freedom" was not a joy; it was yet another forced displacement.

It was the Mescalero Apache (who lived alongside the Lipan Apache, high up in the New Mexico green mountains covered in tall pine trees.) that invited the Chiricahua to live with them on their lands near Alamogordo, New Mexico. Out of the 250 people who were released from Fort Sill, 183 joined the Mescalero Apache on their lands. The other 77 remained on small farms near Fort Sill.

On April 4th of this year, it will have been 100 years since the Chiricahua Apache left Fort Sill, Oklahoma. This year, the inaugural Apache Freedom Run will mark the date in a significant way that we can all appreciate. To remember the Apache warriors who ran for decades in the Southwest desert, Apache runners will run 501 miles, in stages, starting in Fort Sill, Oklahoma on April 2, and arriving at the Mescalero Apache reservation in New Mexico on April 5. I am extremely honored to have been invited to run one of the final legs of this historic event.

On April 4th of this year, it will have been 100 years since the Chiricahua Apache left Fort Sill, Oklahoma. This year, the inaugural Apache Freedom Run will mark the date in a significant way that we can all appreciate. To remember the Apache warriors who ran for decades in the Southwest desert, Apache runners will run 501 miles, in stages, starting in Fort Sill, Oklahoma on April 2, and arriving at the Mescalero Apache reservation in New Mexico on April 5. I am extremely honored to have been invited to run one of the final legs of this historic event.

At the end of the run at the Mescalero Apache reservation, participants, family and guests will celebrate with a parade, a feast in the mountains, traditional War dances as well as a re-enactment of the wagon train arrival of the freed Fort Sill prisoners of war in Tularosa, New Mexico.

This celebration reminds me that the Apache spirit is alive and thriving high up in the sacred white mountains of the Sierra Blanca in New Mexico. But this is not just a celebration for the Apache people, it's a remembrance and a chance to honor the amazing blood lines that run through each of them -- a reminder of the unbreakable will of a people who survived decades of pursuit, extermination of their families and deprivation of basic human necessities. They leaned on each other, on their spiritual beliefs and on their centuries-old tradition of perseverance.

One can't help but be inspired by the unbreakable spirit of a people who survived the harshest ordeals by always keeping their spirits alive, and there is some strong medicine among the Apache people, good medicine that we can all learn and be inspired by. This historic event is open to everyone from all four directions to come celebrate the Apache Spirit.