© Stalker Production, used with permission.

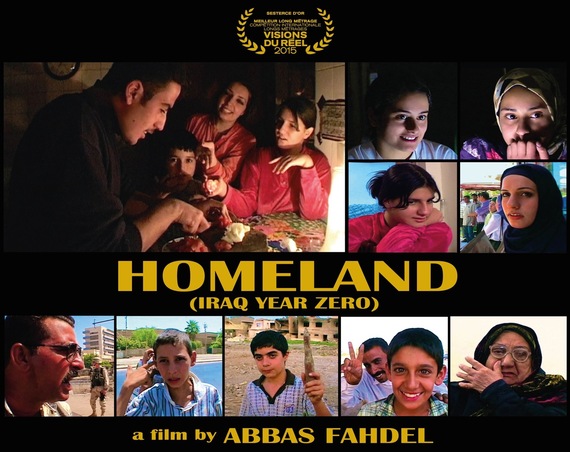

Abbas Fahdel's Homeland (Iraq Year Zero) is the most significant work of art to come out of the Iraq war.

The documentary follows months, weeks, and days leading up to the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq and months into the subsequent occupation. Shot in Baghdad and the countryside on a lightweight video camera, this electrifying five-and-a-half hour film divides into two parts, Before the Fall and After the Battle.

The world premiere of Homeland took place at the 2015 Swiss film festival Visions du Réel, where it was awarded best feature in the international competition. On Oct. 5, the movie has its North American premiere at the New York Film Festival.

Using a long-take style reminiscent of Claude Lanzmann's epic Shoah (1985) on the destruction of the European Jews, Before the Fall wanders through the day-to-day lives of the director's family and friends in Baghdad, the capital's city streets, its bazaars, and, eventually, their homes in the countryside, possible safe havens from the looming Anglo-American Blitzkrieg.

A kind of time capsule, Homeland opens in Baghdad at the home of Fahdel's brother Ibrahim. Among others, we meet the director's nephew Haidar, a precocious, vibrant 12-year-old boy, who plays an increasingly significant role as the movie unfolds. Eventually, after the fall of the capital, Haidar accompanies the filmmaker on numerous excursions throughout the city.

Watching Homeland is like pulling a photo album off the shelf, dusting it off, revisiting family and old friends, made increasingly poignant by the passage of time. In the faces of ordinary Iraqis gazing into his camera, Fahdel reasserts the beauty and magic of the close-up.

© Stalker Production, used with permission.

Retrospect hovers around the edges of the screen, as we know the terrible future that awaits Fahdel's relations. Anxious, they still go about their affairs as normally as possible. They prepare for the coming invasion, just in case, not knowing if, or when, it will come. The director's niece and her cousins chat about marriage and share their desire to eventually open a gynecological clinic. To partly paraphrase an old Yiddish saying, women plan and the U.S. government laughs.

At the end of Part 1, we learn to our shock - from an intertitle - that Haidar will die in the coming months. A chronicle of a death foretold.

In the aftermath of 9/11, the Bush administration was hijacked by a minority of neoconservatives, whose sights had long been set on invading Iraq and deposing America's one-time ally Saddam Hussein. After the Battle carefully chronicles the terrible wake they left in Iraq.

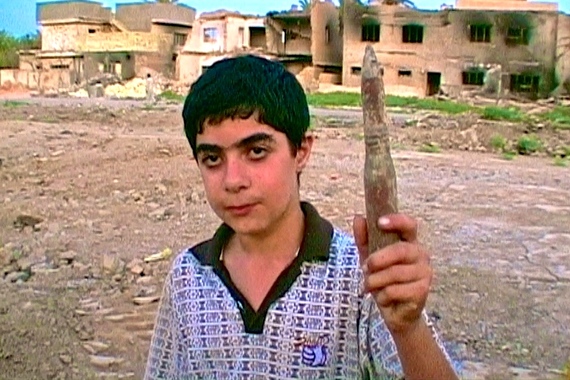

Strikingly, there is no "shock and awe" in Homeland, our "rockets' red glare" are kept entirely off-screen by the filmmaker. Fahdel refuses to recycle the spectacle of destruction that played 24/7 on American media. Instead, he records its aftermath, the traces left behind.

Iraqi boy with leftover shell from American assault on Baghdad. © Stalker Production, used with permission.

Unlike Claude Lanzmann, Fahdel does not appear on camera and his off-screen presence is less angry, more contemplative. By discussing Fahdel's masterpiece in light of Lanzmann's own, I am not equating the extermination of the European Jews with the obliteration of Baghdad and Iraq. Only time will tell where the destruction of this Middle Eastern country ranks in the long list of world atrocities.

In After the Fall, ominous portents emerge in the early weeks and months of the U.S. occupation. Looters thrive, the occupiers stand by, chaos reigns. Fahdel's protagonists draw unsettling equations between the old and the new, "Saddam and the Americans brought us nothing but misfortune." In the street, one Iraqi says, "Their soldiers didn't come to free us. They came to enslave us and to exploit our country's resources."

Like Shoah, Homeland is a great work of history. Inspired by a Paul Klee painting Angelus Novus, German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin described his vision of the angel of history:

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward.

Filming virtually by himself, Abbas Fahdel is just this kind of witness. Director. Producer. Cinematographer. Editor. Angel of history.

Traumatized by the death of his nephew, Fahdel stopped videotaping. An Iraqi exile living and working in France, the director mourned for more than a decade, only completing Homeland twelve years later.

To those of us who live far from Baghdad, Fahdel has written an indelible scroll of the Iraqi capital, once upon a time. Homeland remains an everlasting tablet of a proud people preparing, and enduring, a destiny written by a handful of extremists in Washington, DC, itself once the capital of a lawful country.

From many a bombed building, Fahdel makes silent stones speak. Through its duration and attention to everyday detail, Homeland allows us, symbolically, to sit shiva with the extended Fahdel family, friends, and, by implication, the Iraqi people, as they mourn their dead. Paying such a home visit is a deed of kindness and compassion.

© Stalker Production, used with permission.

Homeland certainly does not soft peddle Saddam Hussein's brutality. Fahdel's brother points out the country's largest mass grave, containing victims of the 1991 post-Gulf War uprising. Firing guns into the sky, Iraqi citizens celebrate the deaths of Hussein's cruel sons. Fahdel's network of relatives and friends includes opponents of the regime imprisoned, tortured, and/or murdered in the 1980s and 1990s. We mourn them, too, as we grieve the victims of the American occupation.

Despite the escalating chaos, there are small signs of hope. Fahdel's niece passes her university exams. In the penultimate sequence, a relative gives birth, to the great joy of the extended family. "She looks like her grandmother!," one exclaims. In the final scene, however, as they drive home from the hospital, unknown gunmen strafe their car, killing Fahdel's 12-year-old nephew. "Uncle!," he cries, the last word spoken in the film.

My daughter's high school civitas homework notes that Iraq was part of the Fertile Crescent, the cradle of civilization, where language, agriculture, trade, and science originated. Now, thanks to the Bush regime, there is literally no place like home for millions of Iraqis, in the shards of their country or on the trails of exile. The crooked shall not be made straight.

The epic Homeland (Iraq Year Zero) breathes life back into the vibrant society of Baghdad in 2003. Like Shoah, it is a monument to the power of cinema to recreate a vanished world. Every second in its company is richly-spent. When you have the chance, invite Abbas Fahdel into your home; "Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares."