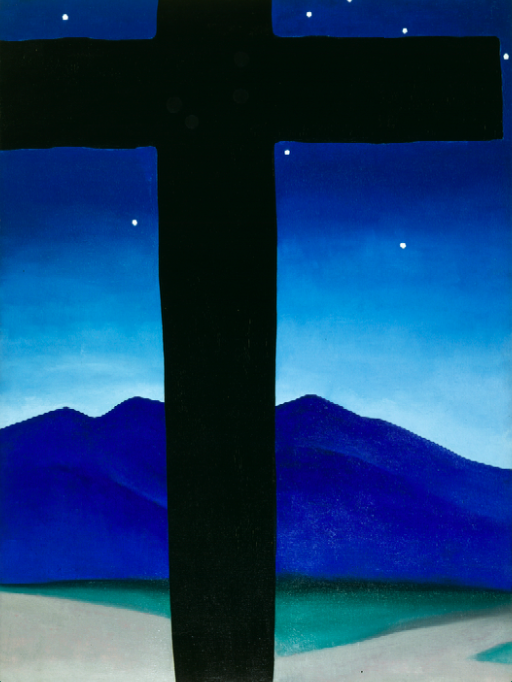

Black Cross with Stars and Blue, 1929

Oil on canvas

40 x 30 in. (101.6 x 76.2 cm.)

Private Collection

© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

It began with the opening of an exhibit of the works of Georgia O'Keeffe. But it quickly became a pilgrimage to discover the woman behind the work. The show "Georgia O'Keeffe in New Mexico: Architecture, Katsinam, and the Land" officially opens May 17, 2013 at the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. But I flew in early for a preview.

Serendipitously, I was in Taos just the week before and so my journey began before I even knew it was underway. As we drove into town I gasped as I saw San Francisco De Asis Church fly past my window. We made a u-turn so I could get a closer look. I recognized the Church from O'Keeffe's paintings. I felt a strange intimacy despite never having seen it in person before.

I visited O'Keeffe's old haunts, the Mabel Dodge Luhan House where O'Keeffe spent a short time -- not long as the two strong female presences were more than any four walls could hold -- and the Sagebrush Inn, where O'Keeffe lived and painted the hotel's only third floor room.

But this story actually begins more than 25 years ago. I don't know how I stumbled upon O'Keeffe. But I quickly became obsessed, even imaging myself as her apprentice one day, cleaning her brushes and carrying her paints. But she passed away in 1986.

Though my artistic skills are beyond lacking, I painted a portrait of her in a high school art class, her mountains and vast, blue sky my backdrop. By some miracle, it turned out to be a beautiful piece. In fact, my art teacher was so impressed that he accused me of getting another student to paint it for me. How could I have possibly painted it, he wondered.

But when he was satisfied that no one living had helped me, he decided it was the spirit of O'Keeffe herself who had painted it through my hands. Impossible, I know. But I have cherished the idea that it might be true all these years later. And I have long dreamed of knowing her better as an artist and of one day knowing her New Mexico, her land, her "faraway," as she fondly called it.

I had been to the O'Keeffe Museum before. But this new exhibit is something truly remarkable. The show is titled "Georgia O'Keeffe in New Mexico: Architecture, Katsinam, and the Land" and was organized by the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe.

It opened at the Montclair Art Museum September 28, 2012 and later moved to the

Denver Art Museum on February 10, 2013. On Friday, May 17, 2013, the show will open at the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, where it will remain until September 8, 2013 at which time it will travel to the Heard Museum Phoenix, opening Sept 27, 2013.

The show is O'Keeffe's New Mexico, the churches and crosses and landscapes and folk art, all created between 1929 and 1953.

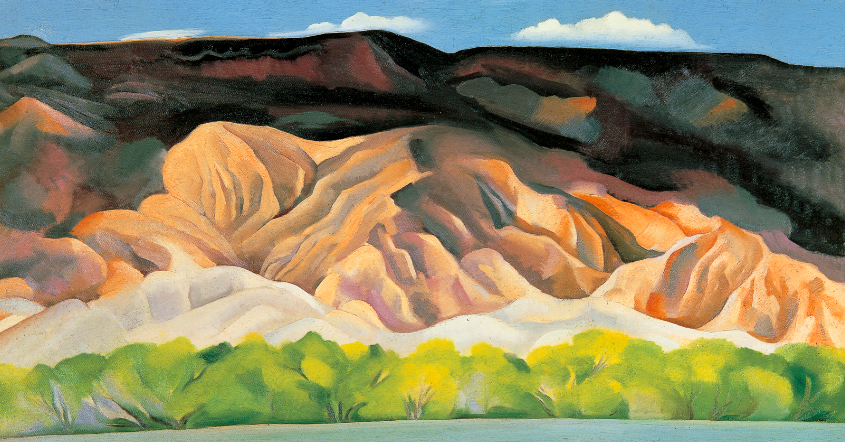

The paintings are juicy, pulsing with color. The mountains are personal. They are hers. They are like layers of blankets, piles of earth set forth to glow in rich, earthy tones, set in sharp contrast against the bluest of skies. They look as if they might rise up and embrace you in their folds.

The show is an insight into the first years O'Keeffe spent in New Mexico. "There was nothing that came before her eyes that didn't interest her. She begins from the visual world and ends up with an abstract painting," explains curator Carolyn Kastner.

It happened before I expected it to. Although I admit I expected it. The minute I saw Black Lines, a watercolor O'Keeffe painted in 1916, the tears came. As I walk through the galleries, I wonder, "How could she do this? How could she be so close, so intense so true, and yet so abstract?"

The swelling movement of At the Rodeo, circling and pulsing in brilliant colors. The rich burgundies and greens of Rust Red Hills, like velvet or fur. As I walked from gallery to gallery, my breath would catch. This time, this woman, these places. It's revolutionary, revelatory, miraculous.

The brilliant blues of Pelvis IV 1944 and Hill, New Mexico 1935. The mountains like beasts with teeth, like pillows, all softness and plush in Black Place II 1945. You want to reach in and rest inside. O'Keeffe constantly and effortlessly moved back and forth between abstraction and representation. She was a modernist in the truest sense.

One piece in the show, Black Cross with Stars and Blue 1929, is on loan from a private collection and is only showing at the O'Keeffe Museum. It is literally the only opportunity one might ever have to stand before its lines and colors, the extraordinary way in which the landscape comes creeping despite the cross being the painting's focus.

The next to the last gallery is a magic, little space filled with O'Keeffe's Katsina Tithu or kachina dolls that depict Hopi spirit beings, looking out at you from all around. You might swear they are watching you and you quickly understand O'Keeffe's own fascination with them. In the final gallery, two large textiles from Ramona Sakiestewa and a painting from Dan Namingha hang, works on display to contextualize the show.

O'Keeffe abstracted the miracles of New Mexico's landscape, and, through her hands transformed them into images that simply cannot be ignored. She wanted us, all of us, to really look at the things, at the pieces of the natural world that so enthralled her, to see them as she saw them. So she abstracted them, enlarged them, enlivened and invigorated them.

"Still -- in a way -- nobody sees a flower -- really -- it is so small -- we haven't time -- and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. So I said to myself -- I'll paint what I see -- what the flower is to me but I'll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it," O'Keeffe once wrote.

After seeing the show, my appetite was more whet than satiated. So, I stopped in at the Research Center that is a part of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum "campus," where collections of O'Keeffe's paints and pastels and paint chips, as well as the shells and rocks and bones that O'Keeffe loved, fill long, deep drawers where they live under glass in tiny rows.

It is an examination, an exploration into O'Keeffe's process, a study in how she observed and carefully considered color and the natural world and abstracted what she saw into a focused vision of that which she wanted her viewer to see. "She was incredibly thoughtful," explains Eumie Imm Stroukoff, Emily Fisher Landau Director of the Research Center, "Mapping out colors, not just in the moment. This constellation of assets, paintings and photos and materials and sketches gives you a broader understanding of O'Keeffe as an artist and a thinker."

Seeing O'Keeffe's sketches and paint chips, you can envision her sketching and composing. Seeing the tiny rocks and bones she collected, you come to understand that she did with them what she does with flowers, enlarging them, making it impossible not to look, not to see.

"Georgia O'Keeffe was an abstract artist. She looked at nature and then abstracted what she wanted to be seen," Stroukoff explains

To have walked in her steps in Taos and then stood before the paintings was nothing short of thrilling. To see the show and explore the Research Center was inspiring. Still, I wanted, I needed more, so I set out for Abiquiu , where O'Keeffe's long time companion, Agapita Judy Lopez, who is now the Director of Abiquiu Historic Properties and the Rights and Reproductions Manager (affectionately referred to as Pita) was waiting to show me O'Keeffe's home.

When I arrived she had a surprise for me. She invited me to be the very first non-employee, non-family member to see O'Keeffe's bomb shelter. O'Keeffe had a shelter, Pita explained, not because she was so concerned about saving her life but because she was incredibly curious to see what would become of the landscape she so loved should a disaster occur.

It is, as one might expect, a small cinderblock room with a lead lined door. Inside there is water, a Geiger counter, metal framed bunk beds, and little else. It was surreal to be in there, to be the first to see it. It was an incredibly intimate experience that I will treasure.

Pita is the third generation of her family to work for O'Keeffe, and she is dedicated to keeping the property precisely as Miss O'Keeffe, as Pita calls her, would want it. Everything is just as O'Keeffe left it, sparse, monastic, centered on the landscape, stunningly beautiful in its simplicity.

There is only one painting of O'Keeffe's hanging in the home because O'Keeffe believed that if they were in view all the time one would stop seeing them. Outside of the house, the garden space is vast. At one time it contained nearly all of the foods O'Keeffe ate and all of the flowers she painted.

No photos are allowed on the tour and no notes may be taken either, not even if you're a writer. It was challenging, but also kind of wonderful. I had no choice but to be fully present as I stood in O'Keeffe's own bedroom, where visitors are, as a rule, not allowed. I also stood in her salita where O'Keeffe would prepare her canvases.

Most notable is what is not in the house. No clutter. No piles. No "things" really. What you will find inside are the rocks she so loved, a stereo, books, jars for canning, a yogurt maker, a linen press, a few of her own sculptures, as well as one made by Juan Hamilton. The furnishings, the décor, it is all miraculously simple, nothing to impede the sweeping views.

I wandered the grounds and felt nearly overcome imagining O'Keeffe painting the same landscape by which I was surrounded and embraced. I felt humbled and honored to be in the presence of her land, her mountain, her skies and trees. To me they have been and always will be hers because it was she who gave them to me in every painting and drawing and sketch I had studied.

Before heading back to Santa Fe, I decided to stay the night and soak in the natural springs of Ojo Caliente. I wanted to commune with all of the natural elements that O'Keeffe so loved. There's no record of O'Keeffe having ever been there. But it's hard to imagine she wouldn't have been charmed by the medicinal waters nestled in the mountains that she claimed as her own.

As I soaked in the warmth under a sliver of a crescent moon, pinion wood crackling in the kiva fireplace, sparks flying up in the night sky, the great mountains lit bright against the darkness, luminarias lining the pool, it suddenly all clicked. To truly know O'Keeffe, one must fall deeply in love with New Mexico and her awe-inspiring vistas, with which she had a lifelong love affair. I grabbed my robe and raced barefoot to my room and my waiting computer.

I lit a fire in the fireplace and my fingers raced across the keys. It may have taken me many years, but I finally did it. I found her. I found Georgia O'Keeffe.

Back of Marie's No. 4, 1931

Oil on canvas

16 x 30 in. (40.6 x 76.2 cm.)

Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

Gift of The Burnett Foundation

© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

Kachina, 1934

Oil on canvas

22 x 12 in. (55.9 x 30.5 cm.)

Private Collection

© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

Ranchos Church No. I, 1929

Oil on canvas

18 ¾ x 24 in. (47.6 x 61 cm.)

Collection of the Norton Museum of Art,

West Palm Beach, Florida, Purchase

the R.H. Norton Trust

© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

Chama River, Ghost Ranch, 1937

Oil on canvas

30 ¼ x 16 in. (75.8 x 40.6 cm.)

New Mexico Museum of Art

Gift of the Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe, 1987

© New Mexico Museum of Art