A few months ago, we started debating the strategy of the increasing cross-over of Institutional Investors (mutual and hedge funds) into Venture Capital territory. Folks like T. Rowe Price and Tiger have been showing up a lot in later stage rounds of venture-backed companies, and many on Sand Hill have questions and comments about their motivation, behavior, and general wisdom (or lack thereof). Some have gone as far as linking this "bubble" to the bubble of 2000.

We had different perspectives, one from Silicon Valley, the other from Wall Street, so we turned to the data on the past two years' IPOs and prior private rounds for answers. We analyzed the spread between private and public pricing and found something that surprised us both. Not only were the Institutional Investors not getting it wrong, they were making a lot of money getting it right. You wouldn't know that from the headlines we're seeing with ever-increasing frequency.

So where's the disconnect?

1. Investor Return Expectations

According to Morningstar, mutual fund investors experience (annualized) 5 - 12 percent returns. VC investors shoot for a 300 percent - 1000 percent total returns. That's quite a gap.

Mutual funds are showing up predominantly in what are termed "pre-IPO" rounds, implying an IPO is imminent and an exit and public company status is almost guaranteed. This is very different than most traditional VC investments. The return profile (with some exceptions) isn't guaranteed, but investors can be confident an exit is likely.

For mutual funds, this becomes an exercise of entry price arbitrage.

If an institutional investor wants to own stock in a company at IPO, and they think they can buy cheaper stock in a private round, why not participate in the private round?

VCs have a different investment objective in the same round, and the return profile is worlds apart. Early stage VCs may simply be protecting their ownership stake by taking their pro-rata, while late-stage VCs new to the company may look for 3x+ from their investment. A crossover investor needs only a slight premium to their normal returns.

2. Investor Returns

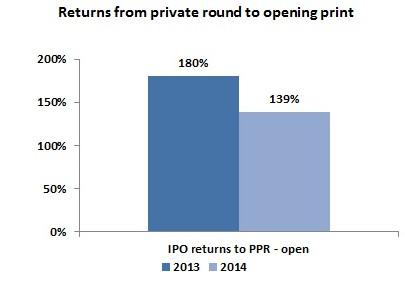

We looked at returns from the last private round to the opening trade of IPOs. Measuring returns based on the opening trade is important because it represents the investors' first public option to purchase stock if they pass on a private round, and, outside of any stock they are allocated on the IPO, they will be buying on the open market like everyone else.

Investor returns, from the prior private round to IPO opening print, were 139 percent in 2014 (they were 180 percent in 2013).

So our data shows that investing in late-stage private rounds is actually wildly profitable. All this with companies in our data set going public an average of 20 months after their last private round.

Based on these returns, there's no reason to expect meaningful change in Institutional Investors jumping into Venture-backed companies, or pricing late-stage rounds, until the returns have been squeezed out of the system. Late-stage VC's however must pay less to achieve their target multiples, and will continue to be priced out of later rounds.

3. Private Company Size

The Wall Street Journal created their "Billion Dollar Start Up Club," of 83 unicorns with valuations over $1B, illustrating that for the first time there are a significant number of private companies large enough to attract Institutional Investors initial investment without an IPO event.

Warnings of private company valuation inflation generally focus on the high notional price tags of private round valuations. The warnings are that valuations are lofty and that these companies should already be public.

This trend is a function of technology allowing companies to scale faster. The last few years brought smartphone and social media proliferation, the ability to manage big data and much more. Uber, at $41B, or SnapChat at $15B couldn't exist five years ago, let alone grow at the pace they're growing.

Lyft was started in 2012, slightly over two years ago. They are a great company, growing topline revenue at a 5x, but are not yet profitable. They do have profitable markets however, and according to Tech Crunch should do $1B+ in revenue in 2015. They are both not ready to IPO and very fairly valued at $2.5B, especially with at least $530mm in cash from their recent raise.

In many cases these $1B+ companies are only a few years old, but regardless of their public or private status, they have real revenues and viable, dynamic business models.

Just because a company is doing $1b in revenue doesn't mean it's ready to IPO. If a company is still in high growth mode the scrutiny of numbers and focus on profitability can be debilitating.

4. The Risk vs. Reward

The risk is rarely that these pre-IPO, high revenue, high-value companies fail; the risk is in the returns. We know from our earlier data analysis that returns are declining, but on average they're still astronomical.

Lets look at the two last tech IPOs to understand the risk and reward to late stage investors; Etsy and Apigee. Etsy was a clear winner, outperforming the average returns from 2014 vintage IPOs, while Apigee was a feared down round IPO, pricing at a 23 percent discount to its last private round.

Etsy's last private round priced at $10.60 in April, 2014. The IPO priced at $16, with an opening print of $31. Last round investors realized an 190 percent return at opening print

Apigee priced its last private round in May, 2014 at $22.16 and priced the IPO stock at $17 with an opening print of $20.00. Last round investors realized a -10 percent return at opening print. While the stock priced at $17 (a -23 percent return), it opened at $20 creating a -10 percent return.

A negative 10 percent return, which is actually -6 percent with the anti dilution clause, is nothing scary - especially as part of the overall average of a 139 percent return. No one likes to lose money, but we don't think it's time to pull the fire alarm. These are big boy investors making educated investment decisions, and generating real results.

What to make of it

The landscape is changing, yes -- crossover funds are increasing the bid and inflating multiples for late stage companies, yes -- and in effect they are out bidding traditional VCs.

VCs continue to passionately warn about the dangers of this inflation, but the data shows that the perpetrators of the inflation are seeing spectacular returns.

Not surprising that you haven't heard any of the mutual funds complaining.

Sounds a little like the Seniors crashed the Freshmen private party and took a lot of their girls... we'd be pissed too.