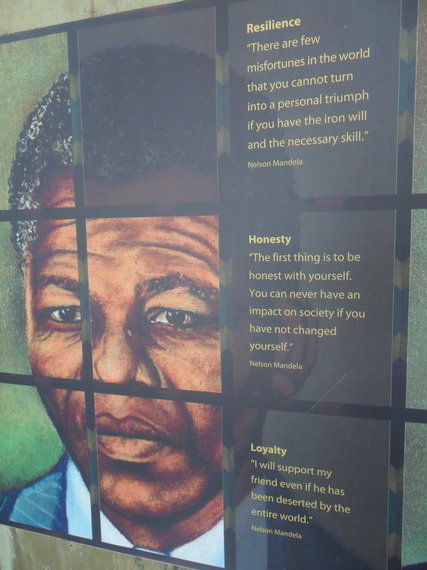

I'd been on South African soil for only two days, and already I could feel the stirring of a profound evolution deep inside my soul. It was percolating, bubbling under, almost certain to eventually erupt in a big bang of mental and emotional transformation.

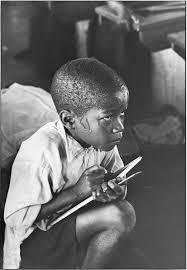

It started at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, in front of an exhibit dedicated to House of Bondage, Ernest Cole's book of photo essays documenting the social, economic and political injustices of South African apartheid that was published in 1967 and promptly banned in the country. I was transfixed by images I'd never seen that still looked strangely familiar. As I stood there with tears welling up in my eyes, I felt an unsettling sense of déjà vu. Actually, I had seen those images before, not in the same pictures, but in ones just like them.

I'd been bombarded with the images all my life -- in stories I'd been told, in chapters of history books I'd read, on pages I'd pored over in encyclopedias, in movies I'd sat through uncomfortably. The travesties of the Civil Rights era on one side of the world were committed concurrently with the travesties of apartheid on the other, as depicted in Cole's provocative and evocative photos.

Among the excerpts (photos by Cole, words by Thomas Flaherty) hanging on the wall was a stunning sentence, one simple declaration that I read over and over, until it threatened to sink my spirit and break my heart under the weight of my soul's sorrow:

"It's an extraordinary experience to live as though life were a punishment for being black."

Suddenly, I felt connected to South Africa, to Africa, in a way I had always been told I was supposed to, because I'm black, because it's where my ancestors originated. As I looked at one particular image, a black and white photo of a little school boy melting in the sweltering heat of the classroom and struggling to concentrate, I saw myself. I never had to learn under those conditions, but I felt as if I knew exactly how he felt -- awkward, uncomfortable, stifled, yet eager and hungry for knowledge.

I wondered where he is now, if he is now. An old but new thought crept into my mind: We are the world. We are one world. For the first time in my life, Africa truly felt like the motherland. It had nothing to do with black pride and everything to do with what I saw in the eyes of that little boy: myself.

If nothing else, I expected my time in South Africa to be one of intense healing and self-acceptance -- the latter because I was already beginning to feel more comfortable in my own skin. It was partly because for the first time in years, when a nonblack person looked at me for too long, I actually had to wonder why. It wasn't because they so seldom saw people with my coloring (as had been the case in Buenos Aires, Melbourne and Bangkok, all of which I'd called home at various points during the seven years since I'd left New York City). It wasn't out of curiosity: "Is it true what they say about black men?" It was likely for something that was uniquely me and mine only. That was the self-acceptance part.

The healing part, however, had nothing to do with white people and everything to do with black people, with whom I'd had a life-long complicated relationship. It began when I was 4 years old, and my family moved from the U.S. Virgin Islands to Kissimmee, Florida, on the U.S. mainland. We eventually settled in an all-black neighborhood, and despite the physical similarities I shared with our neighbors, I probably wouldn't have felt more like an outsider had we ended up in the whitest community in town.

The racism I felt coming from a certain segment of Kissimmee's white population couldn't compare to the racism and xenophobia I encountered from portions of the American black community that resented my family and me because we were black and foreign. They called us "noisy Jamaicans" because in their inaccurate book, the Caribbean equaled the land of reggae and Rastafarianism.

We spoke with strange accents and kept to ourselves. Who did we think we were? What did we think we were, better than them?

The white racism directed toward me while I was growing up in Kissimmee was contained to strictly verbal cut-downs. It never touched me physically. "I smell nigger" coming from rednecks on the playground messed with my 11-year-old psyche in dangerous ways, but the black-on-black racism left physical as well as emotional scars. It scared me so much more. When they weren't sure their words were getting to me, the black kids who picked on me started picking up sticks and stones.

The physical bruises healed, but the emotional ones never did completely. It wasn't until I went to college at the University of Florida in Gainesville that I finally escaped the emotional and physical cruelty. For the first time in my life, the majority of black Americans I met accepted me and didn't make fun of me. If I eventually overcame the fear and resentment of black people that was borne from the way some of them treated me in my youth, I never forgot it completely. It continued to haunt me, contributing to the racism that I myself harbored toward my fellow black man.

But in South Africa, being around such a large and diverse black population, I sensed something shifting inside of me. I felt a certain camaraderie with black Africans, a comfort around them that I'd never felt around blacks anywhere else. I didn't know if they were able to look at me and tell I was from somewhere else, but when I opened my mouth to speak, I couldn't imagine they would ever ridicule the Caribbean accent that I never quite lost. They spoke English with exotic accents, too!

That's not to say they didn't acknowledge our cultural differences -- when Solly, the driver who took me from the Saffron Guest House to the Apartheid Museum, explained the local housing situation and used the word "ghetto," he started to define "ghetto" and seemed surprised that I already knew the meaning of the word -- but it was done with the utmost respect and acceptance. I didn't know how far that respect and acceptance would extend into other aspects of my personal identity, but the fact that I saw several gay couples walking down 7th Street in Melville holding hands, without onlookers so much as flinching, was encouraging.

Disconcertingly, with my burgeoning newfound appreciation and acceptance of my skin color came a different kind of awareness of it. It crept up on me every time I sat down in a restaurant in Joburg. Most of the waiters who served me were black, and when I went from restaurant to restaurant on 7th Street and saw the mostly black staff, it was hard for me not to feel pangs of guilt.

Were the owners, like the ones at Lucky Bean beside Saffron Guest House, white? Did the black employees spend hours commuting to and from townships like Soweto to earn minimal wages? Who lived in all the beautiful houses in Melville? In my new black fantasy, the black employees worked for black bosses who went home at night there, not to the poor outskirts.

I hated that I was even thinking along those lines, which was something I had never done in the United States because the division of labor in the restaurants I went to there didn't appear to be determined along white-black color lines. Most of the people who served me were white, and I never wondered where they lived.

It didn't matter that the clientele in most of the places in Melville was largely black as well, though it mattered more when the clientele was mostly white. I left Joburg after five days there, before I could figure out why white people in Melville flocked to certain places on 7th Street and not to others, but I was even more perplexed by my looming color overawareness. Why did it matter so much to me?

I'm still trying to process that aspect of my evolutionary process and what I can only describe as my personal version of white liberal guilt, the seeds of which may have been planted on the way back from the Apartheid Museum when Solly explained the difficulties that blacks in Joburg continue to face when applying for white-collar work. I've never thought liberal guilt looked particularly good on white people, and it clashes with my complexion.

I'm owning it, though, which might the first step in conquering it. I hope my ongoing evolution in South Africa (specifically Cape Town, where I arrived after Joburg and where I will be based at least through January of 2015) will lead not only to complete comfort in my own skin but perhaps, at last, it won't matter to me what color anyone else's is either.