Last week, 8-year-old Jmyha Rickman was handcuffed and held by police for two hours after throwing a temper tantrum at LoveJoy Elementary School in Alton, Illinois. On April 13, 2012, 6-year-old Salecia Johnson was handcuffed and arrested in her principal's office and taken to a local police station in Milledgeville, Georgia for having a tantrum in her elementary school classroom. In May 2010, 13-year-old Olivia Raymond was arrested, accused of felony theft, and suspended in Chicago after finding her teacher's sunglasses and attempting to return them to her. In September 2005, 14-year-old Shaquanda Cotton was arrested and later sentenced to up to 7 years in prison for shoving a hall monitor.

These are just four publicized examples of the hyper-disciplining and controlling of young black girls that recurrently takes place within the confines of the classrooms and hallways of many of our nation's schools--incidences reflecting conditioned responses to the stereotype-driven "threat" and fear of black and brown bodies, particularly those of the mythical "angry black woman," who functions as a walking, breathing embodiment of a threat to patriarchy. Oversimplified stereotypes once used to justify the rape and assault of black women during chattel slavery have trickled down to the bodies of our daughters, granddaughters, nieces, and little sisters, who are disproportionately disciplined in schools for being too "loud," "unladylike," "uncontrollable," and "defiant." Social justice advocate Monique W. Morris notes: "The behaviors for which black females routinely experience disciplinary response are related to their nonconformity with notions of white-middle class femininity, for example, by their dress, their profanity, or by having tantrums in the classroom."

In the most recent example, 8-year-old, 70-pound Jmyha Rickman was handcuffed, hauled in the back of a police squad car, and taken to the local police station after throwing a temper tantrum in class. Jmyha was reportedly upset after her requests to use the bathroom were ignored. Instead of contacting a parent or guardian, school staff called the police, who restrained the little black girl donning ponytails and pink hair ballies. "Her eyes were swollen from crying," Nehemiah Keeton, Jmyha's guardian, tells KMOV-TV, "and her wrists had welts on them and they cuffed her feet too." Alton police contend that Jmyha was put in a supervised juvenile detention room at the police station.

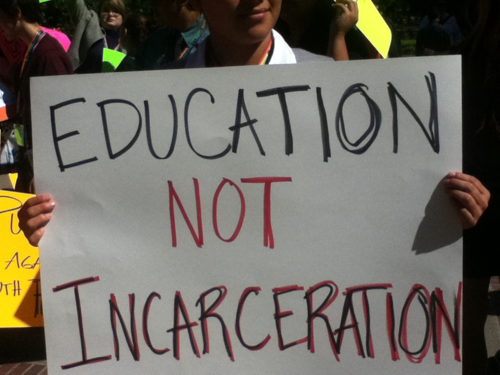

Regardless of the room in the police station in which a prepubescent girl was forced to sit and cry in while wearing shackles, the excessive, adult-like punishing of Jmyha Rickman is part of a broader problem manifesting in this current neoliberal moment, in which the needs of the market are met at the expense of democracy, public education, and responsibility toward the future. We are in a moment when many students of color are more likely to be policed, punished, and harassed in school than educated. Often framed as the "school-to-prison pipeline," our debased education system is working in collaboration with the growing prison system to hyper-surveil and criminalize youth of color. Throughout the United States, black and Latino youths are disproportionately suspended, arrested, and expelled--these disproportional rates reminiscent of the disparities in incarceration rates of black and brown bodies. In fact, according to the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights, African-American students are over three and a half times more likely to be suspended or expelled than their white counterparts, and over 70 percent of students involved in school-related arrests or referred to law enforcement in the 2009-2010 school year were African-American or Hispanic.

But, what happens when we gender the school to prison pipeline? When we racialize gendered violence and gender racial violence? When we focus on our little black girls being labeled a "problem" and thrown into detention and detention centers, prisons, and the backseats of cop cars in the middle of the school day?

While there is a growing body of literature on the disproportional exclusionary discipline (e.g., suspensions and expulsions) and over-incarceration of black and Latino youths, the unique ways in which black girls are affected by school-based punitive measures and instruments of surveillance (i.e., "zero tolerance" policies, metal detectors, law enforcement in schools, etc.) are often left out of the discussion. As noted by renowned legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in "Race, Gender and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Expanding Our Discussion to Include Black Girls," a report published by the African American Policy Forum, "the 'pipeline' metaphor fails to both capture and respond to the unique set of conditions affecting black girls today."

We must not forget about our little black girls, who continue to be invisibilized in classrooms, media, policies, and mainstream society. Today, black females represent the fastest growing segment of the juvenile justice system, as well as the most dramatic rise in middle school suspension rates. Schools have become hostile learning environments for our new "angry black women," with data showing that every one in ten black girls was subject to an out-of-school suspension during the 2009-2010 school year. Studies also show that black girls who speak out in class tend to receive negative feedback from their teachers, particularly if the teacher is white.

We cannot wait like the rest of America for moments such as Columbine and Sandy Hook to care about the violence occurring in our schools, as little black girls like Jmyha and Salecia are being detained and labeled "criminals" when they should be in class learning their multiplication tables and the significance of their unique black girl standpoints. Nor can we afford to continue to focus solely on the plight of black boys and men with the hope that these efforts will somehow impact the lives of our young black girls and black women. In the words of June Jordan: "We have remained bystanders while the compulsory public school system of Amerika proceeds to denigrate and punish the most innocent, beautiful purveyors of our black language: our black children. They continue to suffer an indefensible abuse that has become traditional."

We must look at the circumstances surrounding the modern-day policing of black youth with fresh eyes if we hope to address and alleviate the challenges facing black girls and women in today's society, and stop allowing constructed assertions of their purported deviance and pathology to be used against them. An intersectional lens and interventions that fully apprehend the distinctive impact of surveillance, violence, punishment, and stereotyping on the lives and experiences of our black girls are necessary if we truly seek to end the war on women, the war on "angry black women," the war on blacks, the school-to-prison pipeline, and all other institutions of inequality.