John Waters: There's something perpetually endearing about a guy -- now 67 -- who refuses to grow up and with a sensibility that makes most hipster-denizens of Williamsburg absolutely prudish by comparison. He's continued to keep himself fresh and square in the public eye. His one-man show, A John Water's Christmas, which he's taken on the road in past years always finds a ready audience willing to share in his bonafide hatred of all things unselfconsciously kitschy: think living crèches and inflatable front lawn Santas.

Like the common cold, you can't entirely avoid the Christmas spirit and when Waters feels it coming on he responds with his own corrupted take on the greeting card which always features himself in some distorted, seasonal representation of Santa or the Virgin Mary holding the Baby Jesus. It's probably the one card that remains on my mantel way after those Hallmark monstrosities find their rightful place as tinder in the fireplace.

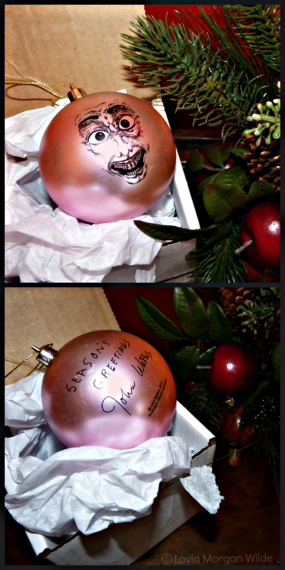

However this year his seasonal greeting came in a box not in an envelope, and lo and behold it was a ball: a Christmas ornament with Water's caricature on one side and a handwritten greeting on the other.

Now, truth be told, I'm on Water's Christmas list for a specific reason and that's because we share an interest in a nearly-forgotten film producer by the name of Kroger Babb.

Babb, a self-described "country boy with a shoe shine," was a back-slapping, jovial Midwesterner who took to the roads in the 1930s as part of a group of hucksters known as the "Forty Thieves." They'd cruise through rural America in loudspeaker-equipped jalopies packing a projector, film prints and a screen drumming up audiences in small towns with taboo cinema offerings that ran the gamut from white slavery to child brides, to narcotics addiction to footage of live births. Production values? Non-existent. But who cared when you had a paying audience titillated with the subject matter and enthralled with the possibility of escaping from their depression-era miseries for an hour or two?

Babb quickly realized that with a bit of marketing alchemy he could turn goose dung into golden pellets and made a beeline back to his hometown, Wilmington, Ohio, where he bought an old Victorian and transformed it into the world headquarters of Hygienic Productions. The aim of Hygienic was to produce and distribute the kind of exploitation entertainment that usually fell under the rubric of "dirty films." In 1943, he hit pay dirt with Mom and Dad. The story line was simple: a blushing, albeit naïve, high school beauty, Joan, from a mainstream family tries to obtain the basic facts of life from her prudish mother. Mom recoils in horror when asked if she could supply some sexually enlightening material euphemistically known at the time as "hygiene manuals." No dice. Then -- surprise, surprise -- uneducated Joan proceeds to fall for a fast-talking pomaded Romeo who plies her with alcohol, and quicker than you can say "I'll have another" is made pregnant by said Romeo who then conveniently dies in a plane crash.

Babb spun this as a morality tale with a message; after all if Joan had been allowed access to sober well-written sex education manuals she wouldn't have found herself with a bun in the oven and no prospects for a decent life. To make sure that all those paying good money to see the film got the message, Babb employed a "fearless sex commentator" by the name of Elliot Forbes to deliver an earnest facts-of-life spiel during intermission. At the close of the lecture, not missing a beat, a gaggle of Hygienic employees fanned out through the aisles hawking genuine sex manuals for a buck apiece. The manuals were actually penned by Mom and Dad's screenwriter, Mildred Horn (later to become Babb's wife and partner in crime). The second part of the show would then unspool and it was a real grabber: graphic educational representations of a penis-in-vagina followed by footage of a live birth (Babb had gotten the film from the U.S. Army's medical corps). If the attendees were male (the film was shown to gender segregated audiences) real penises in various states of venereal decay were on graphic display; after all, a lack of sex knowledge can also wreak havoc on the crown jewels.

Mom and Dad teams crisscrossed the country. At one point a couple dozen "Elliot Forbes" traveled the circuit simultaneously and Babb would outfit each road show with fake nurses to greet moviegoers in the lobby and park ambulances outside to spirit away any fainting attendees who fell prey to repressed sexual impulses. There was even an African-American unit with its own compliment of Elliot Forbes which included, at one point, Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens.

Censorship battles followed the film everywhere. Babb saw this more as an opportunity than a problem. Catholic priests formed human chains to prevent people from walking into theaters and local authorities would bulldoze sidewalks and sometimes ticket booths from the front of theaters to discourage attendance. Needless to say, this only created more interest and ticket sales. In fact, Mom and Dad, when all was said and done, made anywhere from 40 to 100 million dollars despite repeated condemnations by organizations like the National Legion of Decency and the American Legion and continued to play well into the 1950s (the film had its first premiere in New York City in 1957). Time magazine, in a 1949 review, estimated that one out of every 10 people in the world had seen Mom and Dad and proclaimed that the film's message was so pervasive and ubiquitous that it "left only the livestock unaware of the chance to learn the facts of life."

Showmanship was Babb's middle name and to make sure everyone knew, it took to calling himself "Mr. Pihsnamwohs" (hold it up to a mirror). He even emblazoned the side of his rickety corporate airplane with the moniker.

One of those estimated millions who caught a gander was a young Catholic school student by the name of John Waters. When the film landed in Baltimore, Waters recalls the hell and brimstone admonitions of the nuns: Set foot in a theater running Mom and Dad and prepare to share Satan's bed and broil in hell's everlasting fires. Needless to say, 10-year-old Waters not only snuck into a screening but spent endless hours musing on what it would be like to own a "dirty" movie theater, and like a young Martin Scorsese creating story boards for imaginary films, Waters would dwell on ideas for new Mom and Dad ad campaigns.

Babb died in 1980 but a few years after I was lucky enough to meet Babb's widow, Mildred. Together with some colleagues, I had set out to dig up more information on this forgotten film producer (I had come across some cryptic references to him in various publications). Mildred was eager to talk and talk she could. Then in her 80s she went full throttle, non-stop, waxing poetic about the shock value of her shared ventures with Babb; spinning hilarious stories delivered with proverbial rapier-sharp wit and to top it off she could still drink myself and my colleagues under the table. There was a simpatico connection cemented by our desire to resurrect Babb from cinema's dustbin of history. She responded by laying all sorts of memorabilia on us, including original scripts, posters, copies of Mom and Dad sex manuals, copies of Babb's films (including a 35mm nitrate print of Mom and Dad); even a bust of Kroger sculpted by the daughter of longtime friend and fellow promoter, Colonel Sanders. A subsequent research trip to Babb's hometown of Wilmington in 1989 netted us even more valuables (he was still a well-loved and remembered figure) including boxes of Mom and Dad premiums -- match books and medicinals -- branded with the film's title. But the pièce de résistance was the actual banner that hung outside Babb's Wilmington headquarters proclaiming "Hygienic Films: Producers, Exploiters, Promoters."

Television eroded and eventually killed the film exploitation business but not before Babb was able to make additional contributions to American hucksterism with epics like The Prince of Peace (1949), One Too Many (1950), Why Men Leave Home (1951), She Shoulda' Said "No!" (1954), and Babb's own paean to great literature, Kipling's Women (1960), a nudist rendition of the "The Ladies."

There was one film that Babb regretted not finishing. Father Bingo never went beyond the concept stage. It was going to be an "expose" of church hall games of chance and a corrupt parish priest who manipulates the outcomes. Babb allegedly boasted that this film would end up being "the best snow job of my life."

John Waters still waxes poetic about Father Bingo and, like myself, deeply laments its unfinished passage into cinema oblivion. Given the many controversies surrounding the Catholic church it might have stood as a fitting Nostradamus-style tribute to the memory of a great film producer.

A few years back I sent Waters some Babb memorabilia that included an original Mom and Dad sex manual and a Mom and Dad branded premium (I forgot whether it was the burn or the rectal ointment). I've been on Water's Christmas list ever since. We've also discussed working towards the noble goal of helping Kroger Babb find his rightful place in the annals of film history.

It's a natural for Waters. Clearly he shares some of Babb's DNA.

Joel Sucher is a filmmaker with Pacific Street Films and a contributing blogger for Huffington Post. Currently -- no surprise -- he's working on a documentary and feature film project focused on the life and times of Kroger and Mildred Babb.