There were maybe ten of us meeting with him in the room that day, spread out in a circle, telling him about what it was we wanted to do, and listening to him tell us who he was and what sorts of things he'd done. The meeting went on for well over an hour.

We were all teenagers; he was in his forties.

We were a group of high school kids who had decided we wanted to start our own high school, a place where we could really learn. He, a long-limbed, droopy-mustachioed writer and educator named Julian F. Thompson (today an accomplished novelist), was the latest in a procession of candidates we were interviewing for the position of director.

(Yes: we, the kids, were interviewing the grownups. That right there tells you these were no ordinary grownups.)

At the end of our meeting, we all spontaneously crouched together in a huddle, Julian included, our arms wrapped around each others' shoulders, then burst apart with an ebullient team cheer. We exited the room laughing.

I remember marveling all that afternoon at that huddle, with its team shout trailing off into laughter, and how natural it felt. All our other candidates were wonderful people with fascinating backgrounds and delightful personalities, each strongly sympathetic to our cause.

But we hadn't ended any of those other interviews with a huddle and a shout.

This man wasn't one of us, exactly (he was an adult, after all), but we instinctively knew, somehow, that he spoke for us.

The fact that we were looking for a director in the first place was somewhat paradoxical. We were, after all, starting a school created by teenagers, for teenagers, where we could study whatever we wanted, without requirements or restrictions. So why did this group of kids who didn't want to be told what to do by anyone make our first executive act the "hiring" of a grownup?

Because we knew we needed a leader.

We needed someone who could stand before a gathering of dubious adults and articulate what it was we were doing, and why. We needed someone who could help with the massive amount of fund-raising it would take to generate the cash flow to get this thing off the ground, and the experience to manage that cash flow. We needed someone to help find the building we would use and, once we discovered that using it would require our securing a zoning variance from the city, to go before a public meeting of the zoning board to persuade why they should bend their codes and regulations for this motley crew of 17-year-olds.

We needed someone who could speak for us and act for us. Most of all, we needed someone who got us.

We needed someone who didn't redefine our aims and purpose to fit the contours of his own ideas and priorities, but who saw us through lens of our own best selves. Who could help provide direction when we needed it, correction when circumstances called for it, and unqualified support at every turn. Who could see who we were, in all our imperfections and in the perfection of our aspirations, and was fully on board.

An hour and a half of meeting and talking with Julian told us, this might be the guy.

The unprompted huddle and shout showed us, this was the guy.

Julian had in the past taught at an exclusive New Jersey prep school. (Quite a different environment than the one we were proposing!) He told us about a teacher there whose colleagues all described him as a great teacher. "Terrible with kids," they would add, "but what an amazing teacher."

What they meant, I suppose, was that the guy was a phenomenal lecturer. A phenomenal lecturer who happened not to care much for kids.

Julian found this both horrifying and hilarious, and so did we.

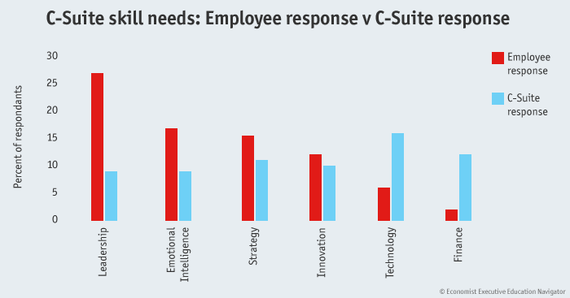

I thought about Julian's story the other day when I bumped into a survey conducted by The Economist. A group of more than 4,000 C-suite executives (CEOs, CFO, COOs, et al.) were asked which, out of six specific skill sets, they thought they most needed to improve. These six skill sets included:

- leadership

- emotional intelligence

- strategy

- innovation

- technology

- finance

At the same time, the researchers also asked a group of the executives' employees where they thought the executives needed to improve.

The two groups' answers were fascinating.

(From "Your employees wish you were emotionally intelligent," by Natalie Baker, The Economist: Executive Education Navigator, Apr 5, 2016.)

On the skills 3 and 4, strategy and innovation, their answers were similar. The skills the employees most wanted to see improved, 1 and 2 -- leadership and emotional intelligence -- were the ones the leaders thought they needed least. And the areas they thought they most needed to work on, technology and finance, were the ones the employee group pegged as lowest priority.

The leaders saw their responsibilities as mainly technical -- much as that phenomenal prep-school lecturer no doubt saw his.

The people those executives were charged with leading saw their leaders' roles as mainly personal. Much as the phenomenal lecturer's students would have responded, I suspect, had they been asked.

Julian's story was in the back of my mind not long ago when Bob Burg and I wrote The Go-Giver Leader. In that tale, there's a character who says at the end of the story:

"Whatever great parenting looks like, it is not about the parent. Great teaching is not about the teacher. Great coaching is not about the coach.

"And great leadership? Well, you can fill in that blank."

On that warm New Jersey day, our little committee of teens filled in the blank. Great leadership, we discovered, is not about the talk and the résumé.

It's about the huddle and the shout.