Politicians, economists, analysts, writers, bloggers, reporters -- everyone has an opinion on how to fix our economy. Manufacturing has emerged as a viable solution. With endless articles, reports, theories, blog posts, and tweets that examine its value on the U.S. economy, there is no doubt the manufacturing industry would create jobs, keep money in the U.S. economy and perhaps stimulate our economy in a way that we've yet to see.

However, the big question now is how?

In Part I, apparel manufacturing is explored as one of the avenues of manufacturing that is overlooked. Apparel is one main product that we all have it common. We all wake up every day and put on clothes, whether you're a doctor, police officer or an architect. History validates it's potential as a strong solid solution.

During WWII, every soldier's uniform, every parachute and the linens used in military hospitals were made by the hands of Americans. The fabric that created these sewn products was grown and processed by Americans. We were truly an independent country that supported and sustained itself.

In the 1950s, the U.S. apparel manufacturing sector was the driving force of the economy, employing more than a third of the private sector workforce. The total number of U.S. apparel manufacturing jobs peaked in 1979 at 19.5 million. The Internet arrived mid-1980s which reformed the way businesses communicated, making overseas production a simple email away. Today, the apparel manufacturing industry accounts for less than 10 percent of the U.S. workforce. The statistic, "98 percent of all apparel worn by Americans is imported," can not be ignored nor disregarded. Apparel and other household fabric products are too strong of a product category and too present in our everyday lives to not research a strategy to reintegrate it back into our economy. But there is a bigger problem at hand -- a basic economic oversight that will greatly affect the path of success for a manufacturing resurgence, mainly apparel and household goods.

A powerful force behind apparel manufacturing in the U.S. throughout our history relied on our country's size, our land, and our ability to make the most from it. In past 200 years, cotton has been an economic answer for both the South and the rest of our country, employing families, towns, and entire regions. From the cotton fields, the bales of cotton were either sold or traded at a cotton exchange, or sent directly to textile mills to be processed. Most textile mills were located in the New England area, where great technologies to spin, weave and print on the fabric emerged.

According to the Census of Agriculture, U.S. cotton farms has dropped by 98 percent over the last fifty years, from approximately two million cotton farms in 1930 to today about 18,591 in 2007. Even in the last ten years, it's decreased drastically in number, 24,805 in 2002.

But the facts do not match up.

Annual business revenue stimulated by cotton in the U.S. economy currently exceeds $120 billion, making cotton America's number one value-added crop. The United States is the second largest producer of cotton in the world, but also the largest exporter of cotton in the world, shipping roughly 60 percent of its yield. So while we proudly proclaim ourselves as the second largest producer of cotton in the world (which makes sense as we're the third largest country in the world), we export it before we can even fully utilize it efficiently. China, on the other hand, produces more cotton than the U.S., making it the largest producer of cotton but exports little to none.

Let's bring in a second issue -- another over-discussed, highly criticized issue that directly correlates with the decline of U.S. manufacturing: the U.S. Trade Deficit.

The country we import the most from is China, with whom we hold the highest trade deficit. Besides the obvious categories of world imports -- iron, steel, petroleum, automotive, one category is far too vague, "consumer goods." That's a pretty broad classification. We consume quite a lot in America. In fact, we're known for it. iPods and computers are the obvious products under consumer goods but it deserves a more concise breakdown.

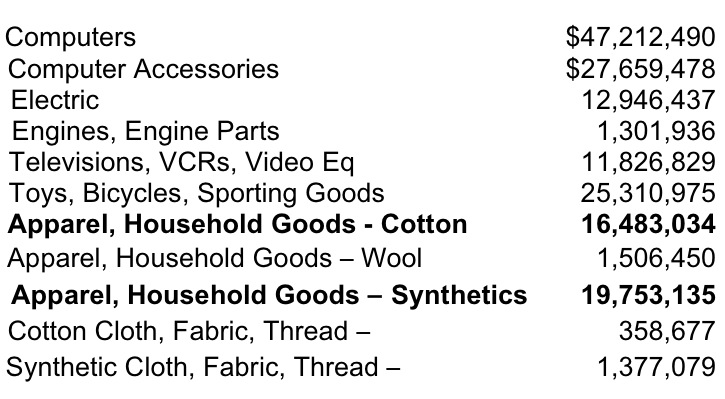

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2011, U.S. Imports from China, classified as Consumer Goods, break down in dollar value to roughly.....

The numbers for apparel and household goods are comparable to those of computers. Shocking. To import such highly technological pieces of equipment makes sense, but something so simple and temporary as apparel? Unnecessary. And If 98 percent of the apparel Americans wear is imported, yet we're the number one exporter of cotton, there is still a key factor to this equation that we are missing.

If you visit cotton.org, the website for the National Cotton Council, they proudly state, "Overseas sales of U.S. cotton make a significant contribution to the reduction in the U.S. trade deficit."

But in reality, our exportation of cotton as a raw product is fueling their level of capacity in textile and apparel products to export. And leaving ourselves in a pretty dangerous situation.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the top four most rapidly declining industries are all related to textiles, fabric and apparel manufacturing. It doesn't stop there. Look at the top ten, eight are textile-related. It's devastating. An entire industry is on its way to extinction. The one product we all have in common, the simplest of products we handle on a daily basis, consisting of simple seams and stitches, is apparel, and we will soon lose the ability to produce -- and manufacture textiles and apparel, forcing our country into a dangerous dependency. Embarrassingly ironic, as we were the ones who invented the cotton gin.

We've become so accustomed to importing apparel as finished products and goods, yet so proudly exporting the raw crop of cotton, that we've have forgotten the hundreds of smaller secondary industries that are directly affected by the decline of U.S. manufacturing. From zippers and buttons, to the computer-aided design programs that digitize industrial sewing machines and inventory management processes that regulate the efficiency of textile mills, these smaller industries thrive only when apparel manufacturing does. And with each smaller industry, jobs manifest. From wholesale fabric sales reps to the onsite machine techs, business to business -- all relying on each other to succeed. By allowing our country to stay excessively dependent on other countries to do the majority of simple tasks -- producing, creating, developing, sewing -- we are no longer independent. If one day China stopped the exportation of all apparel, would we possess a workforce skilled enough to sustain ourselves? No. Just check that 'rapidly declining' chart above.

So why is that section of 'rapidly declining jobs' such an alarming red flag - a danger signal? To the normal office worker, stockbroker, politician, teacher or nurse, it wouldn't be. But to someone as young, yet inundated in this apparel manufacturing industry as myself, it's a call to action.

To date, our company, Jolie and Elizabeth, a women's contemporary apparel design company, has manufactured over 4600 dresses, and put $350,000 back into our economy. And our company isn't even 3 years old yet.

Our apparel manufacturing facility is located in the South -- in New Orleans -- where we're surrounded by cotton fields and the history and pride of a region once driven by the cotton crop. But when we attempt to find simple cotton broadcloth, it is impossible. Well, since cotton is such a booming industry, bringing in $120 billion in annual revenue then where is it? If the U.S. is the second largest producer of cotton in the world, then why can't we buy U.S. grown, U.S. spun cotton fabric? Or any fabric grown and processed here in the U.S.?

Next, we reached out to various Cotton Boards and associations in the region, who proudly boast that cotton is at an all-time high, technologies are as advanced as ever, and cotton is America's number one value-added crop. But their reply to me is that, due to a lack of domestic textile mills, there's no cotton fabric, sorry. When I asked how many fabric mills still exist today, their reply is clear indication of an economic oversight -- forty. There are approximately 40 fabric mills left today.

So how can we possibly encourage an American manufacturing renaissance when there are no materials to work with? And how did we get here? What happened?

One contributing factor is the engineering innovations of John Deere. In just 2007, John Deere developed the latest version of an industry -- exclusive cotton module builder. Just as a tractor would, this machine plows straight down the field, and all in one step, harvests, rolls and packages the cotton, from the plant to a bale, ready to export. Farmers can work faster, produce and export cotton bales at record levels. Despite the fact that U.S. cotton farms have dropped by 98 percent over the last fifty years, from two million in 1930 to about 18,600 today, we haven't lost farms, we've just consolidated and innovated. Instead of hundreds of small family run farms, where cotton is picked by hand, we have massive industrialized cotton farms, whose output far exceeds that of even 20 years ago. But by packaging cotton bales straight from the farm to the loading dock to export, we've eliminated entire industries. It would seem that we only farm cotton with the sole purpose to export. To lose the ability to take our own cotton crop, spin it into a fiber then process it into a textile is far more debilitating to our economy that we can imagine. It isn't John Deere's responsibility to think of this long-term effect nor is it the farmers. Contracts for both fabric and apparel manufacturing by apparel design companies moved from South Carolina to India, leaving textiles mills and apparel factories empty handed.

And this is where China is smart. We export over 60 percent of the cotton grown, yet import 98 percent of apparel. Subsequently, our textile and manufacturing industries (i.e., jobs) are diminishing. The largest producers of cotton are China and India, producing almost double the amount of cotton that we do but retaining 100 percent of it. And who's China's biggest customer? We are.

We export the majority of our own crop, only to have China process it into a textile and sell it back to us, both as bolts of fabric and in the form of supremely cheap apparel in mass quantities (Think Walmart, Forever 21 and well... the majority of apparel, linens, bed sheets, curtains and the like available to purchase in America.) So cheap that it falls apart and we keep running back for more.

So when apparel designers, such as myself, begin to source fabric, we are forced to purchase through a jobber, who holds contracts with various factories overseas. We pay $4/yard for simple broadcloth. That $4/yard should be $1/yard and should come from our own backyard. Instead we're puppets in a larger storyboard, exporting only to import, over-consuming only to be left jobless. We used to be creators, innovators, and prided ourselves on being a strong, self sustained independent country.

With over 17 universities below the Mason-Dixon line, that graduate over 250-plus a semester in apparel design, apparel manufacturing and textile design, where are these graduates going to work? More importantly, the foundation for the future of these young hopefuls is currently on the 'rapidly declining industries' list. So while U.S. manufacturing is the topic of now, the movement every politician, economist, and reporter has opinion on, it is up to our president and our government to organize the great minds of these apparel, textile, manufacturing and agriculture industries to create an American manufacturing plan -- not incentives, but a plan of action. And without materials, how can American manufacturing possibly make an impact and long-term comeback?

This article is the second of a series, focusing on American manufacturing and its potential as a catalyst for economic recovery. Jolie Bensen can be reached at jolie@jolieandelizabeth.com or at http://www.jolieandelizabeth.com