What do Google CEO Eric Schmidt, the Supreme Court of the United States and golfing giant Tiger Woods have in common?

Privacy.

More specifically, how we define privacy in our texting, tweeting, Facebooking, YouTubing, Googling era.

Earlier this month, after Sprint, Verizon and Yahoo were blasted following revelations that they've shared customer data with the authorities, Google's Eric Schmidt declared in an interview with CNBC: "If you have something that you don't want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn't be doing it in the first place." Boom! It was as if Schmidt had planted a bomb in the blogosphere. And he wasn't done: Since Google is subject to the country's Patriot Act, "it is possible that information could be made available to the authorities," Schmidt went on. Ka-boom! Quite a statement coming from the head honcho of the Internet's biggest company. The reaction was swift and damning. Wrote John C. Dvorak of Market Watch: "For a chief executive to make what amounts to a threat to its users is absolutely astonishing."

And it's not just about Google. It's about privacy in our digital world at large, where data is shared in computers and phones, where information spreads from one social network to another. The issue has finally reached the highest court in the land. As the New York Times reported Monday, the Supreme Court will decide whether the Ontario Police Department in southern California violated the constitutional privacy rights of Sgt. Jeff Quon. The department inspected Quon's text messages that were sent and received on a government pager -- many of them "sexually explicit in nature," The Times wrote.

In an interview, Marc Rotenberg of the D.C.-based Electronic Privacy Information Center told me that Quon's case is "without question the most important online privacy case, addressing all sorts of questions that we've all been grappling with." Rotenberg, one of the leading experts on digital privacy rights, defined what he calls "modern privacy" in a blog for HuffPostTech in September. First, "modern privacy begins with the understanding that personal information will be widely accessible," he wrote. In other words, we all leave digital footprints -- in our blogs, Twitter feeds and Facebook updates, etc. Second, "modern privacy is about what happens to information once it's held by others -- whether it's a government agency, a bank, a cell phone company, or a social network site." Translation: It's not about the technology, it's about how people use the technology. It's about our behavior.

More than a decade ago, Rotenberg predicted that "privacy will be to the information economy of the next century what consumer protection and environmental concerns have been to the industrial society of the 20th century." He was absolutely right. And privacy in our information economy extends far beyond our own individual, ordinary lives. It also impacts how we view others.

Which brings us to Tiger Woods, arguably the most private of our sports stars.

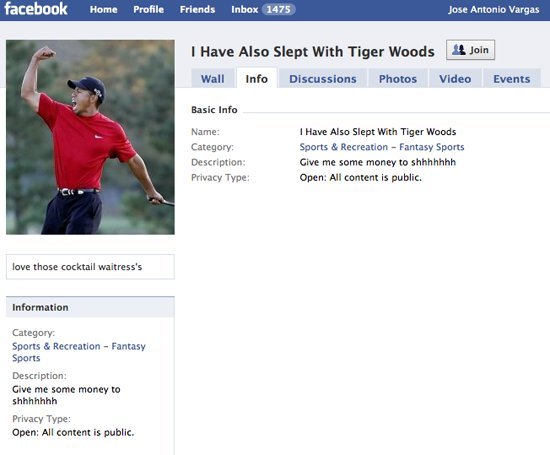

Last Friday, Woods posted a 165-word statement on his site, apologizing to his family and fans for his "infidelity." The statement ended with, "Again, I ask for privacy..." But the moment Woods crashed his Cadillac Escalade and hit a fire hydrant nearly three weeks ago, his privacy was gone. An unstoppable flood of information -- a hurricane, really -- continued circulating online: the list of women, the text messages from his phone, the voice mail he allegedly left to Jaimee Grubbs. And we -- yes, we , you and me -- started spreading them around. On Twitter, where #tigerwoods has been a popular hashtag since Thanksgiving weekend. On Facebook, where we posted the news and shared it with our "friends." There's even a Facebook group called "I Have Also Slept With Tiger Woods," and it has more than 139,000 members.

The relationship between athlete and fan, between celebrities and the people who follow their every move, has changed. In the past, celebrities dealt with only the media -- mainstream news organizations, from Sports Illustrated to 60 Minutes, but also the tabloids. It was the National Enquirer, after all, that published the story of Woods' alleged affair with nightclub manager Rachel Uchitel. But now, in addition to traditional media, celebrities are dealing with the rise of social media. That means us. As we pass around each nugget of Woods-related information -- may it be gossip or innuendo, serious or silly -- we chip away at the very privacy that Woods has asked for.

Privacy, as Woods probably defines it, is dead. Not even a billionaire athlete can afford to buy it. But "modern privacy," as Rotenberg explained it, is just beginning.

Rotenberg said: "This will be the defining issue of the next decade" -- whether you're Tiger Woods or just an ordinary citizen tweeting, Facebooking, YouTubing and Googling away.