Much attention is being paid these days to the role that genetics plays in health and illness. The Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, succeeded in identifying all of the genes in human DNA. That achievement, combined with ongoing research into the relationship between genes, illness, and disease, has given rise to a whole new field of medicine: "genomic medicine." The University of Connecticut Health Center, for example, where I work, recently announced that it is establishing a major research and clinical facility in conjunction with the Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine. The hope is that research will help us identify the genetic causes of disease, which may in turn lead to more effective treatment and/or prevention strategies.

To date, some of the more high-profile results of genomic medicine have centered around cancer. The actress and social activist Angelina Jolie, for instance, just made public the fact that she had opted to have a double mastectomy, to be followed by having her ovaries removed. Why? Because newly-developed genetic tests reportedly revealed that she had a genetic anomaly that raised her risk for cancer to an almost astronomical level. Rather than take that risk, she opted for this radical prevention strategy.

What About Addiction?

The idea that alcoholism (and perhaps other addictions) "run in families" is hardly new. Simple observation typically confirms that families rarely have only one alcoholic member. But does that fact imply that the causes of alcoholism and addiction necessarily are essentially in our genes? Given the current emphasis on genetic research and genomic medicine, it would be tempting to think that. It could even be tempting for people to conclude that since alcoholism is in our blood, so to speak, there is little that can be done about it unless and until genomic medicine discovers a cure. But is that true? Let's look at what we actually know about the genetics of alcoholism.

Probably the best information we have about the hereditability of alcoholism comes from studies of twins, and specifically those that compare identical twins with fraternal twins. So-called "identical" twins are monozygotic, meaning that their 23 chromosome pairs are identical. Accordingly, they look exactly the same. In contrast, "fraternal" twins, while sharing the same womb, have different chromosomes. To the degree that any mental or medical illness is genetically determined, that should be reflected in what is called "concordance" among identical twins. For example, if genes determine risk for cancer, there should be a very high concordance rate of cancer among identical twins.

In one of the largest twin studies ever conducted, researchers at the University of Washington and the University of Queensland followed a total of 5,889 respondents, including male and female twins. What they found is informative, not only for what it tells us about the possible genetics roots of addiction, but also about the options that people have when alcoholism "runs in the family." Here are some of the highlights:

- Among this large sample as a whole, as many as 32 percent of the men and 7 percent of the women would, at some point in their lives, experience alcohol dependence. In other words, problems with drinking, at least at some point in a person's life, are not all that uncommon.

What are we to conclude about whether alcoholism is in our blood? To begin with, it's clear that it is a common problem. That should hardly surprise us, given the extent to which our society promotes drinking.

Perhaps most importantly, even an identical male has only a 50 percent chance of becoming alcoholic if his identical twin is alcoholic, and a female twin has only a 30 percent chance. In other words, fully half of genetically identical men and 70 percent of such women will not share a common fate.

What to Do?

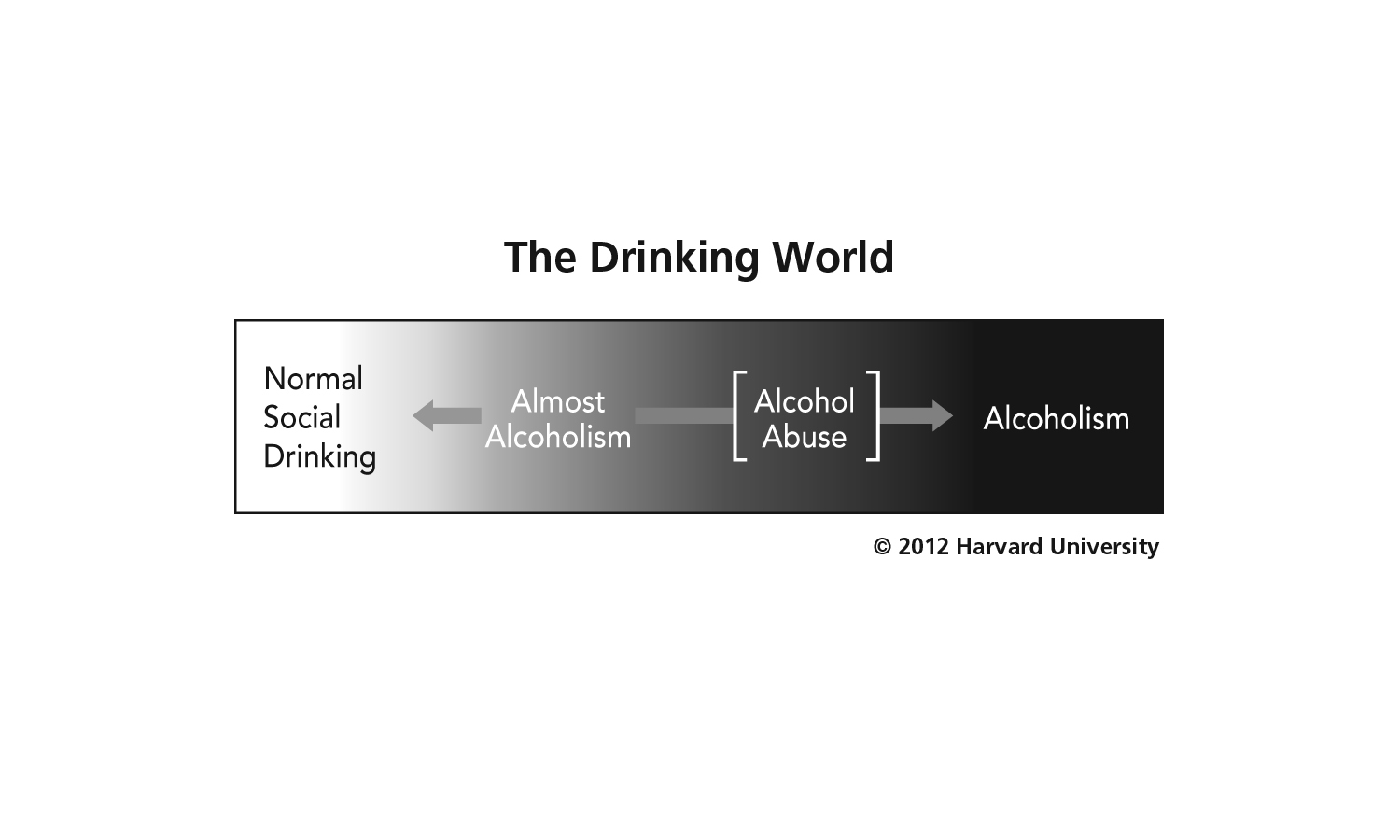

Obviously, it would be foolish to simply dismiss or ignore the fact that genetics appears to play some role in a person's vulnerability to alcoholism. That said, it's also clear that, at least as far as alcoholism goes, our genes are not our fate. In its newly-revised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the American Psychiatric Association has dropped its previous "categorical" definition of alcoholism (either you are an alcoholic, or you or not) in favor of viewing drinking problems as existing on a spectrum that ranges from abstinence and social drinking at one end, through what could be called a large "almost alcoholic zone" in the middle, to severe alcohol use and dependence at the other extreme. This paradigm shift in turn opens the door to viewing drinking in an entirely new (and less stigmatizing) way. That view is represented by the following diagram:

Based on what we know about the prevalence of alcohol problems in society, it would be wise for people to begin thinking about their own drinking behavior in terms of this spectrum concept. As opposed to feeling that they are "safe" as long as they have not become physically dependent on alcohol, they might begin to be more vigilant for subtler symptoms that result from drinking but that are typically overlooked when drinking is looked upon from the categorical perspective. Common among such symptoms are disturbed sleep, low-grade depression, reduced stamina, and hypertension. Twin or not, a person armed with this insight is then in a better position to make some choices about his or her drinking. The bottom line, then, may be that free will trumps genetics when it comes to alcoholism.

For more by Joseph Nowinski, Ph.D., click here.

For more on addiction and recovery, click here.