Sykes-Picot a Century Later

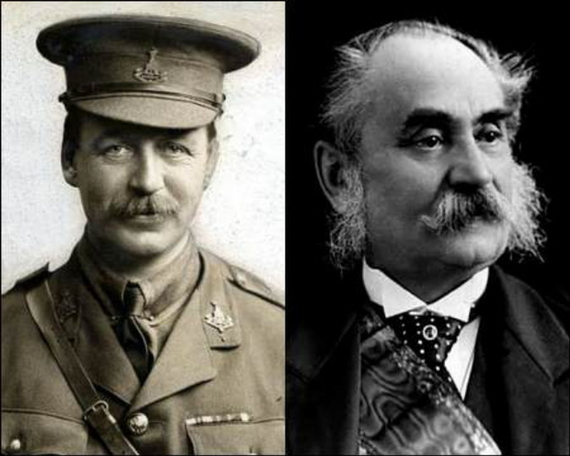

May 16 marks the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Sykes-Picot Agreement between Great Britain and France. Officially it was called the Asia Minor Agreement, but it has gone down in history as the namesake of its two principal negotiators--Mark Sykes and Francois Georges Picot .

The agreement marked the beginning of the imposition of European dominance over the Middle East, which would last for roughly half a century. It was the first exercise of European control since the First Crusade at the end of the eleventh century. This time, however, it covered virtually the entire Middle East, not just the thin strip of land from Edessa to Gaza that had hosted the Christian Kingdoms from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries.

The genesis of Sykes-Picot was varied. When the Ottoman Empire formally entered World War I as an ally of the Central Powers on November 3, 1914, Russia had been quick to demand British and French approval for substantial concessions from the Ottomans in the event they were defeated. Russia demanded "the city of Constantinople, the western shore of the Bosporus, Sea of Marmara and Dardanelles, as well as southern Thrace up to the Enos-Midia line," as well as "a part of the Asiatic coast between the Bosporus, the Sakarya River, and a point to be determined on the shore of the Bay of Izmit." Russia even demanded control of Mosul and the oil fields surrounding it.

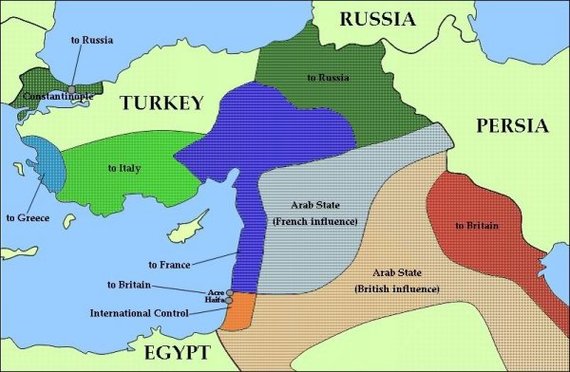

Original division of Ottoman lands between Great Britain and France set out in the Sykes-Picot Agreement

Original division of Ottoman lands between Great Britain and France set out in the Sykes-Picot Agreement

The Ottoman entry into the war came at a time when the Allies were reeling on the Western Front. The German advance into France had been checked only a few weeks before at the First Battle of the Marne, (Sept 5-12, 1914). Both sides were now engaged in the "race to the sea," as each army tried to outflank the other. In the process, as each side dug in, they created the system of trenches that would define combat on the Western Front for the next four years.

Great Britain and France readily agreed to the Russian demands, save for the one for Mosul and its oil fields. That concession was reserved for later discussion. At the time, neither Great Britain nor France could spare any troops for the new front, so engaging the Ottoman Army was seen as mostly a task for the Russian Army.

Sykes-Picot was motivated by the British and French desire to both block any further expansion southward by Russia, as well as an attempt to grab a chunk of the Ottoman Empire for themselves, especially the oil rich regions around Basra and Mosul. At this point oil had been discovered in Persia (Iran) and Mesopotamia (Iraq) and along the Caspian. The discovery of oil in the Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula would not happen until the 1930's.

The original agreement called for Mosul to be incorporated into the French zone, which would later be organized into Syria, and for Basra to be incorporated into the British zone. It would later be included in the League of Nations mandate for the newly organized state of Iraq.

The final boundaries would be revised multiple times by subsequent treaties. The Versailles Peace Conference (1919), the Treaty of Sevres (1920), its subsequent revision in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), the San Remo Conference (1920), as well as various League of Nations mandates, all changed the original division laid out in the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

Mosul for example, originally intended to be part of the French zone, was incorporated into the British Mandate of Iraq. In turn, London organized the North Iraqi Oil Company to exploit the Mosul oil fields and gave France a quarter stake in the company. The Golan Heights were originally part of the British Mandate for Palestine, but were traded to France in return for the region of Metula, in what is now northeastern Israel.

There were a variety of other side agreements as well, many of which would ultimately prove to be incompatible. These included, famously, the Hussein-McMahon correspondence, which assured that the Hashemite family would rule most of the region in return for their support in organizing and leading the Arab revolt against the Ottomans. This was the revolt that propelled an obscure British Lieutenant named T.E. Lawrence to fame as Lawrence of Arabia.

It also included the Balfour Declaration that declared, "his Majesty's government view(ed) with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people." That declaration was subsequently incorporated into the Treaty of Sevres and into the agreement governing the British Mandate of Palestine.

Italy, Greece and Armenia had all been promised substantial territories in Asia Minor in return for their participation in the war on the Allied side. Armenia, for example, would have received additional territory westward as far as Lake Van, a area also promised to Russia. Italy had been promised various Aegean islands, some of which were claimed by Greece, as well as control of the western and south central coasts of Anatolia around the city of Antalya.

Greece had been promised Smyrna and the region surrounding it--the city hosted a large Greek population. It had also been promised control of Constantinople and all of Thrace, both of which had also been claimed by Russia. Most of these concessions were subsequently cancelled by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

At Versailles, President Woodrow Wilson advocated for the creation of a Kurdish state, but this also was dropped in subsequent negotiations. So, too, were promises to the region's Assyrian Christian population for their own independent nation. Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, Russia's new Bolshevik government demanded that Great Britain and France honor the concessions that had been made to Russia back in November 1914. The Allies refused, arguing that the Bolsheviks had forfeited those concessions when they had signed a separate peace with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918. In retaliation Lenin ordered Pravda to print the text of the Russian copy of the Sykes-Picot Agreement in the Tsarist archives. That's how the world first heard of the hitherto secret agreement.

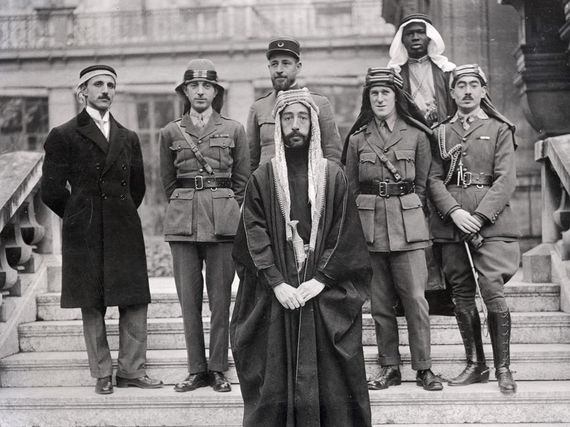

Prince Feisal and the Arab delegation at the Versailles Peace Conference. T. E. Lawrence is on his immediate right.

Prince Feisal and the Arab delegation at the Versailles Peace Conference. T. E. Lawrence is on his immediate right.

It would be incorrect to say that the current constellation of nations in the Middle East, or their national frontiers, was solely the result of the Sykes-Picot Agreement. The agreement, however, did represent the beginning of the direct assertion of European control over the Middle East and its division into national entities whose borders did not correspond to prevailing cultural, ethnic or religious divides. In that sense the modern Middle East, and all of the conflicts created by the superimposition of those ethnic, religious and cultural schisms on the current patchwork of national boundaries, is the direct and still enduring legacy of Sykes-Picot.

What began as a grab for oil in the waning days of the Ottoman Empire has reverberated over the decades since, and a century later is still shaping the dynamic of contemporary Middle East politics.