This past Tuesday, voters in Oregon, Alaska, and Washington, D.C., passed ballot measures to legalize marijuana, continuing a trend that began in 2012 when Colorado and Washington approved similar referenda. But what may seem like a surprisingly fast turn toward legalization has actually been a long, slow movement against pot's prohibition -- one that began in the early 1960s, peaked in the late '70s, and then failed to secure a single major victory again until the late '90s.

Possession of marijuana was a crime in every American state in the 1960s. A first conviction for minor possession could result in up to a year in prison in most states, while a second conviction could earn up to 20 years in places like Arizona and California. By mid-decade, surveys indicated that just 5 percent of American adults had ever smoked weed. Yet in 1964, the poets Allen Ginsberg and, later, Fugs member Ed Sanders founded LeMar (Legalize Marijuana), a group of pro-pot activists based on New York City's Lower East Side. LeMar staged tiny protests with just dozens of people, including one where Ginsberg, covered with snow, famously carried a placard reading "Pot Is Fun."

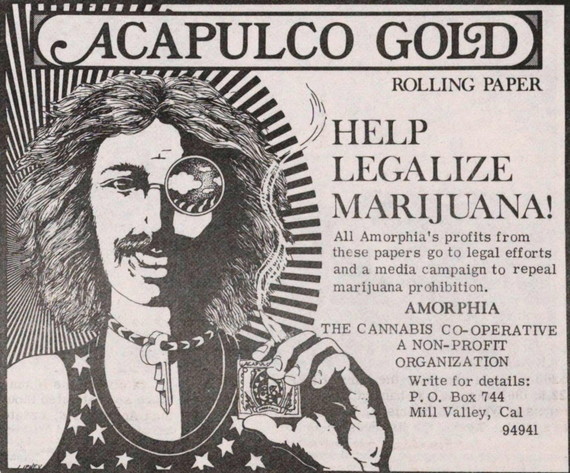

The marijuana-rights movement remained inconsequential, however, until LeMar merged with a California-based legalization group called Amorphia in 1971. Unlike LeMar, Amorphia had a promising fundraising scheme: It would produce its own brand of rolling papers, "Acapulco Gold," and sell them at about three times the going market rate. As Amorphia's newsletter announced to readers, anyone could "become an 'acapulco gold' sales representative ... [by] going around to head shops, bookstores, hip boutiques, and anyplace else that sells cigarette rolling papers in your area, and making sure they sell 'acapulco gold' papers." With the rolling-paper profits, Amorphia could then "fund an all-out media assault on Middle Amerika for legalization of marijuana (and perhaps other drug law reform)."

Amorphia achieved its first tangible success in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where two of the group's national chairs, the countercultural and activist supercouple John and Leni Sinclair, lived. In the late '60s, John had risen to prominence as manager of the proto-punk band MC5, and as founder of the White Panther Party, a white left-wing group that endorsed the Black Panthers' Ten Point Program while promoting their "own program of rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets." In 1969, however, Sinclair was convicted for marijuana possession and sentenced to 10 years in prison. In response, Michigan activists launched an international "Free John Sinclair" movement that culminated in a benefit concert headlined by John Lennon. After serving two years, Sinclair was released early in 1971.

That year, a circle of activists around the Sinclairs launched the Human Rights Party (HRP), a new political party that aimed to push local politics in Ann Arbor further to the left. The HRP sought to repeal all laws against homosexuality, to end American military involvement abroad, and to decriminalize marijuana. Two HRP candidates were elected to Ann Arbor's City Council in April 1972. The very next month they persuaded enough of their fellow council members to pass an ordinance making Ann Arbor the first municipality in the U.S. to make marijuana possession a civil offense, not a crime.

Amorphia felt it could most effectively reshape marijuana laws by funding campaigns for decriminalization on the state level. That fall, the organization donated tens of thousands of dollars to decriminalization referendum efforts in Oregon and in California, with roughly a third of funds coming from rolling-paper proceeds. Both propositions still failed despite these efforts. In California, only one in three voters favored decriminalization. In Oregon, however, the state formed a legislative committee in the following months that studied and ultimately recommended lifting criminal penalties for pot. The following year, in 1973, Oregon's legislature passed a law making it the very first state to decriminalize marijuana.

In 1974, Amorphia merged with the much better-funded National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), which was incidentally bankrolled by Hugh Hefner's philanthropic Playboy Foundation. NORML would play a leading role in securing marijuana decriminalization in 10 more states -- California, New York, Maine, Alaska, Colorado, North Carolina, Mississippi, Ohio, Minnesota, and Nebraska -- between 1973 and 1978. President Jimmy Carter even gestured toward decriminalization early in his term, stating that he hoped to "discourage the use of marijuana ... [without] defining the smoker as criminal." By the late 1970s, many people believed that national marijuana reform was on the horizon.

Decriminalization's advocates, however, had failed to recognize the strength of the backlash against marijuana's growing social and legal acceptance. Newly founded parents' groups like National Families in Action successfully lobbied legislators and influenced voters to stop passing decriminalization, and they also swayed President Carter away from drug policy reform. In 1981, advocates of harsh drug laws gained an even greater ally in the White House when Ronald Reagan took office. That decade, of course, saw the rise of the War on Drugs and an outpouring of harsh state and federal laws aimed at the possession of a variety of illegal substances.

For almost 20 years, the marijuana-rights movement did not secure a single significant victory. Finally, in 1996, California voters made their state the first in the country to legalize medical marijuana. New legalization groups emerged around this time, too, with the founding of the Marijuana Policy Project in 1995 and the Drug Policy Alliance in 2000. In 2008, Massachusetts voters approved decriminalization -- the first state to do so since 1978. Then, in 2012, Colorado and Washington became the very first states to vote to fully legalize recreational marijuana use by adults.

Thirty years may seem like an awfully long time for a movement to go without a major victory. But just as historians have written of a "long civil rights movement" that began at least as early as the 1930s before flourishing in the '50s and '60s, the marijuana-rights movement appears to have quickly gained traction in the last two years -- but actually builds on decades of legal battles and organizing.

The days of selling rolling papers to shape drug policy may be over, but businesses still play a major role in the marijuana-rights movement. Now they're much more organized (and buttoned-down), and they've even formed their own trade group, the National Cannabis Industry Association, as they strive for a new respectability in the eyes of voters and lawmakers. Yet while the legalization movement is currently enjoying unprecedented momentum, the setbacks and backlash that it and other social movements have faced since the 1970s suggest that continued victories are far from guaranteed.