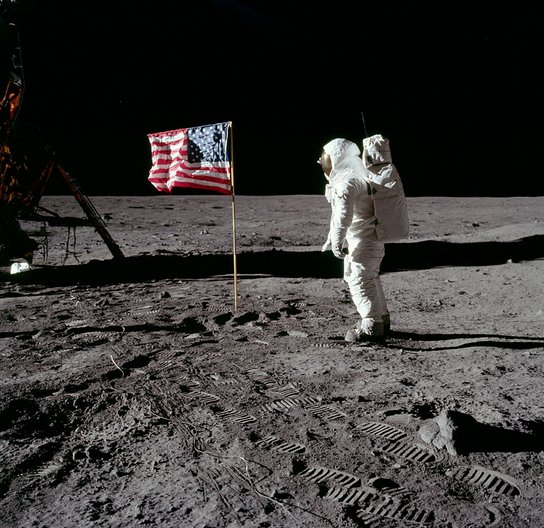

As an American-made robot slowly wheels itself across a Martian crater, a titan of U.S. space exploration is laid to rest. An invisible torch of far-more-than-Olympic significance has been passed from Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong to the scientists and astronauts of the twenty-first century. Mr. Armstrong was the first member of our species -- indeed, the first living creature from our planet -- to set foot on another celestial body. Billions of humans, and an unfathomable number of organisms, were born, reproduced, and returned to our soil before something of our realm possessed the evolutionary ability to unshackle itself from the chains of gravity and oxygen to plant their feet on alien rock. In the entire history of our planet, there is perhaps nothing that has equaled such an extraordinary achievement. When the Eagle finally landed, in the paraphrased words of Alan Moore's Watchmen, "The superman existed, and he was American."

Photo by Neil Armstrong, NASA

Mr. Armstrong became a legend in another era -- when two superpowers were locked in a war for supremacy across domains military, athletic, artistic, ideological, and scientific. Children dreamed of summers spent not in front of video game consoles but at space camp, and an individual's genius was not defined by the percentile of their standardized test score, but by their profession -- a profession--that of the rocket scientist. These were the men and women of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, better known as NASA, and they were irrefutably some of the most brilliant, resourceful, creative, motivated and well-educated human beings in the history of our planet.

The Eagle's landing itself was the result of thousands of scientists and support staff, and its achievement was global. Mr. Armstrong's infamous turn of phrase appropriately described NASA's feat as a species-level -- not simply a national -- leap in scientific progress, and one that was built on the discoveries and research of many before him.

Critically, the Apollo 11 mission succeeded because U.S. citizens, prodded famously by President John F. Kennedy, dreamed it, funded it, and willed it to achievement. President Kennedy understood that remarkable achievements require relentless commitment, persuasively arguing on May 25, 1961 -- less than three years after NASA's official creation -- the following:

"I believe we possess all the resources and talents necessary. But the facts of the matter are that we have never made the national decisions or marshalled the national resources required for such leadership. We have never specified long-range goals on an urgent time schedule, or managed our resources and our time so as to insure their fulfillment."

And so President Kennedy, backed by his Congress, marshalled the necessary resources, presented an urgent timetable with specific long-range goals (to put an astronaut on the moon by the end of the 1960s), and invested his trust in competent public administrators who would manage time and U.S. resources to insure the goal's fulfillment. Still, it is easy to speak of the novelty of space exploration without a more nuanced analysis of its costs and benefits. After all, who is to say what the same brainpower and resources would have accomplished if devoted to other endeavors?

Freakonomics, the popular blog of the Levitt and Dubner novel's namesake, points out five commonly raised benefits of U.S. space exploration, paraphrased as follows: 1) it has a high R.O.I., historically yielding an eightfold investment return for each dollar invested; 2) it furthers the eventual establishment of an extraterrestrial colony as a hedge against an Earth-based human extinction event (an exclusive benefit of manned space exploration); 3) it presents a venue for peacefully gaining diplomatic "soft power" and international respect; 4) it builds national prestige and patriotism, and; 5) it offers humanity insights into our most fundamental questions surrounding the nature and existence of life.

I am particularly gripped by this last point. As it was put by Apollo 16 astronaut (and fellow moonwalker) Charlie Duke in a 2009 interview with the Austin Statesman:

"The millions and billions who looked at the photos we took: I think it's probably the birth of the modern environmental movement. The loneliness of Earth, suspended in the blackness of space..."

In the same vein, Curiosity's photographs of the barren Gale crater -- bland though the images might appear to some -- are again reminding us of the rarity and significance of life on our planet. For all of our world's searching, we have yet found no examples of a similar benign prevalence, let alone diversity, of life, ocean and atmosphere. The discovery of past, current or potential future life on Mars would have more to teach us. If microscopic organisms exist and have existed for eons, what might that say about why we evolved while they did not?

Partial answers to questions such as these await the human race on Mars. President Barack Obama deserves credit for his administration's support and execution of the recent landmark Curiosity Mars rover landing, as well as for his suggesting a timeline (the mid-to-late 2030s) under which "he believes" we can land humans on Mars. The president has also advocated for specific intermediate steps such as first landing astronauts on an asteroid, and reaffirmed his administration's support of manned space exploration in response to a Reddit user's query.

Still, in contrast to President Kennedy, who explicitly committed the U.S. to achieving a goal within or shortly after his hypothetical second presidency, President Obama's specific promises for manned space exploration appear more cautious. Moreover, NASA spending, though up noticeably over the Bush era, remains low by historical standards at $17.8 billion -- 0.5 percent of the 2012 federal budget, or about one-ninth of the 4.3 percent share it held at its peak in 1965.

Ultimately, if the U.S. seeks to send a manned space mission to Mars or reach similar such milestones by the end of the 2020s -- or sooner -- it need provide no more than it did in the 1960s: funding, political will, and presidential accountability. For the near-term, admittedly unlikely until after the November election, a NASA-managed manned space program would need to transcend partisan talking points and emerge as a national priority. Specific intermediate goals would need to be set. Over the long-term, the U.S. would need to finally heed the cacophony of voices still shouting their tired call for the same investments: more support for STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education, more federal research grants, and a well-resourced federal space strategy.

Aspects of the first human mission to Mars will undoubtedly be different from the Apollo 11 moon landing. It will see more international collaboration, greater sharing of research findings, a heavier reliance on public-private partnerships, and a more decentralized supply chain. But other aspects of the mission will be unchanged -- it will still be the product of brilliant minds overcoming unprecedented scientific obstacles through trial and error, it will once more produce innumerable scientific breakthroughs, and it will again bring our world closer together by broadening our understanding of human life.

In the words of Arthur Russell, "This is how we walk on the moon." If we choose, it is also how we will walk on Mars.

This post was originally authored for The Wagner Review