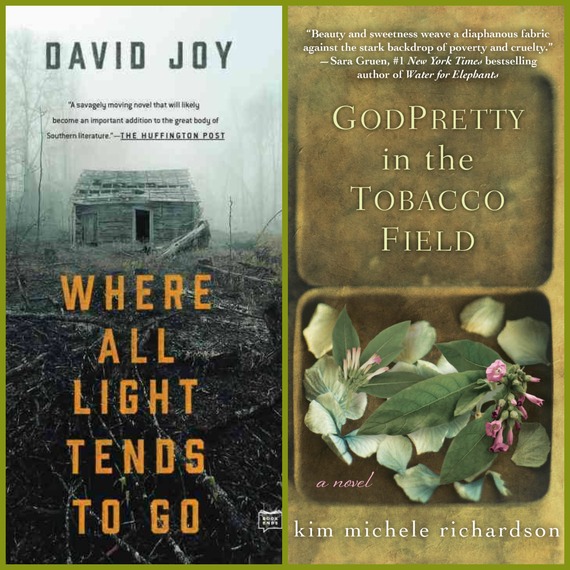

With the recent release of my book, GodPretty in the Tobacco Field, a novel that is set in mountainous eastern Kentucky, David Joy's powerful words resonated. They are an accurate and honest portrayal of why we write what we write, and why we must continue to write human stories that arise from our cornerstones. In one of my novels, Liar's Bench, I say a good cornerstone is the strength of any town, tale, or courtship just as sure as a liar's bench's weathered planks of oak and wrought-iron arms and legs cradling it are the support for its tale spinners and sinners. And, Joy, has a damn good cornerstone.

Today's essay, and two photos are courtesy of, and provided by my guest, David Joy. David is the author of the Edgar nominated novel Where All Light Tends To Go, as well as the novel The Weight Of This World, forthcoming from Putnam Books in early 2017. He lives in Webster, North Carolina.

When I sit down to begin a story, the canvas isn't blank in that there is already a place. There are already mountains and streams and buildings and roads, so that when a character finally arises, that character claws himself from the ground. Because he emerges from that place, he already has a name and an accent and mannerisms that are tied directly to the dirt from which he rose. That place for me is Jackson County, North Carolina and it is because that's the only place I know.

At the same time, I don't write books about Jackson County. Nor do I write books about Appalachia. I write stories about desperation. A fellow writer and friend, Brian Panowich, says I write love stories, and while I don't necessarily know whether that's true, I know it's a lot closer to the truth than to entertain that my stories are snapshots of a region. I write tragedy. I write the types of stories that I like to read, stories where any hint of privilege is stripped away so that all we are left with is the bitter humanity of it, stories about lives pinballing between extremes because there is nothing outside of sheer survival. Within those extremes, there is gut-busting laughter and there is heart-wrenching sadness, there is murderous anger and there is lay-down-my life love. That, for me, is the human condition.

We even have shoes

Yet, because of where my stories are set, I have people all the time, particularly people from outside this region, who ask how my work represents Appalachia. They ask whether the drugs and the violence that I write about are the cold reality of the place where I live, to which I always respond, "No more than right here." I once had some ritzy media escort wheeling me around in a Mercedes through some noisy city who asked what people where I'm from thought of my work, before stuttering, "Or can they read?" If it'd been a man, I might have hit him, but it wasn't and so I ate it, let that feeling roil around in the pit of my stomach for a moment, then responded simply, "Yes, we can read," then lifted my feet from her floorboard and shook my boots adding, "We even have shoes."

If it were up to me I would never leave Jackson County from now until the day I die. That may sound like an exaggeration, but it is not. I mean it. I mean it down to my very core. I'd be happy to stay right here within these 500 square miles from this breath forward. And more than that, I can tell you where I want them to bury my body. I want them to put me in the ground above Hamburg Baptist Church on that hill that's blanketed in phlox every spring, that hill that's so steep the flowers blow off of graves and gather in the ditch along the road that curves around Lake Glenville, that same hill where one of my best friends is buried. Put me in the ground beside of him. I'll be fine there.

I can give you a singular image of Jackson County's landscape. Our mountains are steep and almost every road follows water. We split the highest mountain on the Blue Ridge Parkway, Richland Balsam, which is also one of the twenty highest summits in the entire Appalachian chain, with neighboring Haywood County. We're home to the headwaters of four rivers: the Tuckaseigee, Whitewater, Horsepasture, and the Chattooga--that being the same Chattooga that Burt Reynolds paddled in Deliverance, but higher, up where that river starts as a creek, not down in the hot country running the Georgia/South Carolina border. In summer, the place is eaten with green, so much of it that that one of my mentors who came to these mountains from the desert said that she felt strangled by it. In winter, the trees are stripped down to their gray bones and in that nakedness you can see the contours of the mountains, the hollers and coves smoothed and weathered over the past 480 million years. There's some farmland along the river bottoms, but not near as much as say Haywood County to our east or Macon County to our west. The land here is too steep for the most part, a place better suited for black bear and deer, turkey and salamanders than people.

Drawing a singular image of our people, that's where things get difficult, or, rather, impossible. I can take you to someone whose ancestors were some of the first to settle here, people with names rooted to this place, names like Hooper and Woodring and Broom and McCall and Dillard and Rice and Messer and Mathis and Farmer and Coward and on and on till the cows come home. I can introduce you to people who still run bear with walker hounds and Plotts, people with wild ramp patches they hold in secrecy as if those onions were as valuable as ginseng. I can take you to front porches where people still gather on Sunday afternoons to pick stringed instruments and sing old ballads and hymns they've memorized like recipes. At the same time, I've sat in a bar in town and listened to a reggae band one night then turned around and heard world-renowned jazz guitarist Freddie Bryant grace the same tiny room the very next. Just a couple weeks back, I went and listened to a Pulitzer winner read from his work on a Thursday then went to watch "Midget Wrestling Warriors" beat the ever-loving hell out of one another in a high school gymnasium two nights later. There are hard working people and there are deadbeats. There are god-fearing people and the godless. There are outlaws and lawmen just as there are millionaires hitting golf balls on Tom Fazio designed courses just over the ridgeline from people surviving off of mayonnaise sandwiches. All of this is true. All of this is within Jackson County. Come here and I will show it to you.

Spend enough time here, keep your eyes and ears open and your mouth closed, and you may come to know this place. Know this place and you will know a part of Appalachia. But you will not know Appalachia as a whole any more than I do.

This is a region that stretches from the hill country of Mississippi to New York, an area covering 205,000 square miles across 420 counties in 13 states. I know people from Kentucky who will fight you for not pronouncing Appalachia the right way. "App-uh-latch-uh," they'll tell you. But I also know a woman born and raised in McKean County, Pennsylvania, a county just as Appalachian as Jackson, who will tell you her people say Appa-lay-sha, that her people don't dig ramps but they do dig leeks. Jackson County, North Carolina is not the coalfields of Kentucky or West Virginia. Coal isn't destroying our mountaintops; ours are threatened by development. What passes for mountains in the tip of Alabama would feel flat as a hoecake to someone who'd never been off the Balsams. Trying to unify this region under a singular paradigm is like trying to calculate string theory on an abacus. It's an absurdity. I've lived her most of my life and I can't.

There are hard working people and there are deadbeats. There are god-fearing people and the godless. There are outlaws and lawmen, just as there are millionaires hitting golf balls on Tom Fazio-designed courses just over the ridgeline from people surviving off of mayonnaise sandwiches.

As writers, we often stand painting a wall gray while people behind scream, "I love that it's black," or, "I hate that it's white." So often readers just don't seem to get it. Recently a fan from Denmark contacted me to ask about Appalachia following an article that ran in a Danish newspaper, Berlingske, a daily with a circulation of around 100,000. The title of the May 5, 2016 article was "Helt derude, hvor de hvide, fede og fattige bor," or what loosely translates to, "Way Out Where the White, Fat and Poor Live." In it, the author, Poul Hoi, used the recent Rhoden family massacre in Ohio and the novels of Daniel Woodrell and Donald Ray Pollock to argue that Appalachia is, "a heroless, malnourished, and uneducated America, where all of the goodness and normality has been sucked out to leave a tribe of murderous weirdos with rotten teeth." The bottom line is that someone who reads Daniel Woodrell and asks about Missouri (Missouri and its Ozarks being a long way from Appalachia, though there are plenty of similarities in our people), or who reads Donald Ray Pollock and asks how that book captures the Ohioan experience, is asking the wrong questions.

These aren't books about the South or about Appalachia. These are books about desperate people who have been backed into a corner and are left with no other option than to fight for their very survival. These are stories that, as Rick Bragg once put it, are "about living and dying and that fragile, shivering place in between." That's where the power of writers like Woodrell and Pollock and McCarthy and Larry Brown and William Gay and Ron Rash and Harry Crews has always lain, and that's not an Appalachian story or a Southern story.

That's a human story, one that could've just as easily been set in New York City. This is what Eudora Welty meant when she wrote, "One place understood helps us understand all places better." Violence and drugs are certainly present in Appalachia, just as violence and drugs are present in every place I've ever been, but the reality is that it happens at a much less alarming rate in this region than it does in a place like Chicago where as of May 17 there had been 1,283 shooting victims since the start of the year, a year that wasn't halfway through. These are stories about poverty and so if you want to have a conversation and you want to ask questions about what these books say about American culture, that's one place to start.

So why are these the stories that we read time and time again out of Appalachia and the South? I think that boils down to what stories are valued by the consumer. The reason dark, violent stories are popular is the same reason newspapers as far away as Denmark are covering the recent Rhoden family massacre in rural Piketon, Ohio. As a society, we're fascinated by violence. We eat up the sensationalism that the media feeds us day in and day out with a spoon. And this isn't just an American phenomenon. With wide eyes and imaginations running wild, we live for these types of stories, and, for me, that says much more about human nature than it ever could about a place.

I write the types of stories I write because it's what interests me, but even as I'm doing it I can recognize the danger. I can feel the tightrope beneath me. I told my editor recently that my biggest fear, what scares me to death, is that if readers don't get it, if I fail, then all I've done is perpetuated the very stereotype people outside this region have of me. It's one of the reasons I draw criticism from fellow Appalachian writers. But I think an artist has to work fearlessly to create anything that matters, so I put my head down and work. I write about poverty and drugs and violence not because its indicative of the place and region from where I come, but because those have always been the types of stories that interest me most. It's because I think a film like Ebbe Roe Smith's Falling Down or Ernest R. Dickerson and Gerard Brown's Juice say a lot more about society than any romance comedy. It's because I think writers like Larry Brown and Daniel Woodrell and Ron Rash illuminate the deepest grooves of the human condition more than any other writers I've ever read.

What is at stake when a reader takes a novel, particularly a noir or a piece of literary crime fiction, as is often the case, and believes the story wholly represents a region and a people is the same perpetuation of every other stereotype. It's listening to the rapper 50 Cent's Get Rich Or Die Trying and thinking that you understand the African American experience. It's watching a few episodes of Will and Grace and believing you know what it's like to be homosexual. It's staring blankly as a group of men fly airplanes into towers or walk into the crowded streets of Paris and open fire with automatic weapons and thinking they represent the entire Islamic faith. It's dangerous and it's disheartening. Misinformation and fear is what perpetuates hate.

So if you want to know what it's like in Appalachia read broadly. Read novelists like Silas House and Lee Smith. Read Robert Gipe's Trampoline and Crystal Wilkinson's The Birds of Opulence. Read Jeremy Jones memoir Bearwallow: A Personal History of A Mountain Homeland, who, by the way, does play the banjo, but who has a full head of teeth and an absolutely wonderful smile. If you want to know about the South read writers like Jill McCorkle and George Singleton. Read Rick Bragg's All Over But The Shoutin'. Read poetry. For God's sake read poetry! Read Wendell Berry and Maurice Manning and Jane Hicks and Darnell Arnoult and Denton Loving and Rebecca Gayle Howell and Frank X Walker, Ron Houchin, Ray McManus, Tim Peeler. But don't think of the people you meet in these books as Appalachian or Southern. To regionalize is so often to marginalize. Instead, see the humanity and question that rather than where they come from. Over and over, we all keep looking for differences. But now more than ever, we need to start seeing our similarities.

-David Joy, guest contributor