The word doesn't mean what many seem to think.

In response to my piece this summer about the hubris among some sustainable design leaders ("A Darker Shade of Green"), a reader Tweeted that "no one outside of field knows what you mean by sustainable" [sic]. Of course, sustainability transcends the fields of architecture and design, but it's true that the word can be confusing--in large part because it doesn't mean what many seem to think it does.

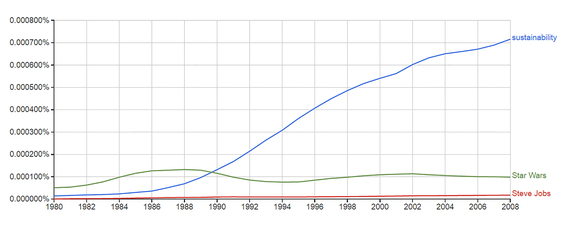

First, the term is extremely familiar. Googling "sustainability" gets more hits than "Grand Canyon" or "Gandhi." Searching for the term in the Google Ngram Viewer, which Time magazine calls "the closest thing we have to a record of what the world has cared about over the past few centuries," shows that as of 2008, the latest year available, the word appeared in literature seven times more often than "Star Wars" and a dozen times more often than "Steve Jobs," a man so influential back then that Fortune magazine wondered if he was more popular than Jesus. (He wasn't, it concluded.)

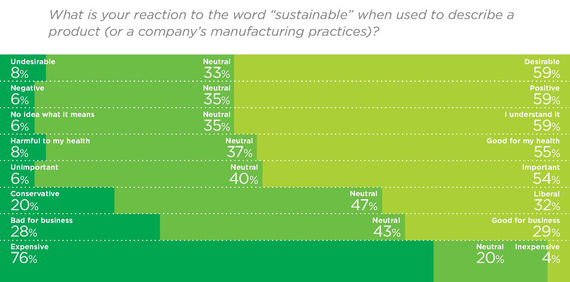

While the word is well known, its definition is widely perceived to be elusive. "What the hell does 'sustainable' even mean?" asked Salon, just two years ago. "The term 'sustainable' is utterly meaningless," author and local-food advocate Douglas Gayeton told Salon. "It's meaningless because corporate interests latched onto the word because they felt that it resonated with people." Last year, Casey Dunning, then a senior policy analyst at the Center for Global Development, told NPR, "Ask any given analyst and you would get a different definition on any given day." A 2015 survey found that 62% of consumers believe in climate change but only 54% feel the word "sustainable" conveys something important. Only 59% claim to understand it at all, and 76% consider it "expensive." In the absence of clear definitions, words risk losing meaning altogether or taking on negative associations.

Among those who do claim to understand the term, many define it very narrowly. Popular and academic sources alike explain sustainability in purely ecological terms: "the property of biological systems to remain diverse and productive indefinitely." In other words, sustainability is synonymous with environmental conservation--"saving the planet."

But sustainability has always meant much more than this.

When Kira Gould and I conducted research for our book, Women in Green: Voices of Sustainable Design (2007), we wanted to understand the origins of the concept. The earliest instance we found of the term with its current connotations was in The Limits to Growth (1972), a study of the earth's carrying capacity in relation to the population explosion (when global population was half what it is now): "It is possible to alter these growth trends and to establish a condition of ecological and economic stability that is sustainable far into the future," declared Donella Meadows and her co-authors. "The state of global equilibrium could be designed so that the basic material needs of each person on earth are satisfied and each person has an equal opportunity to realize his individual human potential."

This predates by 15 years the most frequently cited definition of sustainability, included in Our Common Future, the 1987 UN-commissioned study known as the Brundtland Report: "Humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

For nearly half a century, the concept of sustainability has focused first on human needs and potential, which depend on and significantly impact natural systems. Our fate is bound to the fate of the earth.

In 1994, John Elkington coined the term "triple bottom line" to clarify sustainability as the integration of social, economic, and environmental value. I can think of nothing of value that doesn't fall into one or more of these categories. Family, friendship, love--these are social values. In other words, sustainability encompasses literally everything. Yet, one of the most common complaints I hear from my peers and colleagues is, "My clients don't care about sustainability." If it includes everything, then you're saying your clients don't care about anything. No one is that apathetic.

Peggy Liu, whom Time magazine has called a "Hero of the Environment," insists that "sustainability needs to move from gloom to hope." But if the aim of sustainability is fully realizing human potential, as Meadows claimed four decades ago, what could be more hopeful? Its appeal would seem universal and timeless, but many declare, as Liu does, that "sustainability is dead." Similar obituaries are increasingly plentiful, and that phrase appears online 30 thousand times.

How could the idea of humanity flourishing forever suddenly go out of fashion? Trend watchers outline three phases of the fashion cycle--emergence, emulation, and saturation. As the Google graph shows, sustainability's tipping point was circa 1987, after the Brundtland Report appeared. The idea had been brewing for 15 years and suddenly boiled over. After 1990, the concept became more and more popular, which new organizations, such as the US Green Building Council, appearing, along with increased media attention and consumer awareness.

Over the past decade, however, the word has provoked irritation among many. Possibly the earliest declaration that "sustainability is dead" was by Alan AtKisson in 2006, and in 2010 Advertising Age included "sustainable" in its "jargoniest jargon" list. Oversaturation had begun to set in, and with the recession many organizations, communities, and companies slowed their efforts to embrace sustainability. A 2013 survey of CEOs by Accenture and UN Global Impact showed that a majority felt a lack of financial resources was the single largest barrier. "We are concentrating on strategies for today," said one executive, "not strategies for tomorrow."

Gayeton told Salon in 2014, "I think the climate movement has had a tremendous difficulty in the past 10 years because most people--most general people--have term fatigue. They have climate fatigue because of terms like 'carbon debt': They didn't really get it the first time, and they didn't know what it meant the 20th time, so they just sort of tuned out." He launched The Lexicon of Sustainability to demonstrate "a simple premise": "people will live more sustainably if they understand the most basic terms and principles that will define the next economy."

Sustainability isn't a trend, it's an ethic, and it can never become unfashionable, even if its language does. The challenge for those of us who champion the idea is to continue to find new ways--and new words--to inspire change. "In the end," observed Baba Dioum in 1968, "we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught."