I can't believe we're having this conversation, but let's try.

The events of 50 years ago which culminated at the Edmund Pettus Bridge were dramatically recreated in the film Selma. The very same issues are now being played out in real time on our television sets in the events transpiring over the past several days on the streets of Baltimore. Both serve as reminders of the work yet to be done to achieve a more equitable and just society.

Hillary Clinton acknowledged this reality, saying, "We have to come to terms with some hard truths about race and justice in America" -- to which we would add, "Why stop there? What about the schooling of children of color from poverty backgrounds? Don't we also need to come to terms with some hard truths about race and education as well?"

Who, however, will depict their plight? Who will speak for the children?

What better voice than the children themselves?

Italy

"Dear Miss,

You don't remember me or my name. You have flunked so many of us. On the other hand I have often had thoughts about you, and the other teachers, and about the institution which you call 'school' and about the kids that you flunk. You flunk us right out into the fields and factories and there you forget us."

Thus began Letter to a Teacher (Lettera a una professoressa) by the Schoolboys of Barbiana, a book in the form of a letter addressed to a composite teacher, by eight students speaking with a single voice.

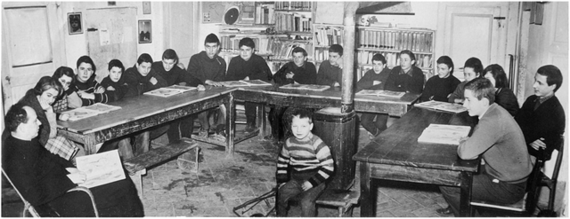

All were students in a small school, located in a remote Italian village of about twenty farmhouses in the hills of the Mugello region, in Tuscany.

The school was the brainchild of Lorenzo Milani (1923-1967), a progressive educator, journalist and priest who created it as an alternative educational setting for poor children who had been pushed out from traditional schooling. Born into poor families, these schoolboys had been told by former teachers that their futures were limited. Most had either flunked out of school or were bitterly discouraged with the way they were taught.

It began with 10 peasant students, schoolboys, 11 to 13 years old and a rigorous schedule of eight hours of work per day, six to seven days a week and later grew to 20 students, with the older students teaching the younger ones.

The school was quite different than anything the children had previously experienced. Under Milani's guidance, they learned how to write and think for themselves. They also learned to overcome their social-class limitations. The school respected the boys as learners and honored their backgrounds.

It s curriculum included the analysis and discussion of the children's own lives, which included a year-long project (coordinated by Milani) about their experiences in the school system, a two-tiered authoritarian structure based on business-like management models which emphasized testing and grades, was cluttered with irrelevant curricula, placed an emphasis on rote learning and grill and drill, and had as its central mission, the sorting and classification of children by class for a future dead-end role in society.

The letter is an eloquent diatribe of the children's own experiences in the public schools and the favoritism and class-bias of the entire educational system. It is one of the most simple but most forceful pieces of writing of the 20th century on school and social class and a powerful, indictment of how schools are complicit in perpetuating social injustice.

Brazil

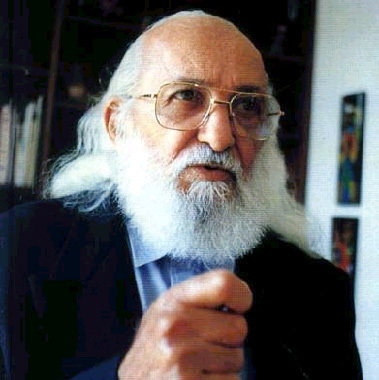

That very same year (1966), Paolo Freire's classic work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed was published. Freire had worked for years with the campesinos, "the shirtless ones," those laboring in the fields of Brazil in efforts to raise adult literacy.

His approach to schooling also began with his students, integrating the mainsprings of their lives; their fears, hopes, aspirations, and concerns as the point of departure and the subject matter, dictating both classroom practice and the politics of the school.

Rejecting the traditional banking approach--the staple of traditional education whereby inert material is simply deposited into the student's account-- he replaced it with a process that was mutual and dialogical, in which students continually questioned and took meaning from everything they learned.

In the process, they learned how to think democratically and to take control over their own education and their own life, emerging with an elevated personal, political and social consciousness, whereby they became the subjects, rather than objects, of the world.

This had implications on a much wider level as well. Education would be not apart from the world but a part of it. At its most effective, it would be transformative for both the learner and the society.

New Zealand

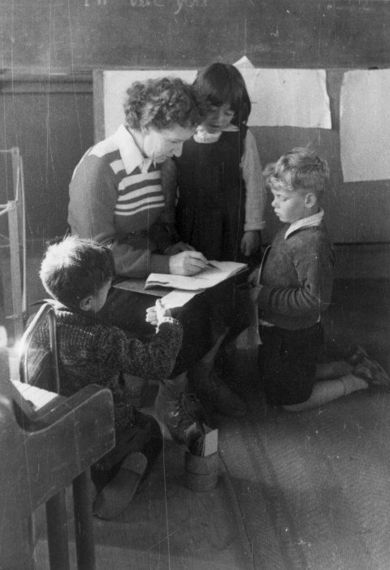

Four years later, Sylvia Ashton-Warner published her book, Teacher, recounting her experience teaching the Maori children of New Zealand.

Her approach towards introducing primitive children to the world of words was simple yet direct.

They (the words) must be made out of the stuff of the child itself. I reach a hand into the mind of the child, bring out a handful of the stuff I find there, and use that as our first working material... And in this dynamic material within the familiarity and security of it, the Maori finds that words have intense meaning to him, from which cannot help but arise a love of reading. For it's here, right in this first word, that the love of reading is born, and the longer his reading is organic the stronger it becomes, until by the time he arrives at the books of the new culture, he receives them as another joy rather than as labor. I know all this because I've done it.

The approach of Milani, Freire, and Ashton-Warner is far different than the philosophy which today dictates the education of urban kids (read poor black and brown children). Martin Haberman called it "The pedagogy of poverty."

Rather than facilitating student ownership of the educational content or treating them as partners in it, content is directive, tightly controlled and superimposed from above.

It has powerful and varied advocates: Those who fear minorities and the poor and have low expectations for them; those obsessed with control; and those who themselves have been brutalized and marginalized by the process; as well as business and reform-oriented leaders working from their narrow world view, believing it to be the only way of structuring reality,

Call it what you may, the approach at its heart is racism, masquerading as hope, working to perpetuate the current social and political reality.

Washington D.C.

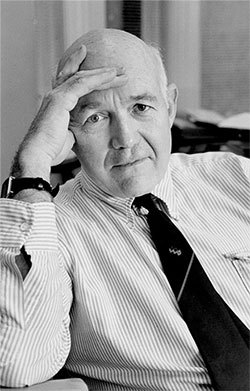

We are fast approaching the 50th anniversary, one of the single best-known pieces of social science research ever done on our schools. Named in deference to its senior author, sociologist, James Coleman, "The Coleman Report" is the second largest social science research project ever produced in this country's history--an effort deemed "impressive," even by today's standards. The study was produced under the authority of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The resulting report, "Equality in Educational Opportunity," was published in July 1966.

The central finding of the report was that what occurred in a child's home and in their neighborhood and though their interactions with peers were far greater determinants of academic success than anything schools might do. Few school-related "inputs" seemed to matter much in terms of overcoming the academic disparities which children brought with them. Only teachers' verbal ability seemed to be linked to higher student test scores and improving student achievement.

That's what people remember most about the report. What many took away from it was the notion that "schools don't matter," an argument which many politicians used in opposing further educational funding--an interpretation which was greatly oversimplified.

Virtually lost in its discussion was what the report found to be the next--most important determinant of academic achievement after family characteristics--a student's sense of control over his or her own destiny.

If the motivational problems of the poor is to a significant degree rooted in the conviction, resulting from the experience of a rigid or chaotic home and street life, that they cannot influence the relevant parts of their environment, surely the efforts of school to prevent their reflecting on, evaluating, and attempting to influence the environment of the school itself, could only further confirm their belief in the fruitlessness of making any effort toward self-mastery.

If the primary cause of lack of motivation among the poor is their feeling that they cannot control their own destiny - that feeling can only be reinforced by placing them in highly politicized and manipulative programs of compensatory education whose success is largely defined in terms of percentage of students gotten into "quality" colleges.

Oh yes, the report also noted that African-American students in schools with mostly white students had a greater sense of control. But forget about that. The goal of school integration has long since passed us by.

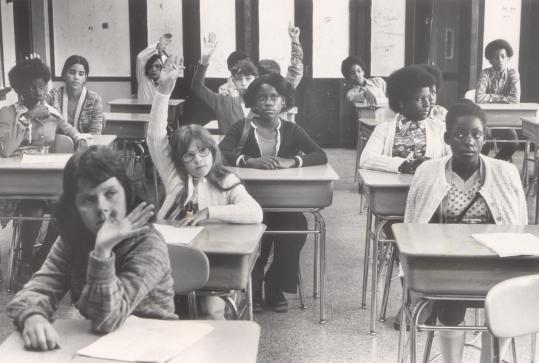

Baltimore

The Baltimore school system ranked second among the nation's 100 largest school districts in per pupil expenditures in fiscal year 2011, $15,483 per-pupil, second only to New York City's$19,770. As reported in the Baltimore Sun: Respondents asked to grade the Baltimore public schools, gave it the equivalent of a grade-point average of 1.45, about a D-plus.

How to address this disparity? Empowering the students might be a good place to start. Taking the lives of students seriously invariably leads to having to also take seriously the larger context in which schooling is played out. Empowering students goes hand in hand with empowering the community.

That is the challenge we face today.

Whoever is fond of the comfortable and fortunate stays out of politics, he does not want anything to change. To get to know the children of the poor, and to love politics, are one and the same thing. You cannot love human beings who are marked by unjust laws, and not work for other laws.

----The Children of Barbiana

Larry Paros is a former high-school math and social-studies teacher. He was at the forefront of educational reform in the 1960s and '70s, during which time he directed a unique project for talented underprivileged students at Yale and created and directed two urban experimental schools, cited by the U.S. Office of Education as "exemplary" and later replicated at more than 125 sites nationwide.