Posted by David Braun of National Geographic. This post originally appeared on National Geographic NewsWatch.

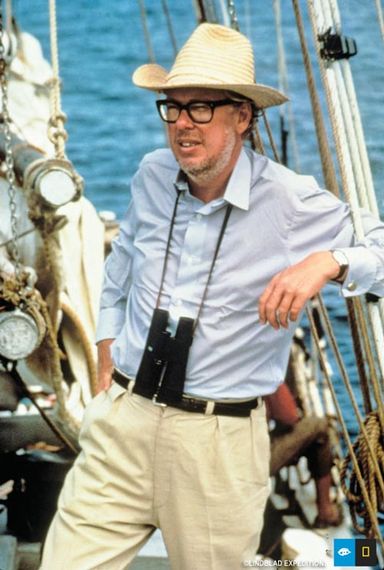

Ten years ago Lindblad Expeditions and the National Geographic Society joined forces to inspire, illuminate, and teach the world through expedition travel. The collaboration in exploration, research, technology, and conservation has provided extraordinary experiences to thousands of travelers, raised funds and awareness to address critical challenges to the environment, and inspired people to be better stewards of the planet. In this National Geographic-behind-the-scenes interview, Sven-Olof Lindblad, founder and president of Lindblad Expeditions, talks about the impetus behind the partnership, some of the accomplishments, and his thoughts of the future.

Lindblad and National Geographic have been in partnership for ten years. How did they come together?

It always struck me that National Geographic stood for the "world and all that's in it," and Lindblad took people to experience the world. So it made a lot of sense to me that we should partner with National Geographic.

Until that point, National Geographic had been a very significant part of my life, and my father's life, and not just because we accumulated magazines with a yellow border. If you go back to the 1960s and 1970s, before we had Google, the magazine was an extraordinary source of material for research, providing inspiration for places that we might want to go. That led us to want to develop relationships with National Geographic scientists, naturalists, writers, and photographers. Incidentally, the magazine still is all that, although, clearly, there are many new places to derive information.

National Geographic was this omnipotent force, if you will, in our developing expeditions travel, so the opportunity to have a more formal, concerted, and engaged involvement with the Society seemed to make a lot of sense.

So how does the partnership give effect to that aspiration? You take people "there," but you also participate in, and extend, National Geographic's mission programs, right?

There are a variety of components. Obviously, National Geographic has its National Geographic Expeditions travel program, so one of the components is that National Geographic Expeditions would focus entirely on our ships for its marine platform.

We created a joint conservation, exploration, and education fund, because both National Geographic and Lindblad Expeditions believe that there is an opportunity to find creative ways to engage travelers with some of the challenges to be dealt with in the world. So we have collaborated very closely on that. Currently, for example, our main focus on the National Geographic Explorer for the next five years will be to support National Geographic's Pristine Seas program, together with [marine ecologist and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence] Dr. Enric Sala.

Enric Sala is a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence actively engaged in exploration, research, and communications to advance ocean policy and conservation.

We collaborate considerably on getting interesting people aboard these various expeditions, to add value and inspiration for our guests, and that comes in the form of scientists, explorers, photographers, and any number of different experts within the National Geographic community to augment our own teams. We're trying to constantly find ways to use the assets of National Geographic and the assets of Lindblad to really focus on two things: Where we can add value to the guest experience, and how we can broaden the participation of people in caring about and participating in the solutions for the global challenges we all face.

Does the selection of destinations play into this vision?

Yes it does, obviously because we have a very close relationship with a pretty big brain trust. We reach out to this brain trust to look for where we should go, why, and what we would do there. That's an integral part of building our program. So when we are in a new area, whether it be Borneo, Indonesia, the South Pacific, the Indian Ocean, we're always looking for areas where National Geographic is doing some work.

We know pretty much that within National Geographic there's an expert or experts that can help us better understand the details of what we want to do. An example of this would be how we've been talking with [National Geographic Emerging Explorer] Andrea Marshall recently about the coast of Mozambique. Andrea is doing a lot of work with marine megafauna along the Mozambique coast. We will be going there in March/April 2015.

[The Marine Megafauna Foundation, which Marshall co-founded, conducts world-leading research from Mozambique's remote southern coastline, home to one of the largest identified manta ray populations. Watch Andrea Marshall give a National Geographic Live! lecture about her manta research. ]

We're also working with one of Enric Sala's expedition leaders to see if we can get permission to visit the Chagos Marine Reserve, which is off limits to visitors. We don't know yet whether we will or won't get permission, but if we do, that will be a tremendous coup for everyone involved.

We're collaborating with Enric's team to create an economic proposal for various governments that would help encourage those governments to be enthusiastic about the creation of marine protected areas.

There's a whole variety of areas where human capital comes into play as a result of our partnership with National Geographic.

Lindblad Expeditions has a hallmark for sustainability. What does that actually mean in your enterprise?

Sustainability is perhaps an over-used word these days. What we are constantly looking for is a clear, positive relationship between us as an enterprise, our guests, and the places that we visit. At the end of the day, the lens through which we look at the world is shaped like a triangle. We have the traveler on one point of the triangle, the destination on another point, and the enterprise on the third point. And the only way things are ultimately sustainable from a business perspective is if value flows in all directions.

What we are looking for are creative ways in which we as a company and our guests can contribute to some of the needs and challenges of the places we visit. So for example in the Galapagos Islands, where we have been engaged for a long, long time, there are issues like introduced species, patrolling the marine reserve, educational challenges, and artisanal development as alternative sources of income - and we have a pretty broad program that touches on a variety of opportunities to do something about these challenges.

We also try to leverage our relationship with other people to get matching funds and get them involved in some of these programs. As an example, the Helmsley Trust, which is an organization with which we collaborate very closely, is a partnership where we act in an advisory capacity for them in the areas that they're interested in.

We make an effort to make sure that our fish, for example, are sourced sustainably. We try to make sure that we are not buying fish that are overfished or are in any shape or form on a Threatened list.

So this idea of sustainability and engagement, trying to find creative solutions, is a deeply rooted component of the enterprise. We have someone that heads that up on a day-to-day basis, and coordinates and works with us, the board of the fund, and the local institutions, wherever it is that we travel.

Lindblad seems to have a special affinity with Svalbard. Why is that?

We've visited Svalbard for a long time, and of course Svalbard and all of the Arctic is an area where one of the primary conversations is climate, and how you can see the effects of climate change more dramatically in these northern territories than you can anywhere else in the world. So it's a perfect backdrop for having that conversation.

What we can see in Svalbard, in particular, is the significant diminishing of sea ice. And for a species like polar bears, we can see how their whole pattern of migrating within this system has changed dramatically as a consequence. So it becomes a valuable educational tool to make people realize that change is real, it is not a fantasy, and it is happening in accelerated ways in the Arctic. Svalbard is a great, great teacher as it relates to that.

National Geographic focuses on three core areas - inspiration, illumination, and teaching. What is your commitment, personally and in the enterprise, to educators? I know you have a program for teachers.

Yes, we have the Grosvenor Teacher Fellows program going since [former National Geographic President and Chairman] Gil Grosvenor had his 75th birthday in 2006, and we have been accelerating this program.

This year we will take 25 teachers on the National Geographic Explorer to the Arctic and Antarctic. Next year we hope to expand that to 50. The notion of getting teachers out where they can have a profound experience, like the one in Svalbard, and then helping develop tools so that they can leverage that experience in their classrooms and with fellow teachers, is a very good idea because it inspires them to become better teachers.

So we're very excited to bring this to scale. It's taken a while to work out the mechanics of how to do that, but now I think we will be very much on an accelerated path. Our goal is to take hundreds of teachers out in the years ahead.

There was a moment in the history of the Lindblad partnership with National Geographic when the two organizations, in collaboration with The Aspen Institute, took a ship full of thought-leaders, including some of the Elders, to the Arctic to exchange ideas and discuss what could be done to raise awareness of climate change. What was that about?

In 2008 we aggregated a group of political leaders, scientists, business leaders, and religious leaders, and brought them to the Arctic with the notion of having a conversation in a location that would create a backdrop of inspiration, to look at how the whole subject of climate change could be furthered across sectors.

Climate has business, security, health, economic, and other components. The strategy to combat the situation can't be resolved in isolation. You can't solve it politically in isolation, or with business in isolation. These components have to work in concert. So this was a representative and potent group from these various sectors. They had the chance to see the Arctic first-hand. They developed very strong bonds with one another, and they began to develop some empathy for what the political, scientific, and economic realities were.

Members of the 2008 Climate Action expedition explore the tundra in Hornsund, Svalbard, Arctic Norway.

I think it was a very successful endeavor. There was a vision of having a significant follow-up, but of course in September of that year we saw the beginnings of an economic collapse and everything to do with climate went completely off the radar for a while. [Read a statement released by the participants in the voyage: From the Arctic, A Statement of Hope & An Appeal For Action.]

Video: 2008 Arctic Expedition for Climate Action aboard the National Geographic Endeavour.

National Geographic leaders certainly came away a lot more thoughtful after that trip. The Society focused more intensively on Earth's lifelines, for example, and has given more attention to themes such as freshwater, sustainable energy, food, and healthy oceans. Were you aware of any other outcomes of that July 2008 gathering?

It's difficult to quantify. The whole idea of keeping that group connected and engaged became completely gutted by the economic collapse. But I do run into these people periodically, and there is no question that the experience affected their thinking. I wish I could know if someone like Larry Page made any moves within Google as a consequence of that experience. Did the CEO of Monsanto change anything inside his company as a consequence of that experience? What I do know from these people is that they were profoundly affected by the experience, and I cannot help but think that it resulted in some changed behavior.

Your father, adventure-travel pioneer Lars-Eric Lindblad, left you a legacy of thinking and acting in a certain way about the travel business. What is your commitment to his vision?

My father, when he started his enterprise in 1958, brought people to very remote places, many of which we take for granted now. If you imagine going to the Antarctic as lay travelers in the 1960s, that was a pretty extraordinary idea that some people thought was total madness. So he pretty much opened up the world. He was the first to bring people to the Arctic in an organized way, and he did the same for the Antarctic, the Galapagos, much of the Amazon, certain parts of Africa, Mongolia, Bhutan...the list goes on and on.

My father was always imbued with the idea that travel was an incredible opportunity to make people look at, and consequently think of, the world differently. It became apparent to me at a very young age that travel, where you combine extraordinary geography with really smart people, created a vibrant conversation about issues that mattered. Things would happen in a very profound way over time, because many of these travelers are people who influence the destiny of the world in one form or another.

That's turned out to be true, and I think that is unassailable.

So what we do now and intend to do going forward is just to apply more strategy to what fundamentally is a rock-solid idea that came out my father's experiences and his drive. We want to create a greater sense of urgency around some of these ideas, because in the 1960s and 1970s nobody was talking about issues like climate, nobody was talking about the notion that we might, within the next decades, have a completely unsustainable global fishery. So there was not that kind of urgency.

No one was talking about the fact that we might obliterate the wild populations of lions in our lifetime. So all of a sudden the main difference between the conversations that were taking place in the 1970s and the ones that are taking place now is really a factor of urgency. We've done too little for too long, and what we have done, and not done, is exasperating our relationship with natural systems.

We have the science and we have the knowledge, but not the political and social will to act strongly enough. So now a lot of these issues are getting to the point where they are very, very critical. Everywhere I look now, there are critical issues.

People often ask me if there were any seismic moments in my life, ones that had profound effects. One of the stories I refer to often was when I was living in East Africa in 1972, and just for fun I went out into a national park called Tsavo East, near where I was living, to see how many rhino I could find in a day. I found 59. But only seven years later I was in that same national park for a week and couldn't find one rhino. That was when it dawned on me that human beings have way too much power. This was the place that had the largest population of black rhino in Africa, and essentially we wiped them out within an extraordinarily short period.

I have a different experience, about the white rhino. When I was a boy I visited the Kruger Park in South Africa in the 1960s and it was difficult to spot a rhino because they had been poached almost out of existence. And then South Africa made a remarkable recovery effort, and even today in Kruger, which is now again losing a rhino a day to poachers, one can see many rhinos. It may be that ultimately we will lose the rhinos, but it does show that we were able to reverse the tide for a while, and that if we apply ourselves, nature can rebound quite strongly.

There is no question of that, and there are some regional success stories, but at the end of the day, the global trajectory is troubling. Take sharks, for example. You know that they have been hammered for some years already, and if you combine that with the growing middle class in China that has the resources and the desire to have shark-fin soup at weddings, a sudden explosion of consumers that can afford it, it's pretty much a death sentence for sharks. There are these patches of success, but by and large, global behavior is not indicating any overall success. Cultural shifts are necessary if we are to avert disaster.