(graphic by Davin McHenry)

A New York Supreme Court judge will decide whether the public has a right to see individual teacher ratings based on student test scores in the nation's largest school district, an indication that the days when 99 percent of teachers were rated "satisfactory" are over.

Arguments before the court will be held on November 24 and come at a time of intense national interest in finding better ways to judge the effectiveness of teachers. Regardless of what the court decides, the idea of holding teachers accountable for student performance seems here to stay.

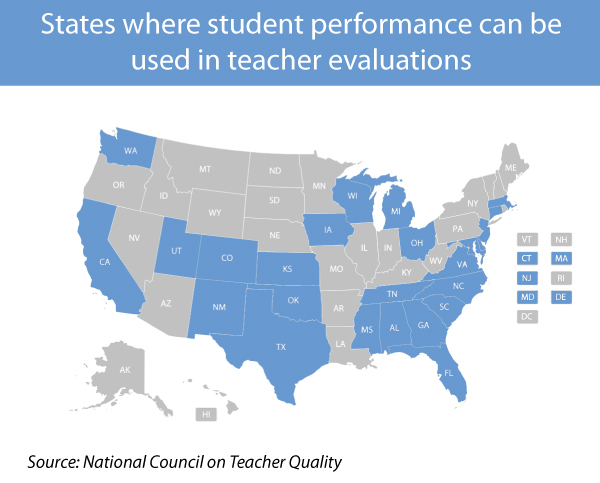

Nationally, many teacher evaluations already take into account how much students learn -- and school districts across the United States could soon be required to make similar disclosures of teacher ratings. The push comes after the Obama administration insisted that states competing for grants in its $4.3 billion Race to the Top program find ways to link student performance to teacher evaluations. Twenty-five states now have policies that permit this, and hundreds of school districts -- including Chicago, Denver and Washington, D.C. -- are using so-called value-added models to crunch the numbers.

"Value-added" ratings use complex statistical models to project a student's future gains based on his or her past performance. The idea is that good teachers add value by helping students progress further than expected, and bad teachers subtract value by slowing down their students.

New York City's Department of Education thinks the public has a right to view the ratings of the city's 12,000 public elementary and middle school math and English teachers, along with their names and schools. But the United Federation of Teachers filed suit to block the move on Thursday, calling the ratings unreliable and the methodology used to calculate them unproven. The city agreed not to release the names for now, pending next month's hearings.

Releasing teachers' names and ratings, the union's petition to the court notes, could irreparably damage the professional reputations of thousands of public school teachers. New York media organizations have sought the data in the wake of the precedent set by the Los Angeles Times, which this summer created a publicly accessible database of teacher ratings.

Natalie Ravitz, a spokeswoman for New York City Schools Chancellor Joel Klein, said the data is an indicator of a teacher's effectiveness, and that releasing the data was in the public interest. "Value-added data doesn't tell the whole story of a teacher," Ravitz said in a statement. "But when teachers consistently perform at the top or the bottom, year after year, that is surely important... these are public schools and public tax dollars."

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said he gives the city credit for sharing the information with teachers, so they can use it as a tool to improve. "I also think that parents and community members have the right to know how their districts, schools, principals and teachers are doing. It's up to local communities to set the context for these courageous conversations but silence is not an option," Duncan said.

Rob Weil, deputy director for educational issues at the American Federation of Teachers, disagrees, and said that while the union is looking for better ways of evaluating teachers, test scores are not enough. "We agree that there need to be better ways of evaluating teachers, but these scores are not a good measure. They are not fair, they are not adequate and they are not accurate," Weil said.

Dan Weisberg, general counsel of The New Teacher Project, a national nonprofit that has advocated for overhauling teacher evaluations to improve student learning, said there is new momentum for change. "Districts and unions also need to work together to provide parents with more and better information about teacher effectiveness -- if not individual ratings, then at least school-level statistics, as teachers are the most powerful school-based factor in student academic success or failure," he said.

Using value-added models to calculate teacher effectiveness wasn't possible on a wide scale until recently. In the 1990s, William L. Sanders, a statistician at the University of Tennessee, pioneered the technique with student test scores. The method -- as Sanders puts it -- is like measuring a child's height on a wall. It tracks a child's academic growth over the year, no matter how far ahead or behind the child was initially. Sanders discovered that teacher quality varied greatly in every school, and found that students assigned to good teachers for three consecutive years tended to make great strides. Those assigned to three poor ones in a row usually fell way behind.

Education historian and author Diane Ravitch has become a vocal critic of value-added measures, even though she once believed they could be used as one of multiple measures to evaluate teachers. She now believes they drown out every other measure, have a wide margin of error and should never be used at all. "Teachers will be mislabeled and stigmatized. Many factors that influence student scores will not be counted at all," Ravitch wrote on the Washington Post's "Answer Sheet" blog earlier this month.

Value-added models aren't perfect, as even their most ardent supporters concede. Oft-cited shortcomings range from doubts about fairness to broader concerns centered on teaching goals. And those who champion value-added measures caution against using them as the sole means of evaluating teachers. Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, a research and advocacy group in Washington, D.C., has called value-added the best teacher-evaluation method so far. But she also says it would be a "huge mistake" to rely on it alone, or even primarily.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, doesn't oppose the use of value-added data but wants to ensure evaluations are based on "classroom observations, self-evaluations, portfolios, appraisal of lesson plans, students' written work" as well.

"It's a valuable part of the conversation," said Timothy Daly, president of The New Teacher Project. "It puts what matters most -- student achievement -- front and center as the most important responsibility for a teacher."

Barbara Stewart contributed to this article.