The world's top-rated chess player Magnus Carlsen of Norway qualified from the Candidates tournament in London to challenge the reigning champion Vishy Anand of India in the world championship match in the fall of this year. Carlsen, 22, won in the English capital by a squeaker after a dramatic last round, played on April Fools' Day.

Before the last round, the Norwegian grandmaster shared first place with Vladimir Kramnik of Russia before the last round. Having a better tiebreak, Carlsen could qualify by matching Kramnik's result in the crucial last game. That night Carlsen had a terrible dream: he drew his last game and Vladimir Kramnik won, qualifying for the world championship match against Anand. The reality was even worse: Carlsen lost to Peter Svidler of Russia. But Kramnik lost, too. Although both players shared first place, Carlsen became the challenger for the world crown having won more games than the Russian.

The double-round robin Candidates tournament featured most of the world's best players.

Standing from the left: Teimour Radjabov, Magnus Carlsen, Alexander Grischuk, Levon Aronian,

Vassily Ivanchuk; Seated: Peter Svidler, Vladimir Kramnik, Boris Gelfand

Here is the final crosstable:

Two players were singled out to win the Candidates before the tournament began and the first half went as predicted: Carlsen and Levon Aronian of Armenia won three games each, drew the rest and took the lead. Nobody else crossed the 50 percent mark.

The two leaders were on track to repeat the score in the second half. Who would blink first? Aronian usually takes more risks, often pushing his luck. He tripped first, losing to Svidler. With five rounds to go, Carlsen was in the lead. It prompted the chess historian Richard Forster to call him "chess player without mistakes." Did Forster jinx him?

When two quarrel, the third may laugh and all of a sudden Kramnik entered the scene. The Russian bear, as if hibernating, hardly moved in the first half, drawing all his games. But he was happy with his good level of play. If he continued to play well without blunders, he was convinced the points would come. And they did. A sudden burst of four wins catapulted him into first place with two rounds to go. Kramnik was leading Carlsen by a half point.

The most dramatic finish in the history of the Candidates tournaments began on Friday, March 30, with three rounds left. The players with the black pieces triumphed and unexpected things happened. Aronian played Kramnik and on move 17 both of them thought they were winning, so complicated was the position, so difficult to solve over the board. Kramnik emerged with a piece up, but misplayed it and Aronian could have forced a draw. He missed it and lost.

Kramnik usually turns questions and answers press conferences into monologues, but not this day. He was so exhausted, he could not think. He wanted to go away and rest.

Carlsen was playing Ivanchuk and up to this game the Norwegian thought he played decent chess in the tournament with very few mistakes. This is an understatement, of course, since stringing games with good moves is not easy. Vassily Smyslov knew how to do it: in his prime he won two Candidates tournaments in 1953 and 1956. Bobby Fischer was another one: at his best, he didn't give his opponents many chances. "As soon as Fischer gains even a slightest advantage, he begins playing like a machine. You cannot even hope for some mistake," said Tigran Petrosian after he lost to Fischer in the final Candidates match in 1971. Carlsen spikes good positional moves with little tactical sequences and does not mind increasing his advantage gradually. He is patient and can wait to claim victories in long sessions.

Vassily Ivanchuk is a dangerous player. In the last 20 years he defeated all the world's best players at least once. Sometimes he is moody and his nerves play tricks on him. Otherwise, he could have been the world champion long time ago. He lost five games on time in London, but his game against Carlsen went on and on. It turned out to be the longest game of the tournament, 90 moves long. It was not going well for the Norwegian most of the time. "I was ridiculously impractical," Carlsen said afterwards. He had a draw at hand after 70 moves, but blundered on his next move.

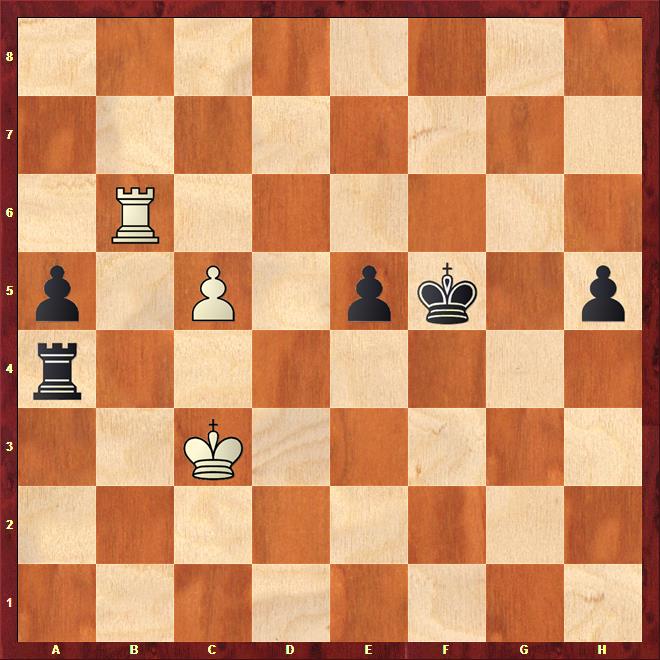

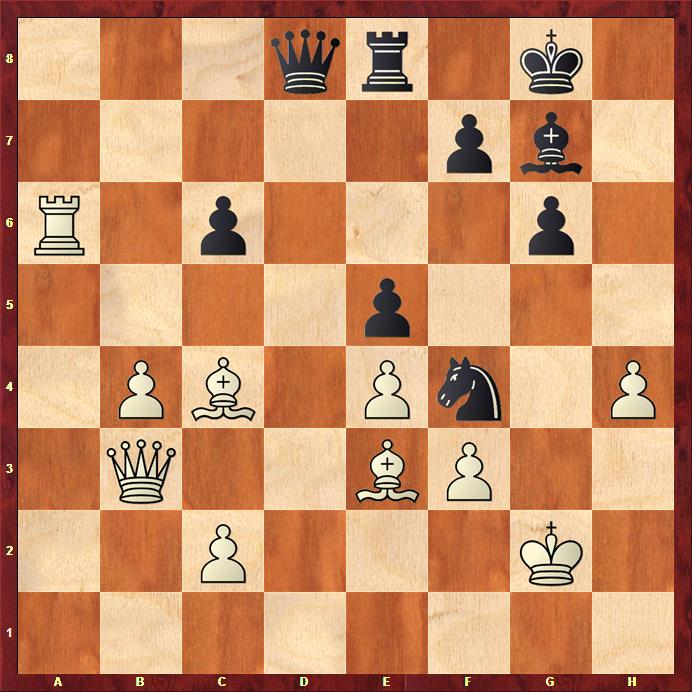

Carlsen - Ivanchuk

FIDE Candidates, London 2013

71.Rh6?

The final mistake. Carlsen could draw with 71.c6! Ke6 72.Rb5! (Threatening 73.Rxe5+!) 72...Kd6 73.Rxe5! h4 (Not 73...Kxe5? 74.c7! Ra1 75.Kb2 and white queens.) 74.Kb3 Ra1 75.Kb2 Rh1 76.Rxa5 Kxc6 77.Ra4 and white reaches the Vancura draw, named after a Czech composer who came up with the concept of attacking the h-pawn from the side, for example: 77...Kd5 78.Ka2 Ke5 79.Rb4 h3 80.Rb3 Kf4 81.Rc3 Kg4 82.Rc4+ Kg5 83.Rc3=; or 77...h3 78.Ra3 h2 79.Rh3 Kd5 80.Rh8 and white has plenty of checks after the black king comes closer to the h-pawn.

71...Ke4

Carlsen missed that the king can walk around his e-pawn and attack the c-pawn.

72.Rd6

After 72.c6 Kd5 73.Rxh5 Rc4+ 74.Kd3 Rxc6 black should win.

72...Rd4! 73.Ra6

White loses after 73.Rxd4+ exd4+ 74.Kc4 d3.

73...Kd5 74.Rxa5 Rc4+ 75.Kd3 Rxc5

Ivanchuk is now winning.

76.Ra4 Rc7 77.Rh4 Rh7 78.Ke3 Ke6 79.Ke4 Rh8 80.Ke3 Kf5 81.Ke2 Kg5 82.Re4 Re8 83.Ke3 h4 84.Ke2 h3 85.Kf2 h2 86.Kg2 h1Q+ 87.Kxh1 Kf5 88.Re1 Rg8 89.Kh2 Kf4 90.Rf1+ Ke3 White resigned.

"It was a reckless move," Carlsen said about his last blunder on turn 71. One move and chess humbles you. You make a mistake early and the suffering goes on and on, and you lose at the end anyway, and they drag you in front of the cameras for a press conference. Be careful what you say, it will be repeated in newspapers all over the world and every burst of anger will be played on YouTube. Even after a decade people will quote you and watch how you sat dejected, sliding down in your chair, hoping to disappear under the table. Finally, you make it to your hotel room, but you are unable to sleep, your brain doesn't let you rest, still working, still spinning out one variation after another.

Kramnik and Carlsen were physically and emotionally spent that day, one from winning, the other from a loss.

In the penultimate round, Kramnik was close to victory. His opponent, Boris Gelfand, was short of time, but managed to find a counterplay, saving a draw.

Carlsen paces himself like a long distance runner. He takes what his opponent gives him and Radjabov makes his first concession only on move 64. Carlsen's manager Espen Agdestein is a bundle of nerves, running in and out of the commentary room. He knows Magnus needs more mistakes and Radjabov delivers. The marathon is over after 89 moves and Carlsen wins. He is back in the race.

Carlsen was in a better position as white to calibrate his play in the last round against Svidler. He played a solid line in the Spanish, but at one point strayed into unclear attacking prospects. The tension resonates in the silence. "Anything can happen when you are tired, when pressure is high," said Carlsen later. "My sense of danger dropped a bit." He lost control of the clock and the position, and Svidler was winning.

But what would Kramnik do against the unpredictable Ivanchuk? He chose the complicated Pirc defence. Like in the King's Indian, you may get one or two chances to escape from a cramped position. Not a great prospect, but what else to do?

The defense goes way back, perhaps to India in the 1850s. We know for sure that Louis Paulsen, the grandpa of many modern opening ideas, played it in major tournaments in the 1880s. Vasja Pirc needed only 25 pages to cover the defense in his theoretical work "The Newest Theory of Chess Openings" in 1959. Today's works are 15 times longer.

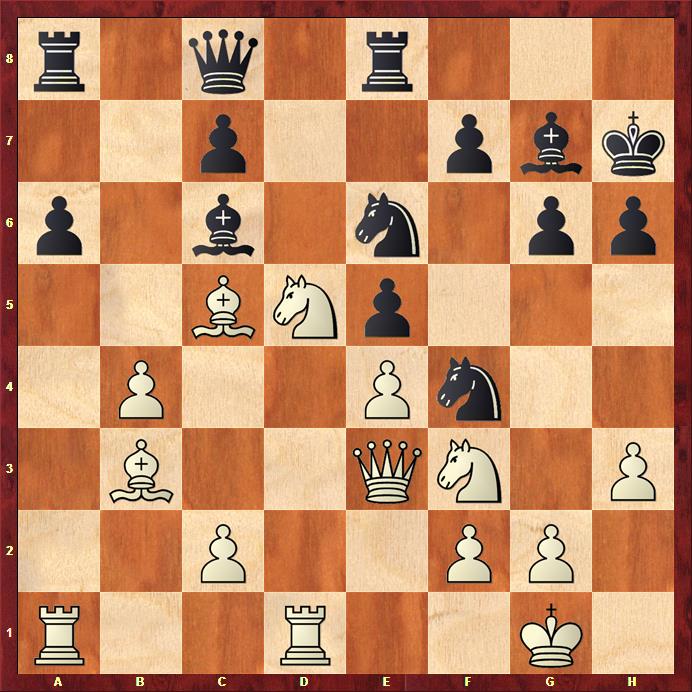

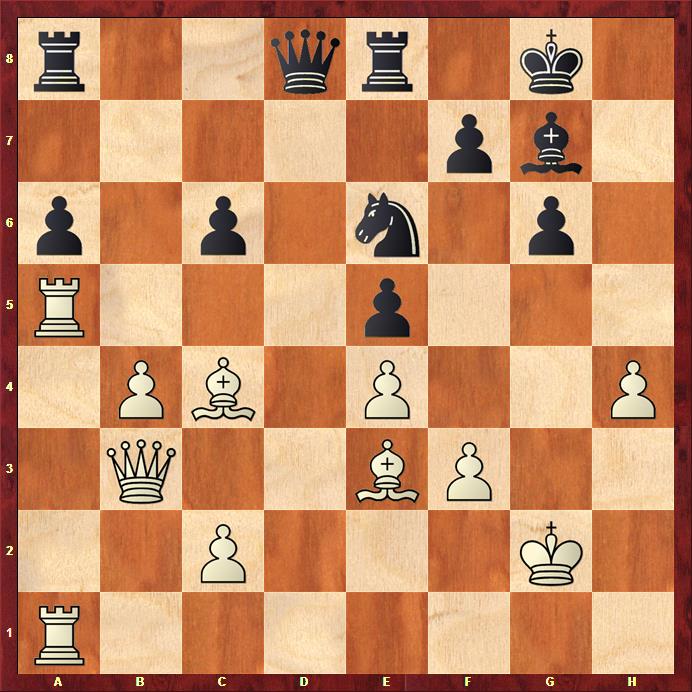

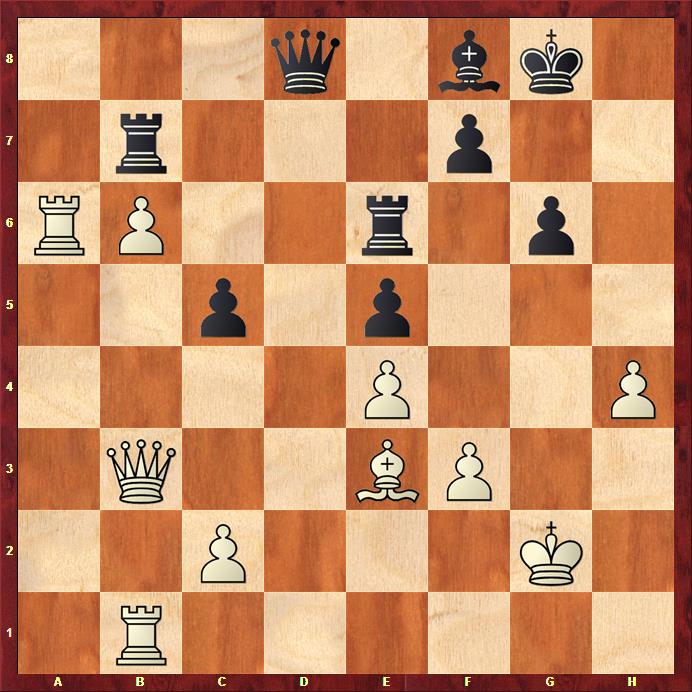

Ivanchuk - Kramnik

FIDE Candidates London 2013

1.d4 d6 2.e4 Nf6 3.Nc3 g6

The Pirc defense didn't surprise Ivanchuk, although Kramnik played it mostly in blitz and exhibition games.

4.Nf3 Bg7 5.Be2

When Mikhail Chigorin reached this position by transposition as black against Leonhardt in Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad) in 1907, the editor of the Wiener Schachzeitung, Georg Marco, called the opening "irregular" in the tournament book. Chigorin came up with the provoking 5...Nc6 with the idea of 6.d5 Nb8!? 7.0-0 c6, undermining white's center.

5...0-0 6.0-0 a6

Signaling expansion on the queen side. When this move first appeared in the game Najdorf-Stahlberg, Amsterdam 1950, Pirc wrote that it was a mistake, a waste of time. Najdorf played the clever 7.Bf4 and met the wing advance 7...b5 with a central advance 8.e5, and after 8...Nfd7 9.a4 dented black's queenside.

7.h3

In 1977 in Amsterdam, Tony Miles played against me 7.Re1 and after 7...Nc6 8.d5 Ne5?! 9.Nxe5 dxe5 10.Be3 Qd6 11.Qd3 Rd8 12.Na4 I was suffering for 74 moves. But I could have tried 7...Bg4, a move Ivanchuk wanted to stop.

7...Nc6

Kramnik bundles together the ideas of Chigorin and Stahlberg. In the King's Indian, the combination of a7-a6 and Nb8-c6 is known as the Panno variation, named after the cheerful Argentinian GM and former world junior champion.

8.Bg5

Ivanchuk wants to make Kramnik's action in the center more difficult and we will soon see why he wants to provoke the move h7-h6.

8...b5 9.a3 h6 10.Be3 e5

Kramnik makes an important step in the center, but Ivanchuk is ready.

11.dxe5 dxe5 12.Qc1

Attacking the h-pawn gives white time to occupy the d-file and win control of the square d4. The computers think that it is serious and they would rather give up a pawn to prevent it: 12...Nd4 13.Bxh6 Bb7 with some compensation.

12...Kh7 13.Bc5 Re8 14.Rd1 Bd7 15.b4 Qc8 16.Qe3 Nd8 17.a4!

Destroying Kramnik's pawn structure on the queenside, Ivanchuk secures squares for his pieces.

17...bxa4 18.Nxa4 Ne6 19.Bc4 Nh5 20.Nc3 Nhf4 21.Nd5 Bb5 22.Bb3 Bc6?!

The first critical position. Kramnik would like to eliminate the pesky knight on d5 and create attacking chances, possibly with a knight sacrifice on g2, but the bishop move is not good. Black should have tried 22...Qb7 or 22...Nxc5.

23.Ra5?

It is hard to imagine that Ivanchuk didn't consider 23.Ne7!, for example:

A. 23...Qb7 24.Nxc6 Qxc6 25.Bd5 Qb5 26.c4 Qb8 27.Bc6 and white wins.

B. 23...Rxe7 24.Bxe7 Nxg2 25.Kxg2 Nf4+ 26.Kg1 Qxh3 27.Ng5+! hxg5 28.Qxh3+ Nxh3+ 29.Kf1 Bxe4 30.Rd8 with advantage. Perhaps Vassily was looking for more.

23...Qb7 24.g3!?

Ivanchuk keeps the initiative with a pawn sacrifice. After 24.h4 Red8 25.c4 the c-pawn blocks the diagonal a2-g8, and black can nearly equalize with 25...Nxc5 26.bxc5 Rab8.

24...Nxh3+

Kramnik accepts the pawn, but one could argue for 24...Nxc5 25.Rxc5 Ne6 26.Ra5 Nd4 with roughly level chances.

25.Kg2 Nhg5 26.Rh1 Kg8

The temporary piece sacrifice 26...Nxe4 27.Qxe4 f5 does not win, but it is an interesting line, perhaps too complicated for human players:

28.Qc4! (After 28.Qh4 Bxd5 29.Bxd5 Qxd5 30.Be3 c5 31.Bxh6 Kg8 32.Bxg7 Kxg7 33.Qh7+ Kf6 and black is safe.) 28...Rad8 29.Be3 Bb5 and now:

A. 30.Rxh6+!? an amazing computer line 30... 30...Bxh6 (30...Kg8? 31.Qxc7! Nxc7 32.Ne7+ Kf8 33.Nxg6#) 31.Qh4 f4 32.Ra1! Rxd5 33.Rh1 Kg7 34.Qxh6+ Kf7 35.Qh7+ Kf6 36.Rh6 Nf8 37.Qg8 fxe3 38.Bxd5 c6 39.Be4 exf2 40.c4 Qg7 41.Rxg6+ Nxg6 42.Qxe8 f1Q+ 43.Kxf1 Bxc4+ 44.Kf2 Ne7 45.Qd7 Qf7 that fizzles out to a draw after 46.Qg4. This is a good example why Gelfand believes the top players get less respect today. Anybody with a computer may outsmart them like this.

B. 30.Qh4! 30...Rxd5 31.Bxh6 looks dangerous, but black can hold with 31...Rd6.

27.Nxg5 Nxg5 28.f3 Bxd5 29.Bxd5 c6 30.Bc4 Qc8

30...Ne6 is suggested by the computers as the best way out.

31.Qb3

Ivanchuk takes his queen away from the kingside to increase pressure on the diagonal a2-g8. But he could have attacked the a-pawn 31.c3 Ne6 32.Bd6 Ng5 33.Qe2 with advantage.

31...h5 32.Be3 Ne6 33.Rha1 h4!

Fighting for the dark squares.

34.gxh4 Qd8

35.Rxa6?

Ivanchuk is letting Kramnik off the hook. He could have secured a slight edge with 35.Bxe6 Rxe6 36.Rxa6 Rxa6 37.Rxa6 Qxh4 38.Ra8+ Kh7 39.Ra1 Qd8 40.c4.

35...Rc8?

Missing the last chance to play for the world title. Anybody with an analytical engine can see a rook sacrifice leading to a draw: 35...Rxa6 36.Rxa6 Nf4+!

Kramnik will remember this position for the rest of his life. White can't win:

37.Bxf4 (Forced since 37.Kg3 loses to 37...Qd1 38.Bxf7+ Kh8 39.Bxe8 Qe1+ 40.Bf2 Qh1; or 40.Kg4 Bf6.) 37...exf4 38.Bxf7+ Kh8! and now:

A. Taking the rook immediately 39.Bxe8? loses after 39...Qd2+ 40.Kh1 (40.Kh3 Qf2; 40.Kf1 Bd4) 40...Qe1+ 41.Kg2 Bd4 and the domination on the dark squares is complete. White gets mated.

B. 39.Qd3!? Qxh4! 40.Bxe8 Qg3+ 41.Kf1 Qh3+ and the white king can't escape the perpetual check.

36.Rh1

White should win now.

36...Rc7 37.Bxe6 Rxe6 38.b5! Rb7

After 38...cxb5 39.Rxe6 fxe6 40.Qxe6+ the insecure position of the king dooms black, for example:

A. 40...Rf7 41.Qxg6 Qc8 (41...Rf6 42.Qg4 Rc6 43.Kg3 Rxc2 44.h5+-) 42.Kg3 Qxc2 43.Rc1 Qe2 44.Rc8+ Rf8 45.Qe6+ Kh7 46.Rxf8 Bxf8 47.Qf5+ Kg8 48.Qg5+ Kh7 49.h5 wins;

B. 40...Kh7 41.h5 wins;

C. 40...Kf8 41.Ra1 (or 41.h5 Rxc2+ 42.Kg3 Qe7 43.Qd5 Qf7 44.h6+-) 41...Rf7 42.c4 bxc4 43.Rd1 Qxd1 44.Qc8+ Ke7 45.Bc5+ Kf6 46.Qa6+ wins.

39.b6 c5 40.Rb1 Bf8

41.Qd5! Qb8 42.Rba1! Rd6 43.Ra8 Rxd5 44.Rxb8 Rxb8 45.exd5 Bd6

After 45...Rxb6 46.Ra8 Kg7 47.Rxf8 Kxf8 48.Bxc5+ white wins.

46.Ra6 Rb7 47.Kf1 Black resigned.

White brings the king to the queenside.

In the end Carlsen and Kramnik lose, but share first place. I don't know if something like this ever happened in such a major event. Winning by losing is a hard concept to explain. In the first Candidates tournament in Budapest in 1950 Isaac Boleslavsky and David Bronstein shared first place, but had to play a playoff match. Boleslavsky was generous: he not only lost to Bronstein, but he let him marry his daughter. Carlsen won outright with a better tiebreak: one more win made the difference.

Kramnik is disappointed. He was so close to winning, but he might not be the most disappointed player in the history of the Candidates tournaments. The legendary Estonian grandmaster, Paul Keres, finished second in three Candidates tournaments in 1953 (tied), 1956 and 1959. Somebody always played a bit better.

One of the most dramatic Candidates tournament in history ended on a day the Washington Nationals started the baseball season. What has baseball to do with chess?

In 1978 I discussed with Bobby Fischer the idea of playing the world championship match to 10 wins without counting draws. "It could take months, " I said. "So what?" countered Bobby. "The baseball season takes more than six months and people follow it." At that time you could still have adjourned games after five hours. Carlsen plays seven-hour marathon sessions without a rest. He may also spend two, three hours preparing for the game. He believes that the 24-game world championship match could turn into a exhausting contest with only one man standing in the end. Remember how Anand and Gelfand were tired after 12 classical games in the world championship match last year in Moscow? It makes you wonder: how could the old-timers have managed to play Candidates tournaments of 28 rounds in 1959 and 1962?

Age could be a factor in the match of two generations. At 43, Anand is one of the oldest world chess champions to defend the title. Is he too old for a title match? At 50, Mikhail Botvinnik beat the brilliant 25-year-old Mikhail Tal in Moscow in 1961. William Steinitz lost his title against Emanuel Lasker in 1894 at the age of 58. Four years later Steinitz finished fourth in a major 20-player double-round tournament in Vienna. "The old Bohemian lion can still bite," the Austrian press wrote about him.

Anand - the Tiger of Madras - is not toothless. He paints himself as an underdog. On paper, Carlsen should win, he thinks. The Norwegian blasted his way to the top spot in the world's ratings at the age of 19. He excels in tournament play and has more energy to succeed in marathon sessions. But Anand has a tremendous match experience and knows how to prepare. His match against Carlsen should be a treat for all of us.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.

Correction: The name of Richard Forster appeared incorrectly earlier. My apology to the Swiss chess historian and fine writer. Many thanks to Edward Winter for pointing it out.

Images by Pascal Simon and Ray Morris-Hill