Earlier this week, a coalition of public health, wildlife, and conservation organizations filed a Clean Water Act lawsuit in an effort to compel the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to issue a rule regarding the use of chemical oil dispersants. In particular, the suit notes EPA's failure to identify the waters in which dispersants, and other substances, may be used and in what quantities. The suit is an effort to inject science and safety into decisionmaking around oil disasters.

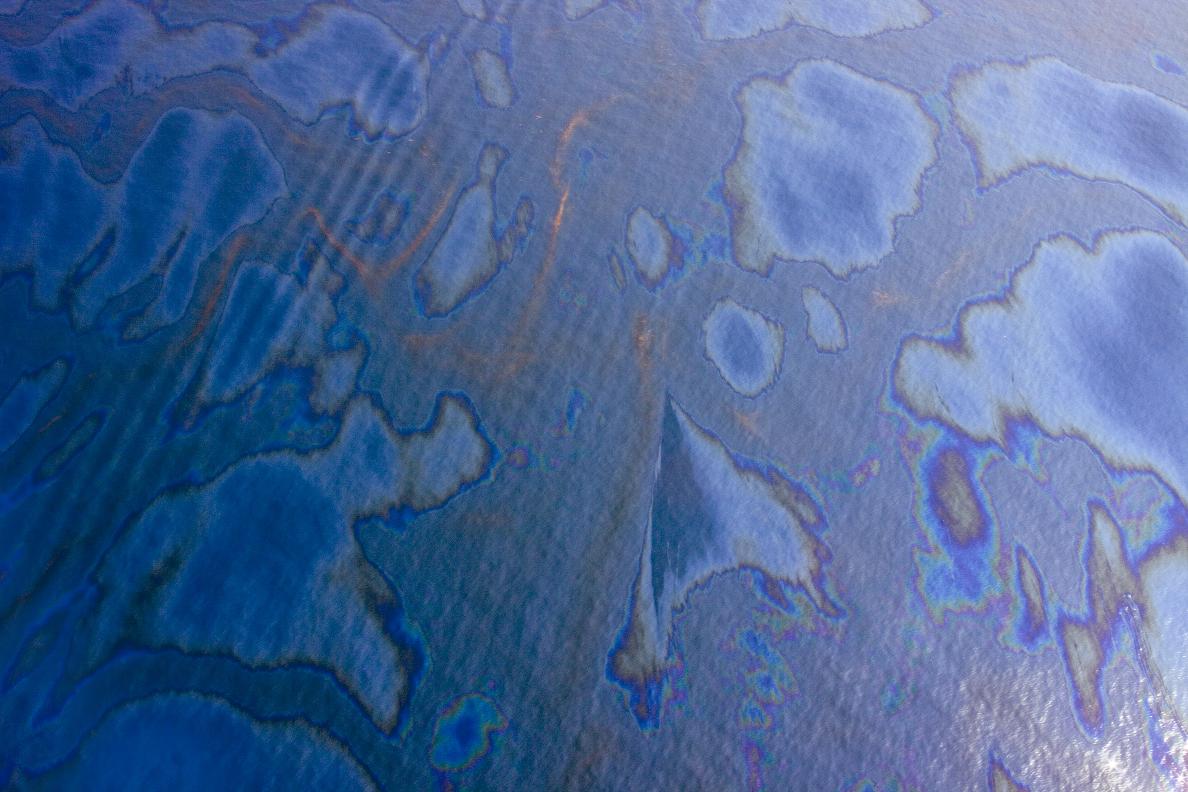

How did we get to this point? EPA's failure to already have taken these actions caused major confusion and uncertainty surrounding the failed response to the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster. In the spring and summer of 2010, BP sprayed nearly 2 million gallons of dispersants into the Gulf. This poisonous brew mixed with the 172 million gallons of BP's toxic oil and turned the Gulf into Frankenstein's laboratory. The dispersants created an optical illusion making the size of the spill seem smaller. The dispersants also made it extremely difficult to clean up the oil, and subjected the Gulf's waters, aquatic life, and communities to unknown long-term threats. According to a recent study, dispersants may have had a very harmful impact on our food chain. In the frantic period immediately following the disaster, it soon became clear that little was known about the health and environmental impacts of discharging these massive quantities of dispersants onto and beneath the surface of the Gulf.

EPA repeatedly acknowledged their ignorance about the effects of the dispersants being poured into the Gulf. EPA statements reflected that science was being done on the fly and that the long-term effects on aquatic life were unknown. The Gulf of Mexico became a guinea pig for the new and untested use of dispersants, substituting the scientific method with a dirty Band-Aid. The result was a haphazard response. Had EPA performed its Clean Water Act duties, it already would have determined in which waters dispersants could be used and what quantities could be safely used. Consistent with the law's intent, various scientific analyses and data would have been available for use in the response efforts.

It is imperative that EPA act now to avoid similar situations in the future. Since the moratorium on deepwater oil drilling in the Gulf ended on October 12, 2010, more than 400 oil drilling permits have been granted, more than 28,000 permanent and temporary abandoned wells in Gulf pose a continued threat, and nearly 38 million acres of the Gulf are being sold off to big oil. Meanwhile, the system for reporting spills is still broken. There have been and will be more oil spills in our coastal waters.

The damage from dispersants in the Gulf has already been done. Nearly two million gallons of dispersants with essentially unknown environmental effects were released into the waters. We need more effective and responsible EPA dispersant rules so that we are never caught unprepared and uninformed in a crisis situation again.

The coalition, represented by Earthjustice, includes Louisiana Shrimp Association, Florida Wildlife Federation, Gulf Restoration Network, Louisiana Environmental Action Network, Alaska-based Cook Inletkeeper, Alaska Community Action on Toxics, Waterkeeper Alliance, and Sierra Club.

Photo by John Wathen, Hurricane Creekkeeper