A couple years ago, when I finally got up the guts to tell a business colleague - a beefy former football player - that a fellow student, a football player, had raped me in college, his gut reaction was a question: "Did you report the guy?"

It was a logical question. He wanted the rapist held accountable, and alerting authorities was, in his mind, the first step to justice.

But I stood there bewildered. How could I explain to this sincere man how distant, on that weekend in January 1979, that option had been? That reporting the rape to the police, or even the school, hadn't even registered on the periphery of my consciousness? That the only action I'd been able to think of was escaping my dorm room -- the scene of the crime -- so I could sort out what had happened.

What seemed obvious to my colleague hadn't been obvious to me. Securing justice in the criminal system is seldom a survivor's only, or even first, objective. Typically, survivors' primary concern in the aftermath of sexual assault is securing their personal health and safety. They want to heal. Sorting out the justice piece will eventually be integral to the healing process, but may not be an initial concern. Survivors have a lot to figure out, a lot of decisions to make, a lot of options to weigh. Determining what actions to take and the appropriate venues for those actions can be daunting.

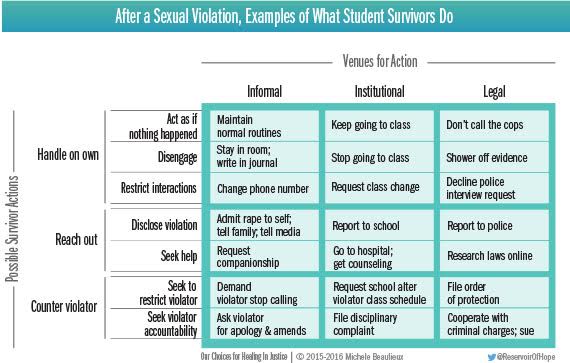

To help people understand and navigate their choices after a sexual violation, I'm developing a decision explorer, Our Choices for Healing In Justice, based on the PrOACT decision-making framework. In Smart Choices: A Practical Guide to Making Better Life Decisions, John Hammond, Ralph Keeney, and Howard Raiffa describe the basic decision elements with the acronym, PrOACT, which stands for Problem, Objectives, Alternatives, Consequences, and Tradeoffs. The matrix above, "After a Sexual Violation, Examples of What Student Survivors Do," is a highly simplified representation of alternatives. The fully expanded matrix has hundreds of cells relevant to survivors in workplaces and homes as well as schools and other settings.

As the matrix illustrates, survivors have a lot of options. They need to decide what to do and where to do it. They can act informally with friends and family; through institutions and organizations like houses of worship, workplaces, societies, or schools; and through the legal system, including criminal and civil courts as well as professional licensing and civil rights boards.

So, where to begin? Survivors often start by handling the situation on their own. That's what I did. Many survivors disengage in order to process -- or avoid processing -- what happened. We stay in our rooms, sob uncontrollably, perhaps write in our journals. The next morning I opted to get out of town. Later, I drew intensely with oil pastels and, sometimes, I still do. In college, I coped solo. I acted the same as I always had, like nothing had happened. I went to class and got respectable grades. I normalized an abnormal experience.

Survivors can also reach out. Eventually, I did. I disclosed the violation, and I asked for help. I told family. I told friends. With this and other posts, I'm publishing my story on the web. I sought and continue to seek help from friends, guidance from spiritual directors, counseling from therapists, and advice from lawyers. In 2012, I told my university's rape prevention center director about the rape. Later, I was surprised and delighted to learn that I had inadvertently made an official report: my alma mater included the rape I had endured decades before as a forcible sex offense -- one of only four -- reported in dorms in that year's Clery statistics. (The federal Jeanne Clery Act mandates that colleges and universities document violent crime reported each year on their campuses.)

Survivors, after disclosing a violation, can try to counter the people who violated them by seeking to restrict them or hold them accountable. The statute of limitations in my state is long past, so criminal or civil legal action is no longer an option for me, but I can seek justice in other venues. In the informal realm, I sent the man who raped me a registered letter asking for an apology. I didn't expect or get a response, but I wanted him to know that I would like one. I also discovered that my college has no statute of limitations, so I continue to ponder whether to file a disciplinary complaint.

As for the straightforward question my business colleague asked, I recently learned that a victim can always report a crime to the police, even after the statute of limitations has expired. I realized I wanted to do everything I could to hold the man who raped me accountable, belated as it might be. So, on a bright sunny day last June, I walked into my local police station, and I reported the rape to an empathetic female officer. Gesturing by hugging herself, she said she understood why I hadn't spoken of the crime back then. "You just turned inward and didn't want to tell anyone, especially your parents," she said. "I get it." This petite woman in blue understood intuitively what many people don't: I was in no position to go to the police back then.

But now, when someone asks me, "Did you report the guy?" I answer, "Yes."

This post is the first in a series on decision-making in the wake of sexual violations.