A Conversation with George Wein

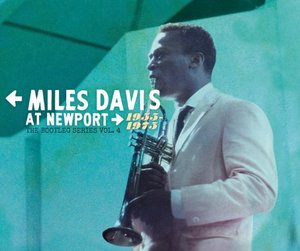

Mike Ragogna: George, you're associated with the creation of the new box set Miles Davis At Newport 1955-1975. What was it like for you the first time you saw him at Newport?

George Wein: This was back in 1955, and Miles didn't have a band. I was in a club one night in New York and he was there and we announced the lineup for the second Newport Jazz Festival. Miles says, "Hey, you're doing a jazz festival in Newport? Well, you can't have a jazz festival without me," so I said, "All right, I'll call your agent." I put Miles on the festival. He wasn't even advertised, I had to put a band together. It was Thelonius Monk on piano, Gerry Mulligan on tenor saxophone--I think Zoot Sims was there, I'm not sure--and Connie Kay and Percy Heath on bass. They played a set and Miles put his horn up to the microphone and played Thelonius Monk's "'Round Midnight." It was the hit of the festival. He came off the stage and people were signing him up to record deals. The only thing he had to say was, "Tell Monk he plays the wrong changes to "'Round Midnight." That's all he said to me.

MR: [laughs] Did you feel like you were watching magic as it happened?

GW: You know, one of the problems I have is when I was making history I didn't know I was making history, I was just trying to make things happen. We didn't realize that even when Duke Ellington had that fantastic night that rejuvenated his career and everything we just said, "Hey, it was a great show!" I never thought like that, I wish I did. I would've paid more attention to it.

MR: What made Newport become the showcase for up-and-coming and established jazz and folk acts?

GW: My job is to provide a stage for the most talented people I can find and present at any given time. If they're all unknown it's still my job to find them a stage to be heard. That's what we did from the beginning.

MR: What is it about jazz that you love the most?

GW: Jazz was a part of my life from the time I was thirteen or fourteen years old and I learned how to improvise. I was magically affected by that. Then when I heard different records and heard this music just reach into my head and never get out of there, I guess I wanted that to be my life.

MR: As a player what was the magic? Are there artists who influenced you?

GW: I was very impressed by Teddy Wilson and Benny Goodman at a very early age. Then I got on board with Ellington and Armstrong before bebop and before Miles. So they're a product of the swing era, actually.

MR: It could actually be said that Miles was as well.

GW: Well, Dizzy was particularly a product of the swing era, he played with Cab Calloway's band. Miles, I don't think he ever played with any of the great big bands like Dizzy did. Miles was my age, and I was an anachronism to a degree with people my age because I spent three years in the army from '44, '45 and '46 when bebop came on the scene, so when I came out of the army I said, "What is happening to music? I don't know any of this music!" So that was a difficult period for me. It took me a few years to realize how great Charlie Parker was.

MR: And then there's that classic period you participated in heavily, which was about '58 through '64 or so when Brubeck and Davis became hugely popular. Do you think that was a product of marketing or a product of the culture finally discovering great jazz?

GW: Brubeck became popular for one reason only. His music reached people in a way that other jazz didn't. Brubeck had a more classical approach and people had been more conditioned to classical music growing up and here was this man playing jazz and they heard something that they could relate to. From the minute he came to Storyville in 1952 in my club, opening night, nobody knew he was there. But by the end of the week, the place was full, just by word of mouth. What he was doing communicated. When music communicates, it doesn't need promotion. It needs promotion after it communicates to take him to another level.

MR: There's always been an emphasis on hearing jazz live, I guess mainly from the improvisation--that once in a lifetime performance that happens in the moment. I think you tapped into that energy with your venue.

GW: Well Brubeck did a lot of live recordings that were very important to him, Jazz At Oberlin and Jazz At Storyville. They were very important to his career, but live jazz recordings are what brought Miles back. The one at Newport was a bootleg recording, Columbia didn't even record it but they have it now because they got the tapes. I think that's part of one of the albums they're putting out in this package they're putting together.

MR: Intellectually, were you following what Miles was doing with his career and all the changes that occurred within his creativity?

GW: Of course, I had to. Whether I wanted to or not, I had to! [laughs] Remember, we brought Miles back after he had been out for about five years. He came into my office, he lived around the corner, and I wrote him the check for thirty-five thousand dollars and gave it to him and said, "When you're ready to come back I want to do two concerts with you at Lincoln center." He looked at that check and he couldn't believe it. It was a big gamble, he could've cashed that check and taken the money, but he gave that check to his manager and his manager called me and said, "Why did you give that check to Miles?" I said, "Because I feel he should come back and play now." But when he came back and played, it was the music he had been working on. It was an electronic approach to his music, it was different from what he'd been doing before. He used used to come in and play these tapes for me and that's when I said, "I think you're ready." Ever since then, Miles and I were very, very good friends. We worked closely together.

MR: By his playing you material and by your believing in him, that was, in a way, supporting and participating in helping jazz fusion take root in his music, no?

GW: Well, I've said this for decades: jazz is like a deck of cards, you need the aces. Miles was an ace and you needed to keep him alive and keep him going. You needed him in jazz because he was very important, so helping to bring him back was something I felt we needed to do.

MR: With all the momentum that these amazing artists had and the mark they left on many great musicians, why isn't jazz the most popular music of the country?

GW: That's a tough question, because I look at this way. Classical music sells the least records of any kind of music on the market with the exception of jazz. Classical music is accepted as a great music that will always be with us, and jazz is now accepted as a great music that will always be with us. It's never going to disappear. It may not be on top of the charts, but jazz is now an accepted part of our cultural life. It isn't necessarily relating to popular music anymore. You're not going to make a lot of money as a promoter of jazz. But you'll sure hear a lot of good music.

MR: Where do you think jazz is heading?

GW: I think some voice, some sound will emerge that will communicate to many people the way Coltrane came out, the way Charlie Parker came out, the way Armstrong came out in their different eras. There's no leader now, there's no one voice that people look to as the spokesperson for jazz. You have Winton Marsalis as the great leader of the jazz at Lincoln center but it's not his musical voice that is the leader and that is what's needed. When you get that, you'll find a new surge in popularity for jazz.

MR: Yeah, I think you're right. Do you think it will need to be appointed or is it something that will happen naturally and we just have to wait?

GW: You can't appoint the kind of leader I'm talking about; it just has to evolve naturally. Nobody can appoint that kind of leader.

MR: At this point, do you have any thoughts on who might be it?

GW: No, I haven't got the slightest idea. If I had, I'd let you know. I wish I could find them.

MR: You've done so much to keep jazz in our culture, did you ever think you'd be doing such important work?

GW: Not at the time. I like to think that now, because that's our mission now, but I didn't think so at the time because I was just a jazz fan. I was just privileged to put these people that I loved on a stage. It was exciting for me, it was an adventure for me, and maybe that's why it was important. It wasn't a business, it was an adventure.

MR: Do you have a couple of favorite memories of concerts at Newport?

GW: I have a stock answer for that actually, because the best memory of any festival is when it's over and you know you're going to do it again the next year, that is always a beautiful memory, but in the music itself, both folk music and jazz they do finales, like with Pete Seger and all those people on the stage singing "We Shall Overcome" and the effect it had on our civil rights movement that was very important. In jazz, what Ellington did in '56 and Mahalia Jackson singing gospel and then just recently Winton playing with Tony Bennet and Dave Brubeck and particularly Winton with Brubeck when it was Brubeck's last performance. These were very moving moments.

MR: People must come to you a lot and say, "Here's the next thing we should do with Newport!" Do you chuckle to yourself about it since you already have your very successful paradigm set?

GW: No, I listen in a lot of cases and I dismiss it ninety-nine times out of a hundred. But that hundred might be a good idea.

MR: A question about the folk festival. How did that begin?

GW: I learned from New York, the Village Vanguard and Café Society used jazz people and then Josh White might be there or Pete Seeger might be singing there, so I had the opportunity to do that in Newport. One day, I brought in Odetta, who I never really knew anything about and all of a sudden, I saw hundreds of young people coming in the club that had never come before. I said, "Hey, there's enough here for a festival," and that's when I decided we should do a folk festival.

MR: Nice. George, what advice do you have for up-and-coming artists?

GW: I get that question a lot. I've got an up and coming artist right here in the room while we're talking. Get out into the music community and get them to know what you can do. Beg, borrow and steal a few moments when they can hear you play and hear you do something because the greatest talent scouts are other people in your field. They tell other people, "Boy, I just heard a great young drummer you should pay attention to if you're making records." That is always happening. The greatest proponents for new music are other musicians because they get impressed when they hear somebody and they tell other people.

MR: Did Miles ever thank you for finding him that band?

GW: Yes. You have to accept this for exactly what Miles is. He said to me once, "George, you're a mother f*cker, but you're the best." He really said that to me. I put that in my book.

[NOTE: The Newport Jazz Festival will be held July 31-August 2. It will celebrate Miles Davis' relationship with George Wein while honoring the 60th anniversary of Miles' Newport debut with musical tributes, workshops and more.]

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

*******************************

FIRESHIPS' "COME BACK TO ME" EXCLUSIVE

According to Fireships' Andrew Vladeck...

"The title of this video could just as well be 'Last Days of the Family Homestead.' I wanted to do something special to commemorate the home--and the room--where so many wonderful family moments happened, and the room where I wrote much of the record. The time had come for my mom to put our home in the woods up for sale. I rounded up my band for a farewell concert. The song is 'Come Back to Me, in which through love and loss you are still surrounded by the landmarks of your home around you. You might recognize a different neighborhood referenced in the song--having moved out of the family homestead to New York City some years ago."

******************************

A Conversation with David Benoit

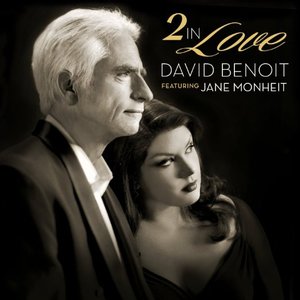

Mike Ragogna: David, are you 2 In Love?

David Benoit: [laughs] Well, it's all about the song, the great lyrics by Lorraine Feather. She kind of said it all. I thought it was a clever name for the record.

MR: This is the first David Benoit album for which you co-wrote virtually every track.

DB: Yeah, that's definitely true. The interesting was it was at the suggestion of the label. They said, "We have to do something really different. We've done so many records with your name, what can you come out with that's totally different?" Then I started formulating this idea of a vocal album. The whole concept of it, just having me on the cover with Jane Monheit 2 In Love is just a completely different concept, it's not some generic artwork on another David Benoit record that's kind of piano instrumental. We wanted to do something really different but also something very honest. I love vocal music. A lot of my heroes are Burt Bacharach and John Barry--the guy who wrote all the James Bond themes--and Cole Porter. I've always liked really strong melodic vocal music, so this was a chance to indulge myself in that.

MR: Why did you choose to record 2 In Love album with Jane?

DB: It was actually the label's suggestion. They suggested her and it was fortuitous that right when they suggested it I happened to be doing a concert at KJAZ radio in Los Angeles and she was the opening act. I knocked on her dressing room door and I said, "Hey, do you want to do a record," and she goes, "Yeah!" The planets kind of aligned for that one. It just felt like the right thing, and she really was the perfect choice because her vocal range is so amazing.

MR: Another interesting element of the album is how you combined your talents with a couple of your label mates, of course Jane but also Spencer Day, a relative newcomer.

DB: He's a newcomer definitely in my world, I've been writing with Lorraine Feather and Mark Winkler for years, I only met Spencer Day two years ago, but I was just really struck by him. I'm not always impressed by people easily but he just has a beautiful voice and all of his lyrics are very sensitive, he's a great writer and a really nice guy and I was just struck by him. I said, "Hey, do you want to write some songs together," before I even had the vocal idea. I just wanted to do something with him because I liked his energy and he said yes and he liked my energy. We had done a couple of dates together with Peter White and we just had some good chemistry. That was really fun, hooking up with Spencer.

MR: The only track that you didn't write on the album was the "Love Theme From Candide/Send In The Clowns," and you dedicated it to Betty June Benoit, that's of course your mom, right?

DB: Yeah, that was mom.

MR: Why those songs?

DB: Her two favorite plays in the world were Candide and A Little Night Music, which "Send In The Clowns" is from. She loved musicals. Candide was her absolute favorite. She loved Leonard Bernstein. I heard it all growing up. I always wanted to do that. I've conducted the piece as a symphony piece and it's a magnificent piece, but I thought, "How could I do that on a record album? Well, I'll take that middle section of "Love Theme..." and turn that into a piece," and then I married that with "Send In The Clowns," which my mother also liked. I thought that was a little tribute to her eighteen years later after she died, but I'm finally getting around to it.

MR: That's sweet. I imagine Bernstein, Sondheim and Bacharach all have big influences on your songwriting, right?

DB: Oh definitely. Leonard Bernstein was an amazing songwriter, if you think of all the pieces he wrote for West Side Story and then even On The Town and, of course, Candide, there was great song structure, high melodic content, and really interesting use of harmonies. He was a big inspiration as a writer. Even Dave Grusin, who's more known as an instrumentalist but is known for "It Might Be You," he has beautiful songs, so his influence was there as well.

MR: You've recorded so many albums, why did it take until now to do something more songs-with-lyrics based?

DB: It's a good question and I probably don't have a specific answer for it. For a long time, I was really trying to expand as a composer of all this classical music. I did an album of all of these symphonic compositions years ago that didn't really sell anything, so then I kind of went back to chill music and I was experimenting with this new bossa nova sound. I was just trying a lot of different things. In the back of my head I had wanted to do this for a long time but sometimes it just takes a little encouragement. I think the label had a lot to do with it. I even had a conversation with Dave Koz about it, he had encouraged me. Maybe it was just my own insecurity that I didn't think I could pull it off but he was saying, "Yeah, you had a whole career of accompanying vocalists," and I did years ago. This is in another lifetime, when I conducted for singers like Lainie Kazan and Connie Stevens and even Diane Schuur and all those people. I developed Patti Austin--I'm name dropping here, but I did get some chops as an accompanist, so that was kind of fun to explore that side, which I haven't with any of my records. I guess those were also reasons. I don't know why it took me so long but I'm just glad I was able to finally get around it.

MR: When you look back at your catalog, there are songs that are so melodically driven they lend themselves to being pop songs. Have you ever thought about going back with someone and seeing what lyrics could be added?

DB: That's a thought. I did cover an old instrumental tune of mine, I thought it would be fun to bring back a tune, "Love In Hyde Park." It was originally called "A Moment In Hyde Park" and we changed the title to conform more with the theme of this record. That was on my second album, so I wrote that in 1980, a long time ago. That was with a big orchestra, this is a more intimate reading of that tune with Tim Weisberg playing the beautiful flute. But yeah, that's a thought. I'm probably more forward thinking, I'm actually working on a few other projects that I'm trying to get funded. One is an interesting thing I'm still in the middle of. It's a piece called "Bike Ride." I'm starting to get really inspired by choral music and this is a piece for a boys' choir. It has a little story to it; it's about a boy who gets bullied and his bike is his refuge but the bully steals his bike so his dad comes and helps him get it back. It's kind of a little autobiographical but I'm working on getting that project funded right now, but that's inspired me to think forward and do more interesting things and push the envelope.

MR: These days, there's certainly a bigger spotlight on bullying in schools.

DB: It could be very timely. I have this chorus called The All-American Boys Chorus, we did some Christmas projects together, I'm looking to get a commission to perform it. As soon as I get it done I'm going to send it to them and I know they will probably have some avenues to get the piece some recognition. It is very timely and it's very, very personal. I wrote all the lyrics myself and I'm not a lyricist but I drew upon experiences as a kid. I thought I was the only one who could probably do it because I had those experiences of being bullied and fortunately I was able to discover playing the piano as a way to help my confidence. It's written for boy choir and piano and I'm eventually going to orchestrate it but the piano plays a very central piece so that's something that's very dear to me and I'm hoping to get it finished soon.

MR: Do you feel 2 In Love has affected you in other ways? Has this project changed how you now approach writing?

DB: In a way, it has. It's kind of freed me up a little bit. It may sound funny, but I think for a long time I was trying to chase the tail of radio. "Okay, is it smooth jazz? Now it's chill or house, let me get a groove and a drumbeat." This album I said, "Screw all that, I'm just going to write songs. I'm going to get back to what I love to do. I'm not going to think of a radio format or try to conform or anything, I'm just going to write good songs. The other thing is I didn't want to do cover tunes. How many times can you keep covering The Great American Songbook? Let's write some new stuff! It's kind of freed me a little bit to get back to writing stuff that gives you chills or emotions. It's been a catharsis in a sense.

MR: Are you more tempted now to pick up the phone and say, "Hey, let's get together for a songwriting session," with other lyricists you admire?

DB: I remember years ago, I wrote a TV theme with Marilyn and Alan Bergman, two of the greatest songwriters. I still have people telling me, "You should've just picked up the phone," because he wanted to write something but I just couldn't get the courage up. There's a lot of great writers, I also have friends at Disney so I thought maybe I'd send this record over to Chris Montan, head of music at Disney. I can actually hear a couple of these songs in Disney films, like "Fly Away" or some of the Spencer Day pieces especially. I've been thinking about that as well.

MR: After following your work for so long, I'd say you could get the same kind of work Grusin was getting. Are reasons you haven't followed that path?

DB: It's true, in looking back, my dream was always to score movies, and I did it for a little while, but I can't put my finger on why exactly that part of my career didn't take off. It's weird, sometimes you just kind of follow your fate and my fate was playing "Linus & Lucy" and "Kay's Song" and "Free By Midnight." I've been lucky there, but if there was a little regret, I really wanted to be Dave Grusin, I wanted to be John Williams and Leonard Bernstein. Those are my heroes. I don't mean any disrespect to Herbie Hancock or Chick Corea or Ramsey Lewis or Brian Culbertson, for that matter. But that's not my thing. My thing is Leonard Bernstein. My thing was André Previn. In a way, 2 In Love is starting to move in that direction. I just want to write some music that could be in a Disney movie or on a Broadway musical stage. Even when you listen to the record you'll notice little sections that go out of time. As if a smooth jazz tune would ever not have a constant drum beat to it. That was fun. On "Barcelona Nights," we just stopped all the time and had a solo guitar in the middle of the tune. [laughs]

MR: You said the label had a monetary motivation for you trying something new, but as a creative artist, do you also think it's time to do something different?

DB: I do. Now it's really about me making sure that at sixty-two years old, I'm maintaining my health and I'm in good shape because I could have another twenty or thirty years. You hear more and more artists that in their later years are putting out some of their greatest work. I really feel that I'm just on the dawn of doing cool stuff. It's been a really interesting creative time for me, writing this piece "Bike Ride," and I've got a series of piano études. The hardest part is the business part. Getting it funded, getting people to listen. At least I got 2 In Love out there. One thing I didn't want to do is make my own label. So what? So I can make an album? If nobody knows about it, what good is it? I'm glad that Concord was willing to invest in the 2 In Love project and I hope that'll be the spark that ignites a bigger fire maybe.

MR: Were there any moments on this album where you were really floored by Jane's performances?

DB: I expected she would nail everything that she did. But I wanted to stretch the boundaries a little bit and get out of smooth jazz for this thing, so there was a tune I had written that was in development for a Broadway musical called Something's Gotta Give. I didn't know whether she would come from that space of drama. There's a line in the song towards the very end where she makes a statement and everything just stops. It's very dramatic and you'd never hear it on a smooth jazz album, god forbid. It was a moment for me of like, "Wow." Jane was the perfect choice because she totally understood that drama that you might only understand if you went to a Broadway musical. In fact, I'll mention to you that one of the things I want to do is a little staged black box theater presentation of the record where it would just be lit and staged almost like a little Broadway show. That's something I've been talking to Mark Winkler about.

MR: Would you be tempted to write a couple of pieces for that night?

DB: Yeah, definitely! It might be fun to write a couple of new pieces and make it evolve into more of a real story.

MR: Did the two of you become closer during the recording process?

DB: Yeah, I think, in a sense. It was funny on the photo shoot, the intimate moments in front of the camera. She's funny, she would get very seductive in front of the camera and then as soon as we were on a break she'd go, "Okay!" that's kind of an aside. I think musically is where there was a strong connection. Hopefully I think Jane felt the same thing, that she related to my music and was able to really bring it to life. It means nothing unless somebody is really able to do that, and she was able to do that. We got to hang out a little bit too. We had a little listening party at my home and she happened to be in town so she came to that and it was a lot of fun, we had a great time. Unfortunately, she's had a family incident or some kind of issue come up and we've had to cancel a couple of dates on the West Coast, which I was very sad about, but I understand. Hopefully that will get resolved soon and she'll be able to come back out with us.

MR: What advice do you have for new or emerging artists?

DB: Find your own sound. The good news is there are all sorts of schools and colleges and institutions where you can learn just about anything about anything. Learn How To Play Like David Benoit is probably a whole course somewhere, but I listened to a lot of Bill Evans, John Berry, Leonard Bernstein, Sérgio Mendes, Cat Stevens, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, that's how I developed my sound; by listening to all different kinds of people. I do see that a lot of artists get confined and say, "I'm traditional bebop, I'm traditional jazz, I'm not going to listen to anything but that." It's become really stratified. What happened to just listening to it all and being open minded whether it's Albert Ayler or Kenny G?

MR: Bu the way, I've seen you play live a few times and the amount of energy that you bring to a stage is surprising. You play your ass off from beginning to end with virtually no break, unlike most artists that are categorized as "smooth jazz." God, I hate that term.

DB: [laughs] I know.

MR: But how do you keep that energy level up, especially over all these years of performances?

DB: That a good question. I did actually run into some health issues about two and a half years ago and it really made me put into perspective that energy level. There was a pattern years ago of getting really, really up for the show, drinking massive amounts of coffee and then, when the show was over, going the other way for massive amounts of alcohol. It was creating this situation of high blood pressure that went unchecked and then I got sick. My biggest fear was that I was going to lose all that energy, but in fact after a year of recuperation I'm feeling better than ever. I get energized when I play, I think the audience energizes me. And on that subject, in seeing a lot of the more recent smooth jazz acts I feel sometimes the emphasis is more on theatrics and dancing and clapping your hands. I still feel the energy should come from the instrument, so I put a lot of energy into the playing the piano and when people react to it and get excited that's when I feel really good. I don't put the energy into a wireless mic or asking the audience to sing along with me or prancing around the stage. Acts that do that aren't my thing.

MR: And that seems to coincide with your musical favorites.

DB: Yeah. I was mesmerized seeing Bill Evans, he'd have his head down but he'd play so beautifully, or seeing a classical pianist like Lang Lang with so much energy coming out of that instrument. That's my personal feeling. It's been tough because I know smooth jazz hasn't necessarily rejected me, but it's been a community that no longer wants to get grand pianos, "We'll play the controller keyboard." Uh, no, I'm not going to give in on that. I'm going to have a nice black piano on stage. That's my instrument, you know! [laughs]

MR: Do you feel like Bill Evans might have had the most influence or inspiration for your stage presence?

DB: Partly. Here's the interesting thing. My hero Dave Grusin doesn't quite have the stage presence that Bill did or I do or that Chick Corea has. You can see that that's not a comfortable arena for Dave and I've talked to him about that. When he goes out on the road he usually has Lee Ritenour front and center and he kind of hides behind him a little. It's funny I should say that, but not all artists are necessarily comfortable as performers. Dave's my hero and my friend, but I've made that observation, as opposed to someone like Dave Koz where it's all about the stage. Dave Koz is a really great performer and knows how to get the audience to go crazy. A lot of his show is involved in that happening. Bill Evans was all about that instrument and getting sound out of it, getting very, very intimate.

MR: Would you ever try to record a whole project of David Benoit music with David Benoit lyrics and David Benoit vocals?

DB: I'm experimenting right now with maybe singing a couple of the songs on a few performances. A song like "Fly Away" is right in my register because Spencer wrote it. For years, I stayed away from ever trying to sing, but as I've gotten older I've thought maybe if I worked on it a little bit and approached it like Burt Bacharach did or the way Herb Alpert did, saying, "I'm not a singer, but I am the songwriter, I wrote this music and it comes from a very sincere place, so maybe it's okay if I sing at least a couple tunes."

MR: I think you might have a good time with vocals.

DB: It could be. I have another career as a DJ so my voice is now familiar to people on the air, so it's not that much of a stretch these days. I remember years ago on a record date I had tried singing a song and I wasn't prepared and the producers were kind of laughing at me and I got a stigma about it. That was about thirty years ago and I said, "Oh, I'm never going to do this again." Now I'm kind of beyond that. it's funny how you get the little stigmas going. I've got a date next week in Cleveland, it's a promotional date for the record and I think I'm going to make my debut there as a singer. I'm going to try to sing "Fly Away."

MR: One last thing. What was it about your album Freedom At Midnight that keeps it popular to this day?

DB: Well, I remember when USA Today put it on their cover, I went, "Wow, I must be doing something right!" When it hit the mainstream of America, I wasn't just a jazz guy living in California trying to hustle gigs, I had become somebody that people recognized around the nation. It was a big thing for me, but if I go back on all the thirty four records I have done, that's one of the best. I think all the planets just aligned on that one. Nathan East... And Jeff Porcaro was alive and I was lucky to get him. Jeff Weber, to his credit, put together a good team with Allen Sides and I wrote "Kei's Song" because I had just married my wife; it was just one of those records! Every artist has a record like that in their career that's just a defining album.

MR: Were you ever tempted to follow it up with More Freedom At Midnight?

DB: Yeah, there's always the sequel, but I think we just kept trying to evolve from that, so every next album was a natural progression from that. Then I tried experimenting with a lot of other different things and the story has been told there, but Freedom... is just one of those records and I'm lucky that I had it. Every artist needs some kind of record in their career that defines them.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

******************************

DELTA DEEP'S "DOWN IN THE DELTA" LYRIC VIDEO EXCLUSIVE

According to Delta Deep's Phil Collen...

"Delta Deep is an extreme blues band where the expression of anguish mirrors the true meaning and origin of the blues unlike the adapted stylized, glossy versions of blues that we hear today. We are putting the soul back into soul music. Being a true artist means that you don't have genre-specific limitations. Delta Deep is a fusion of soul, gospel, blues, funk, rock 'n' roll, punk rock and most of all feeling."

******************************

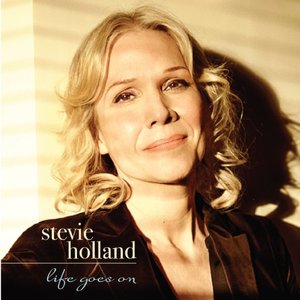

A Conversation with Stevie Holland

Mike Ragogna: Stevie, you're considered one of the great interpreters of Cole Porter, his material being the focus of your one-woman, off-Broadway show, Love, Linda: The Life of Mrs. Cole Porter. What originally drew you to Porter's repertoire?

Stevie Holland: Hi Mike, I've always found Cole Porter's lyrics to be the sexiest and most provocative in the America Standard Songbook, and his music to be innately influenced by jazz. In addition to his great music, what specifically drew me to writing LOVE, LINDA, was that although Cole Porter was gay, he had a meaningful companionship, love, and 35-year marriage to a woman, Linda Lee Thomas. So I set about telling their story through her eyes, weaving dialogue and Cole's songs--taken out of their original intended context--together, with the hope of creating a compelling narrative.

MR: Your new album Life Goes On, contains such familiar, older material as "Skylark" and "Tea For Two" as well as modern classics like "99 Miles From L.A." and James Taylor's "Another Grey Morning." How did you make the song choices for the album?

SH: "Skylark" and "Tea For Two" are of the more recognizable songs I cover, as I usually strive to seek out lesser-celebrated material that I think deserves to be heard.

Each song on this album, including my originals, has been in my heart for many years. The challenge is choosing which songs will flow well together, cohesively, in an album. Though I pretty exclusively choose my material, Todd Barkan shared Benard Ighner's "Life Goes On" with me, and its poetic statement resonated so deeply. This is the second time I've recorded a James Taylor song. A few CDs back, I covered "Sunny Skies." It looks like I'm vying for the role of his weather reporter!

MR: [laughs] What do you look for in a song before you cover it?

SH: The lyric has to be meaningful, and well crafted. No matter how beautiful the music is, if the words don't speak to me, I can't sing it.

MR: What is your musical education?

SH: My Mother was an operatic soprano, and though my Dad traded out the sax for a career in commercial art, he was an avid jazz buff, who made sure his kids knew the difference between Ben Webster and Charlie Parker. I studied piano, guitar, then voice, privately for years. Ultimately, I chose drama as my major in college, but continued with voice, moving from a classical repertoire to contemporary material.

MR: What influenced you to start writing lyrics?

SH: I also grew up in the heyday of the singer-songwriter, and between my love of so many of those artists, as well as the great lyricists of the American Standard songbook, I was inspired to tell my own stories. My most meaningful collaboration has been with my husband, composer Gary William Friedman.

MR: What was it like working with Todd Barkan at the helm again?

SH: This is our second CD together. Todd's ears are infallible. He's an incredibly knowledgeable, and informed musician, and both Gary--who did all the arrangements for the album--and I, trust his acumen, across the boards. I also rely on Todd to tell it to me straight, and to help me make sure I'm keeping true to the story of the song.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

SH: My artistic credo is to stay true to your instincts and strong in your beliefs, pursue only original paths, and listen to the one thing that will never steer you wrong: your heart.

MR: Is there another composer whose material you'd like to feature within another one-woman musical?

SH: I'd like to feature my husband Gary's, music, and also play him, as a woman. Seriously, we're working on a pared-down adaptation of an early Broadway musical of his, entitled Platinum.

MR: What's next on your plate?

SH: Setting up tour dates for Life Goes On with the brilliant musicians who performed on the album, and continuing to develop a screenplay and musical that have been in the works.

******************************

LABOR CAMP'S "NOSTALGIACIDE" EXCLUSIVE

According to Labor Camp's Kurt Schellenbach...

"Overall, I see Labor Camp as an alternative creative outlet for me that's not driven by any commercial considerations but is my own thing allowing me to work with great musicians again. In a sense, I would say that I'm free to do whatever I want musically and take my work into the studio, composing and producing it any way I want. Now as then, I'm not trying to be some big rock star. But I'm grateful to be making music that's fun and fulfilling."