President Obama can learn a lot from visiting Brazil, specifically regarding their need for efficient and extensive public transport systems, a dynamic demand for housing for the burgeoning class ascending out of poverty -- likely a 40-year project -- and the need for a complete overhaul of public education. Similar to the bet on modern architecture in the 1950s by then President Juscelino Kubichek in his aim to build the city of Brasilia as emblematic of the nation's transition to a modern state, President Obama could understand what the United States will face if it doesn't address its problems simultaneously.

The people's deep attachment to the concept of nation in Latin American cities like Mexico City and Brasilia forms an aesthetic and spatial bond with the architecture that symbolizes that connection. The "substantial freedom" that philosopher Georg Hegel describes in Philosophy of Right underscores the thickly social dimension to political and social connections whereby the individual needs to be invested in some sort of social institution in order to fully achieve the ideal of freedom. In Brasilia the utter optimism of the architecture -- from the Itamaraty Palace to the Presidential Palace -- exude transparency and lightness, even while deploying vast amounts of concrete to achieve this. The public imagination is embroiled in the country's ascension from a colonized state into a self-sufficient economy and now its day has come!

The dominant urban landscapes of Brazil's largest cities are modern buildings, public spaces, and favela slum communities. Brasilia and Rio de Janeiro are the boldest examples of the paradoxes still left to conquer for our hemisphere's second largest economy. The elaborate urban stage of Brasilia -- with a central spine of open space that perceptually dwarfs Central Park and the Washington Mall, its flanking rows of government office buildings on each side of this central space, its two halls of congress shaped like half ovals, and the twin office towers of less than twenty stories that house congressional offices -- is as remarkable as it is tragic. Experience the space, and you find vast swaths of land between you and the next building, 6-lane highways that are difficult to navigate, and a city disciplined by sector-by-sector zoning that segregates hotels from offices, housing from car dealerships. My first thought was, is this Los Angeles on steroids or what?

The gem in the whole scheme of things is the so-called "superquadra" -- a manipulation of the vertical housing slab popularized by Swiss architect Le Corbusier and his protégés. In Brasilia, each super quadra -- and there are hundreds of them -- are almost identical: they are groupings of six 6-story residential buildings with ground floors that are public and open-air. Each super quadra is surrounded by local retail and thriving public spaces. As a model for mixed-use dense housing I found it quite successful as something between dense urban living and suburbia.

Modernity vs. Globalization

Contrast Brasilia with City of God, the Rio de Janeiro favela (slum) made famous by a movie of the same name. President Obama visited this area several days ago and championed the efforts at attaining citizen security in informal urban areas like this throughout Latin America. The president is right to highlight the joint economic terms by which the U.S. and Brazil can benefit. He is right to look for a silver lining to North America's economic troubles in Brazil and Chile's stellar economic growth.

But what is most interesting to witness is the tension between modernity and globalization -- the shift from making cities (like Brasilia) that depict hopeful conditions of future occupation to the more difficult project of reworking informal urbanism (like the City of God favela) that results from benign neglect and marginalization of a disproportionate number of black Brazilians who populate the country's favelas. That tension manifests itself in the realization that industrial modernization doesn't deliver economic equality or equality of opportunity, thus the naïve optimism of modernism has faded. Globalization, where we are today, allows more informed decisions about participation in world trade systems, but also allows Brazil's leaders to face squarely the system that has created a wealth class and, well, everyone else. They are building the middle class almost from scratch. In the U. S. we need to realize that where they are is where we are headed if we can't solve the twin crisis of a declining middle class and a voracious appetite for more personal space and the affinities for conventional suburban environments.

Symbolic architecture -- like Brasilia and the super quadra State-supported housing system -- can play a decisive role in both mobilizing the public's imagination and solving real social problems. Brazil will likely be bringing millions of its citizens out of poverty in the next 10-20 years; the U.S. will likely sink its middle class in that time to marginal status. The key to both countries realizing economic growth and to their citizens achieving "substantial freedom" is a vast investment in housing and transport systems and infrastructure, but also an investment in the aesthetics of the projects themselves. Architecture and urbanism can be used as a corrective measure to readjust national and civic priorities. If we want to shift the way in which citizens see themselves in the public sphere, then we are going to have to change the look and feel of the public sphere.

President Obama's initiatives for Race to the Top in education, a green economy and a renewed commitment to improving the national transportation infrastructure are all the right moves. What we need now is what President Kubichek produced in the 1950s -- a symbolic architectural/urban concept that mobilizes the nation to want to achieve its goals. President Jefferson did this with his plan for the nation's capital. The problem is that we don't build new cities like the Chinese or the Koreans, instead we are left with the vestiges of our legacy cities and metropolitan areas. What if we linked the infrastructure work with the green economy initiatives with the need to build mass housing to replace single-family housing -- so that we began to think about the singular systems of a city as an integrated organism. If we created pilot projects in the country's most deserted suburbs or depopulated cities maybe we could mobilize our public's imagination, prior to mobilizing the political and economic will to actually build some of these creations?

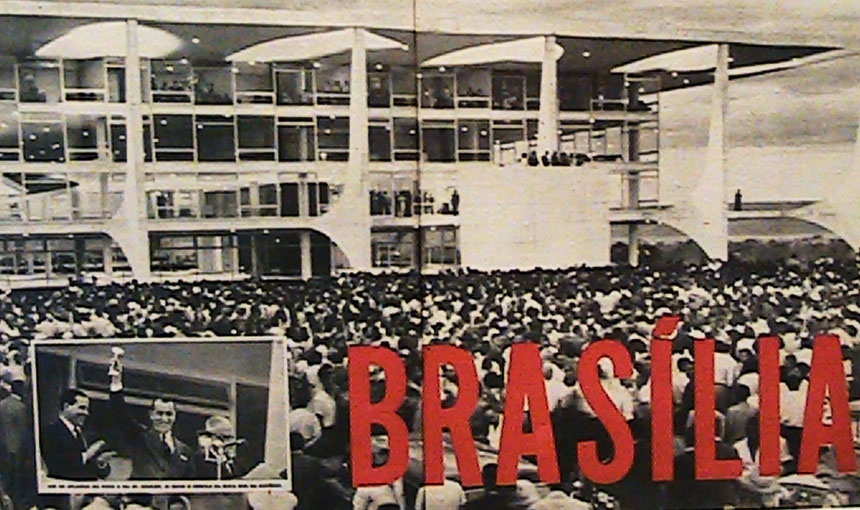

Images are all from Milton Curry, 2010: 1) news photo from Brasilia Exhibition,

2) Brasilia urban plan, 3) Brasilia Congress Halls and Office Tower, 4/5) Brasilia SuperQuadra Housing Towers