This is the first of a series of blog posts from me this summer about The Odyssey Project. I also wrote one last summer here.

I'm sitting in an office with an African-American man, a Native American woman, and a Latino youth. The youth's arms are covered in tattoos.

"Are you close with your family?" Michael Morgan, who is a UCSB voice professor from Harlem, asks the young man in his characteristically gentle voice.

"Yeah, my mom." The young man, whom I'll call Carlos*, ducks his head.

"What does your mom do for work?" Michael continues.

"She picks strawberries. From six in the morning to six at night. Then she works in the freezers."

"A triple shift every day?" Raven, the Native American counselor, shakes her head. "That is back-breaking work."

Carlos nods, glancing up at the monitor in the corner; on it we can see what the other boys are doing in the large dorm beyond the door.

"Is your dad on the scene?" Michael presses.

"Nah." Carlos looks at his feet. "Not since I was a baby."

"I see. Do you like to dance, or draw, or rap?"

Carlos smiles shyly. "I like to rap. And I like drawing. Dancing...I dunno."

"Would you be willing to try?" asks Michael. "Because in the Odyssey show we'll do, there's dancing. We use your raps, and your drawings, and you'll act and dance. You'll design a T-shirt and make a mask. Together with the others, you'll tell the epic story of Odysseus, and you'll be the heroes and the stars of the show. I'm a voice teacher. It's my job to help you find your center and what it's your destiny to say."

Carlos's shy smile widens. He's nodding.

Michael laughs. "But there's dancing, so..."

"Yeah, I'll try," Carlos says quickly.

There's a pause. Outside the dry, warm breeze shuffles the oak branches.

"Are you affiliated with a gang?" asks Raven.

"Um, yeah," comes the reluctant reply.

"Do you mind if I ask which one?" asks Raven.

"I don't know if I should, you know?" Carlos shifts in his chair.

Raven lets the matter drop. "Listen, honey," she says, touching Carlos's arm, "Because you're brown, you're just gonna be looked at differently. That's never gonna change, hon. And you're a few months from being eighteen, an adult. If you get out, and you get caught, and you're in adult jail, I can't help you anymore."

Michael speaks up. "We want to make sure you have support to create a different life for yourself when you finish camp, so that you don't end up being tried for something else as an adult. We're doing these interviews to get to know you a little better, and so you can ask us questions about the Odyssey Project and decide if it's something you're interested in. So..." He chuckles. "Is it something you're interested in?"

"Yes," says Carlos definitively.

The other seven boys say the same thing.

Incarcerated youth and UCSB undergraduates use their bodies onstage to form Odysseus's ship. (Photo credit: Clarissa Koenig)

At first, Paradise Road seems aptly named: it hairpins off of the San Marcos Pass near Santa Barbara, snaking through rolling hills pasteled with the muted colors of draught-ridden southern California, live oak trees bowing over the smoothly paved road from either side like a lover's lane. There's a state campground off this road, for good reason. This is the gorgeous land I grew up in, on a ranch about 30 miles north. I went to high school about fifteen miles away, at a ranch boarding school. This is a ranch boarding school too, of sorts. The scent of dry oatweed is sort of familiar to me, and the large-windowed cafeteria and the office and dorms seem familiar at first, too.

The difference is that the front gate of this place off Paradise has an intercom and a heavy gate. The difference is that instead of the bohemian tank tops and corduroy bell bottoms I wore to my school fifteen miles way as I picked lettuce in the garden for the school's lunch in the foggy valley mornings, the teenagers here all wear mandated converse sneakers, dark blue shirts, and grey shorts. The difference is that the adults employed here have security training and handcuffs on their belts. That the teenagers here are all male. That they are all convicted juvenile offenders (not for murder or rape; mostly for vandalism, theft, and possession of pot or cocaine). There are high school teachers here, and classrooms like the ones I got my college prep education in fifteen miles away. I too worked in the cafeteria like the lovely high-windowed room where I see a young guy hauling a tray of dishes, as I used to do. But here there are guards. They tell the "campers" to drop and do push-ups. They tell them to march.

And whereas when I got busted for smoking pot years ago in the neighboring town of Solvang, my public defender used my undergraduate institution to get me off easy. (My lack of an accent, my blonde hair, and my blue eyes almost certainly had something to do with it, too.) In short, the societal structures designed to let me off the hook when I screwed up, to forgive my mistakes and encourage me to excel, are the same ones designed to ensnare boys like Carlos and never let him go. It's a refrain among the boys: "Once in the system, always in the system."

The Odyssey Project, now in its fifth year, is using the arts to combat recidivism for juvenile offenders in a completely unprecedented way: by creating an arts-based "intervention" at that critical point near the end of a juvenile offender's teen years, when, like Odysseus, they have life choices to make that will indelibly determine their future's path.

To do so, the Project unites three very different arms -- a university, a municipality, and the juvenile justice system -- in a common goal: these young incarcerated men will co-star in the Odyssey Project's summer production on September 13th in downtown Santa Barbara. After a six-week summer workshop, which brings these young men to the UCSB campus to work alongside undergraduates, their hard work as a group culminates in this multimedia theater show about a flawed hero's epic journey home.

Over the course of the workshop, these young men (or "campers") -- who have often ended up friends through the workshop experience although they initially came from rival gangs -- have access alongside their UCSB undergraduate peers to twenty different university mentors and team members, from a mime expert to a dance choreographer to an LA-based rapper. They'll work throughout with Raven, a mentor/counselor who will continue meeting with them for months beyond the play's finish; ensuring consistent contact with family, prospective schools, and potential employers; and coaching them using Ruiz's "spiritual warrior" guidebook The Four Agreements as an anchor text.

The Odyssey Project has already won NEA support; now Michael, its founder, hopes to lead by example for juvenile detention programs around the country with a Kickstarter-driven documentary film. Last year I worked for the Project. This year I'm just observing, because I missed being in the room and listening to these young men and watching their faces as they scribbled in their journals, tried dance moves, and held up their drawings next to UCSB students. In the face of the relentless news cycle of young people of color oppressed, harmed, and killed by armed officials in this country seeming only to grow in the months since I worked for the Project -- and in the face of increasingly harrowing statistics about the school-to-prison pipeline in America -- the thing that gives me hope is knowing that the Odyssey Project continues, and that it might reach even more people through this documentary.

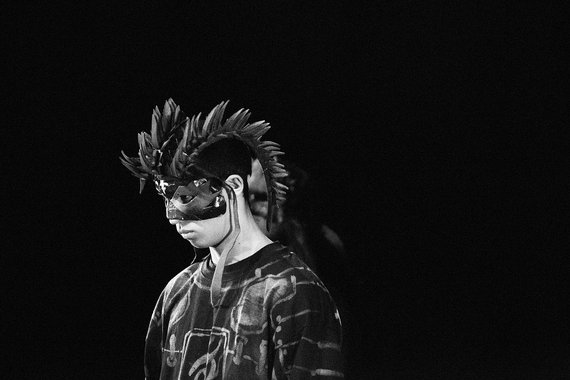

Today, the boys and the UCSB students began work on their masks, applying plaster strips to each other's faces as though they were brethren tending to each other after battle. The masks will be those of their "allies", the spirits who believe in the best of them and who, like Athena, defend their inherent goodness to the court of the gods.

The whole Odyssey class in 2014, performing a Chumash ceremony together at the beach near UCSB. (Photo credit: Clarissa Koenig)

The end of class approaches. "Any last questions?" Michael asks.

Carlos raises his hand. "Are we gonna do more yoga soon?" he asks.

Stay tuned for more dispatches from this summer's Odyssey workshop. Til then, check out the Kickstarter video for The Odyssey Project's documentary film.

*Names and identifying details have been changed. The youth in the photos have given permission for their photos to be used.