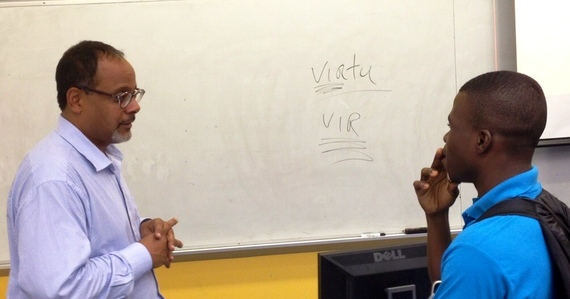

Last summer I organized a four-week summer institute in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The plan was to get 10 formerly incarcerated men and women into a college classroom to discuss character, agency and identity. One of the reasons for the program was that I believed that those incarcerated and formerly incarcerated have the potential to be some of the best philosophers, so why not spend my summer engaged in lively conversations with them? Moreover, I wanted to introduce them to a broad range of topics, as well as to other young philosophy professors of color -- while also hopefully using philosophy as a college pathway. Although my goals were pretty clear, I was concerned with how the process of discussing character with Black men and women, who had been through the penal system, could be misinterpreted as promoting a "politics of respectability."

It then dawned on me that "character talk" had in some ways become a bad word, tainted by the selfish and at times insensitive political goals of the elite. By "character talk," I am referring to discourse about being a good person -- what does it mean, what does it look like, how does one commence doing so and who decides what it means to be "good"? As a black female ethicist, who is very much intrigued with the nature of character and the possibilities of virtuous living as well as with issues concerning women and people of color, these questions are often very much in the forefront of my mind.

So, I found myself struck by the question: Is virtue, morality, or character talk synonymous with "respectability politics"? If not, how is it different? And how can we have meaningful "character talk" when including oppressed people and people of color as moral agents, as agents of change even, while evading the potential for the demeaning, pejorative conversations that respectability politics spews out.

Respectability Politics

During the Reconstruction era some Black Americans believed that the solution to social uplift was not in social reform but in individual moral behavior. Behind the idea was the concept that discrimination and systematic oppression took place because Whites did not respect Blacks. However, the theory went that if Blacks changed their behavior, fashion, and even music, Whites would begin to respect them and therefore treat them as deserving of dignity.

This ideology was described as a "politics of respectability" by Harvard Professor Evelyn Higginbotham in her book Righteous Discontent. Higginbotham argues that respectability politics began in the early 20th century with the women's movement in the Black Baptist church. These women saw respectability as political and used this discourse in their missionary, social and political work. According to Higginbotham, respectability politics allowed Blacks to "boldly assert their will and agency to define themselves," was a weapon against "social Darwinist explanations of blacks' biological inferiority to whites," and was a way to remove any excuse for segregation. For women, manners and morals where seen as protection against sexual insult and assault.

Higginbotham also claims that a politics of respectability reinforced stereotypical images of blacks, blamed them for their own discrimination, made black women fully accountable for the progress and downfall of the race, privatized racial discrimination, promoted a distancing of the "negative black other," became the defining factor of social status, and was always focused on the "white gaze."

Politics of respectability was also an ideology, targeted towards poor Blacks, urging them to get on board with behavior that Whites deemed respectable, as a necessary and sufficient condition of racial uplift. The Baptist women went door to door in urban poor cities with pamphlets promoting an ideology of moral and manners. W.E. B. Dubois' study "Efforts for Social Betterment" included one of their pamphlets on behavioral advice. The Chicago Defender posted weekly reminders targeting poor Black Chicago migrants, admonishing them against vulgar language and ragged clothes. Avoiding these things, the newspaper argues in a May 17, 1919 issue, "will disarm those who are endeavoring to discredit the race."

Today the politics of respectability is alive and well, whether passing through the lips of Bill Cosby, Stephen A. Smith, Bill O'Riley, Don Lemon or the practices of Black charter schools and historically Black colleges that ban Black students from wearing certain hairstyles. A politics of respectability is also present in our discourse about the mistreatment of women. We see it when it is suggested that if only "she did not wear that outfit," entice him, or incite him to anger, that woman would not have been raped or beaten.

The idea behind the respectability politics of our day is that in order to not be oppressed, discriminated against, victimized or treated harshly by others, it is the responsibility of the oppressed group to "act good." I do not agree with respectability politics. On the other hand, I love to talk about character. I think it is possible to talk about character and virtuous living without falling into a politics of respectability. A distinction between the two is necessary.

Character Talk vs. Politics of Respectability

There are differences between the character talk that ancient Greek philosophers, Aristotle and Plato, spoke about and the politics of respectability (disguised as character talk) that Cosby and Lemon opine about on cable television.

Character talk is not exclusively directed towards those living on the margins of society. On the other hand, a politics of respectability is always targeted towards oppressed groups. Plato argues that being just is a possibility for us all if only we allow our appetitive and spirited sides of ourselves get to under the control of reason. In other words, think with your head and not with your desires and urges.

Instead of moral excellence being a possibility for us all, politics of respectability places the burden of virtue on the oppressed and lets the oppressor off the hook. Instead of challenging the oppressor to be fair, loving, or unconditionally compassionate, they demand that the oppressed "pull up their pants," "don't wear hoodies," "remain chaste," and "don't be lazy" -- while simultaneously excusing the unethical acts of the oppressor towards them. Character talk does not encourage such moral laziness but rather demands moral accountability regardless of our social positions.

Character talk does not look to morality alone to solve our social problems. In Book One of Plato's Republic, Socrates meets Cephalus, a rich older man who admits that his wealth has made it possible for him to escape certain vices and as a result it has been easier for him to be virtuous. In addition, Aristotle admits that external goods such as friends and resources can help us to be more virtuous than if we did not have these things. While it is possible that bourgeois' comforts can induce their own vices, what's important to note here is that virtue is not seen as a solution to social problems rather social conditions are seen as a solution to acquiring certain virtues.

In other words, social conditions can help us become more virtuous but being morally virtuous does not equate to a change in social conditions. Instead of letting the oppressor off the hook, character talk has the potential of challenging the state and other institutions to improve social conditions so that lives can be improved morally.

A politics of respectability promotes an erroneous, contrast idea. It is erroneous because history has shown that 'acting better' does not bring about being 'treated better.' We must remember that four girls were in Sunday school when their Birmingham church was bombed. Amadou Diallo did not commit any crime, obeyed the police, but yet was shot 41 times by the police. We can count numerous times in which women were raped not because they wore short skirts or were intoxicated but simply because they were women. This is why in "A Case For Reparations", Ta-Nehisi Coates claims:

The kind of trenchant racism to which black people have persistently been subjected can never be defeated by making its victims more respectable. The essence of American racism [or any hatred for that matter] is disrespect.

Moreover, respectability politics is not a philosophy where we value morality for morality sake but it is used as a means to achieve respect from Whites and men: a goal that may never be achieved. I think the uniqueness of character talk is that it teaches us that morality's worth is not judged by how people respond to it, but it has value all by itself.

In the pursuit of social justice, a politics of respectability will fall short primarily because it's idea is for the disadvantaged to have certain virtues that are pre-approved by the oppressor. However, unjust conditions may lead people to possess the virtues of passion, anger, and irreverence as they pursue justice. While character talk can make room for these virtues, respectability politics will not tolerate them because these traits are threatening to the powers that be.

Moving Forward

Respectability politics may talk about character and morality, but it does it an injustice. A talk about character doesn't necessarily translate into a politics of respectability. We can aspire to moral excellence and challenge others to do so as well without singling out certain groups, by holding everyone accountable, by valuing goodness for goodness sake, and by knowing the limits of only morality to change the world.

These are the reasons I can now sit down with women, Latinos, Blacks, or poor students with a copy of Aristotle's Ethics in my hand and a clear conscious. I can do this because I know that talking about the moral potential of ourselves is not the same as selling ourselves out.