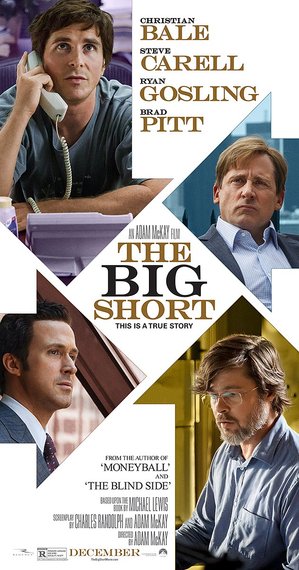

"The Big Short" is a fierce, funny, wildly entertaining and downright infuriating movie that tells the story of the 2008 subprime meltdown from the perspective of four men who saw it coming. They bought "short" (betting against Wall Street) and made fortunes. It is based on the book by Michael Lewis, who also wrote the books that inspired "Moneyball" and "The Blind Side." In an interview, Lewis talked about the qualities that made those four men see what no one else wanted to, and what he would do to make sure Wall Street could not melt down again.

How do you feel about making a lively but serious book about finance into a comedy?

I thought the one way to get people to watch this thing is to make them laugh first and then once you have made them laugh maybe you would have them hooked and you could teach them something.

Why were the men you wrote about the only ones who did not believe Wall Street's numbers? The numbers were endorsed by everyone including the presumably independent ratings agencies, the Federal Reserve, and the press.

In each case it was a bit different. In the case of Michael Burry who is played by Christian Bale, I think it was an immunity to information, to social information like propaganda from Wall Street. He has Asperger's syndrome; he doesn't like talking to people, he doesn't have really close friends, everything is numbers and analysis of numbers. And he persisted. And so as a result he didn't listen to anybody who said: "Oh, that triple-A is triple-A." He went and looked inside mortgage bonds to see what the mortgages actually were. I never really saw anybody else do that. So his approach got you the right answer which is: ignore what everybody else is saying and just look at the numbers, look at the data.

Second approach was the characters we call Charlie and Jamie, kind of the garage band hedge fund in the movie. They were just looking for out of the money bets. They were looking for long shot bets, out of the money options in any market. And they stumbled upon credit default swaps from subprime mortgage bonds. At first glance it was kind of a long shot bet. And then they started digging into it and they realize: my God, this is priced like a long shot but it is actually much more likely to happen than a long shot.

And then I would say the third approach that got you to the right answer was Steve Eisman, renamed Mark Baum in the movie, played by Steve Carell, and that was just a caustic cynicism about all things Wall Street and a previous experience with subprime mortgages in their first incarnation in the 90s. He had known that market when it had its first little bubblette and had seen corruption and fraud in it and so he was sort of waiting for the banks to do bad things again with them. So it took a kind of insistence and cynicism about the financial systems to pierce the armor of Wall Street.

It is also true that two of the men were in part cynical because they had experienced terrible tragedy. The Baum character -- in real life he lost a child and his wife said from that moment he actually believed really bad things can happen. It changed his own approach to how he went about life in the markets.

And in the case of Michael Burry, he told himself that the reason he had problems with people is that he lost an eye as a child and the glass eye was kind of weird and uncomfortable and off-putting and that turned out to be a false story. He had something else going on with him, it was undiagnosed but it is absolutely true that you can't separate their approaches in market from who they were as people and who they were as people from things that had happened to them.

There are different ways and different spirits in which you might operate and get to the right answer but all of them, the big point is the qualities in all of these people were absent at the heart of the financial system. People like this were not in Wall Street banks.

The most telling line in your book is the most outrageous. While the heroes of your book made enormous amounts of money, you wrote: "What's strange and complicated about it, however, is that pretty much all the important people on both sides of the gamble left the table rich." So it would be like having your "Moneyball" hero Billy Beane win the world series with his Oakland A's and somehow have the old-school New York Yankees win, too.

These banks were all, well almost all, on the wrong side of the bet and these weird outsiders were on the right side of the bet. Individuals, and yes, the banks took huge hits as a result of their stupidity but the people who made the bad bets all got rich and inside the banks they all got bonus after bonus as they were building up the debt and walked away with their money. And you realize that there was no incentive in the system to actually get the right answer. People were paying you some of the money to be wrong. When people are paying them tons of money to be wrong, they will be.

It is also true that when you look at the system now and you want to ask questions to which there is now a massively complicated answer: "What has been done to fix the problem?" the real way to ask the question is: "What has been done to fix the incentives?" Like how are the incentives in the system changed? It is shockingly little. Compensation practices have changed a bit so you don't get all your money in cash at the end of the year if you are a trader and the risk-taking inside the Wall Street firm has changed at least a bit, maybe more than a bit. There has been some change but the reform movement didn't attack the incentive problem directly.

So if you could make a change now, what would it be?

The first thing I would do is break up the banks so that they are much smaller and they could all fail. They would be subjected to honest market forces because you've got these essentially socialist enterprises in the capitalist system and inside the socialist enterprises are the most highly paid people in the society, which is crazy. That is probably the first thing I would do but there is a long list. I mean the ratings agencies are still paid by the issuers to rate the security. That's crazy. And the buyers are required to use their ratings so that's crazy.

We saw where it led. Now what happens is we delude ourselves into thinking that the vigilance we all feel and see on the backend of a global crisis will prevent it from happening again, that people are watching now. And it may take a while before the incentives corrupt the system again but having not changed the incentives you really can't expect to have changed the behavior and so the behavior is going to come back.

In addition to breaking up the banks, I would say if you're going to have these institutions that are making big bets, they shouldn't be public companies, they should be partnerships. Shareholders are very bad at monitoring the risks these institutions are taking and partnerships are proven very good at it because the partners are on the scene and they lose everything if things go bad. So I would just go in and rearrange things so that the incentives were right for everybody, so everybody was much more incentivized with a view for the long-term, to getting rich very slowly and over a long life in finance rather than immediately.

Right now these risk-taking enterprises are too big to manage. When I was in Salomon Brothers, it was like 8000 or 9000 employees and the products were complicated but much less complicated than they are now. And you could see that whoever the CEO was would never have any ability to monitor these very clever employees strung across the globe. It was just too complicated already and now they are massively bigger and more complicated. There is no way one person could properly manage these companies. They don't know what is going on in their own shops. And we can't wait around for the next Michael Burry to figure it out.