We've all had the experience of thinking we can predict the limits of someone's achievement. Most of the time, the surprises we do get from friends and family still fall within certain parameters. We are fairly sure we can guestimate how far or fast Trevor can run if he pushes himself, or how Richard can make an osso bucco up there among the tastiest if he just takes the time. But with artists and writers we know who work amongst us but see only at social occasions, the proof is more elusive: the pudding can be either a treacly jelly that never quite sets up or a perfect cake layering through the world. And then one always fears the moment when the creation is finally unveiled--how will we react?

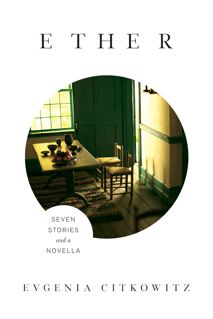

It's a happy occasion then--and somewhat of a revelation--to find that the work that my friend Evgenia Citkowitz has been quietly and privately doing turns out to be truly accomplished. Her new book, her very first, a collection of short stories called Ether has just been published and I have taken the unusual step of breaking my own rule to never write about the work of friends to tell you a little about Evgenia, and then let you hear from her directly about some of things that have informed the work. Though her short stories have been published in various British magazines and her screenplay The House in Paris, based on Elizabeth Bowen's novel, is currently in development, I think it is the start of a brilliant career and short stories, like small, independent films, often need a boost to get noticed.

It's a happy occasion then--and somewhat of a revelation--to find that the work that my friend Evgenia Citkowitz has been quietly and privately doing turns out to be truly accomplished. Her new book, her very first, a collection of short stories called Ether has just been published and I have taken the unusual step of breaking my own rule to never write about the work of friends to tell you a little about Evgenia, and then let you hear from her directly about some of things that have informed the work. Though her short stories have been published in various British magazines and her screenplay The House in Paris, based on Elizabeth Bowen's novel, is currently in development, I think it is the start of a brilliant career and short stories, like small, independent films, often need a boost to get noticed.

Image (C) Suzanne Tenner.

Evgenia was born in New York and was educated in London and the United States. She comes from a rather storied family. Her mother, beautiful and large-living English muse and writer Lady Caroline Blackwood was our poet laureate Robert Lowell's wife, notorious for having captured him away from the brilliant American writer Elizabeth Hardwick. Evgenia's own father Israel Citkowitz was a composer. Blackwood's first husband was the painter Lucien Freud. Evgenia grew up both amongst these strong personalities and at a certain remove: she went away to school and then finally moved to Los Angeles, a place her mother had once lived, but had not had a chance to dominate the way she did in the literary worlds of London and New York.

Evgenia has made a point of keeping these luminaries at bay. (In the coming years, other members of her extended family and a new biographer will attempt to dissect this hothouse world more pointedly for American readers.) Yet her clear-eyed, sharp witted, often surprising view of the world cannot have been entirely uninformed by this celestial orbit. Even so, her take on the world is wholly original. She is a wit and a seer, setting seemingly everyday folk in unusual circumstances and then showing us that normal doesn't really exist, after all, and that unreliable narrators can lurk everywhere. There is something for everyone in this collection: mothers tangling with the needs of their daughters, furniture movers who understand the power of a hidden stack of letters, nannies who see into the lives of the rich and powerful, and the care, and then spoils, of a high profile marriage.

Evgenia has made a point of keeping these luminaries at bay. (In the coming years, other members of her extended family and a new biographer will attempt to dissect this hothouse world more pointedly for American readers.) Yet her clear-eyed, sharp witted, often surprising view of the world cannot have been entirely uninformed by this celestial orbit. Even so, her take on the world is wholly original. She is a wit and a seer, setting seemingly everyday folk in unusual circumstances and then showing us that normal doesn't really exist, after all, and that unreliable narrators can lurk everywhere. There is something for everyone in this collection: mothers tangling with the needs of their daughters, furniture movers who understand the power of a hidden stack of letters, nannies who see into the lives of the rich and powerful, and the care, and then spoils, of a high profile marriage.

CZ: You have an unusual background. You spring from British nobility, both social and literary, yet you seem to have found a way to separate yourself from what clearly could be both a blessing and a curse. How did you manage?

EC: I would qualify your description about coming from British nobility. My father was a Polish immigrant. He arrived in New York as a child with his family and little money. His parents sold yarn. My mother was Northern Irish. That's different from being "British." It's a very different emotional climate there. She wasn't grand. She was bohemian. We didn't have white-gloved retainers to run our lives but hippie nannies and a filthy Volvo. We lived in large houses but they were always shambolic. We were privileged but not spoiled. I suppose the most conventional family member was my maternal grandmother whom we didn't see much growing up. But as every generation separates from the next, I have tried to shape my life according to my values and the way I want to live. I feel at home in America because I always felt like an outsider in England. Now I'm just another Californian minority, and I'm very comfortable with that. As to literary nobility, that makes everyone seem rather exalted when it was a just a community of writers - granted, talented ones - who drank and smoked too much, but as a compliment to Caroline and the wonderful writer she was, it's good of you to recognize that.

CZ: You have made your home in Los Angeles, very far from the epicenter of the particularly incestuous literary world that your mother, Caroline Blackwood, at one time dominated. Was this a conscious choice?

EC: Yes and no. There was an element of journeying to find a niche, a place where one could fit in, and that involved leaving people and places behind, consciously and unconsciously. Things happen as a series of small decisions, and often it's only in hindsight that one realizes one has taken a position. But yes, it's a conscious choice to live here, as opposed to, say, Alaska.

CZ: You have written screenplays and your husband Julian Sands is an actor. At one time, your mother did spend some time in Los Angeles. Your novella is largely set in Los Angeles. How does Hollywood inform your work?

EC: It's true that I draw on, take inspiration from surrounding geography. It can be subtle, a shard that suggests an idea that metamorphoses into something else, and not so subtle as in the case of Ether where Los Angeles is clearly the backdrop for several of my characters. Right now I'm trying to write a story to include a California Quail because I keep seeing them in the morning and they are baroque and somehow comical, but let's just say, it isn't flowing. I'm less interested in the Hollywood comprised of the movie business and the cult of celebrity - in any case global and now extends way beyond LA - than how it affects the inner lives of the people who inhabit that world, especially those on the fringe. CZ: Motherhood creeps into many of your stories. You are the mother of two young children. How does this responsibility inhibit or enhance your ability to write and see your own past in another light?

EC: Having children has made me more disciplined. I have a window of opportunity in which to write. I have to flow with the ebb and tide of the school term. I have short days and long ones - sometimes no days - but that's okay because my children are the priority. Motherhood is an expansion of the heart and mind and my greatest joy. It's hard for me to be objective and say how it has affected my writing. It has certainly made me more flexible, which is good. When you become a mother, intentions about parenting are immediately contrasted with childhood experiences, inviting comparisons, not always favorable. Each generation rewrites the next. It's a prerogative. When I look back on my chaotic childhood, it's with some alarm but a great deal of affection. Should my mother have done things differently? Yes. And yet, that was our experience, and it's not for me to deny all her choices. That's too easy. My life is all the more complex and interesting for it.

CZ: The unexpected toxicity of people whether they be nannies, mothers or hamster-sitters is a theme running through your work. It seems betrayals, both small and large, can lurk everywhere. Is this a jaundiced or clear eyed view and is it particular to a rarefied world?

EC: I'm going to quote Jodi Picoult here, or at least I think I'm quoting her, anyway someone said that to write about dark subjects is to ward them off in some way. I think that's how I deal with my fears. There's darkness in the world. You'd have to be blind not to see it. But that doesn't mean to say that I don't believe that people have the capacity for extraordinary goodness. They do. I'm a humanist at heart. The people in my stories have become toxic because of something that happened to them. They're damaged, not evil. I'd like to think I have compassion for them. I'm hoping the reader will too. I'm thinking I will lighten up for my next book...

Evgenia Citkowitz is having a dialog Thursday night with actor and director Michael Lindsay-Hogg at 192 Books in New York at 7 pm and then in Los Angeles and Seattle and other cities in the coming weeks.