Co-authored with Lance J. Sussman, Ph. D., Senior Rabbi at Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel and member of the Executive Board of the American Jewish Archives.

Jewish faith and Jewish culture are intimately tied to the past. Deuteronomy 32:7 reminds us to "remember the days of old" while Job 8:8 admonishes us to "ask former generations and seek out what their ancestors learned."

But how do we learn from former generations and how to do we teach the next generation of Jewish Americans to appreciate their collective past? One answer is the creation of synagogue-based Digital Jewish Archives. We live in a digital age. Baby Boomers are increasingly online. Gen-Xers and millennials turn to the internet for almost all of their information. Synagogues, cemetery associations, and other communal organizations must post their archives on the web if they are to meet the intellectual and personal needs of today's Jewish community.

Currently, most synagogues only use the internet as a simple tool for informing existing members of congregational news and events and recruiting new members. But such a perspective misses two major points. First, digital archives can be used as an important educational tool for existing members -- especially younger members. Second, through online synagogue archives unaffiliated Jews or new members feel personally connected and rooted to their heritage as they learn about the past. This in turn helps them engage with the synagogue and other community institutions.

Most people, sooner or later, seek to better understand their family heritage and their cultural past. The incredible commercial success of Ancestry.com illustrates the growing interest in family history, genealogy, and shared cultural experiences. When millennials decide to learn about their family and collective past -- as they almost certainly will -- they will turn to the Internet. Synagogues need to have their archives up and running when this happens.

Synagogue archives are complex. They are filled with fascinating information, compelling documents, pictures, video files, and audio records. Minutes of board meetings reveal the internal history of an institution, but also show how communities responded to outside events and the larger political world. Like most institutions synagogues also keep important legal, business, and financial records which must be preserved. These might include old contracts with former rabbis, records of donations and investments, and even old building and renovation plans. These synagogue archives tell a piece of the story of American Judaism.

But beyond the business records, synagogue archives provide a wealth of knowledge about how American Judaism evolved. There are marriage records, birth records, death and burial records. We have thousands of unpublished confirmation class pictures as well as pictures from religious schools. We have the correspondence, and often the photographs, of congregational leaders and the records of internal debates over synagogue policy. We have huge numbers of photographs, audio recordings, and even old home movies of events and people. We have rabbinic writings and sermons on theological, ethical, communal, and even political issues.

The archives remind us that what we think is a new problem, may not be new at all. For example, Reform Jews have been debating the issue of intermarriage for more than a century, with distinguished rabbis offering conflicting opinions. We have had internal debates over who is a Jew for membership purposes, what constitutes proper adherence to dietary laws, and whether to have mixed seating in synagogues.

Especially on the American frontier -- and we need to remember that all America was a frontier at one point -- there were perennial questions about how to maintain Jewish culture and identity, and who indeed was a Jew in a world where there were not yet existing communities. Such issues were debated in synagogues and those debates can best be traced in archival materials. Here is one striking example of such an issue. The remains of the famous western lawman, Wyatt Earp, are buried in a Jewish Cemetery next to his common law wife, Josephine Sarah "Sadie" Marcus Earp. Did the trustees of Hills of Eternity Memorial Park in Colma, California debate whether to allow the ashes of the famous, but clearly non-Jewish, Marshal Earp to be buried there? Were they concerned about his faith or that the cemetery was receiving his ashes and not his body? If the records of the cemetery association were online we could "see beyond the grave" of this famous man and countless others who helped shape American Jewish culture.

Synagogue records include the correspondence of rabbis, congregational presidents, and other figures. These records reveal debates and discussions over how those who came before us responded to current events such as pogroms in Europe, Henry Ford's anti-Semitic diatribes, Father Coughlin's hateful radio programs, the place of Zionism in American Jewish life, and the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust.

Since World War II, many American Jews have settled in suburban communities which often lack a Jewish demographic center. Synagogues have become those "centers" and the synagogue archives are the records of the social history of late twentieth century American Judaism. Synagogue archives help us understand the perennial debates among American Jews over the best ways to build and sustain communities. To understand the past of American Judaism and secure its future we must preserve and digitize these archives and make them accessible via the internet.

Archives provide a key to our past. We know that "the past is prologue." What came before us helps explain who we are and also helps guide us into the future. But synagogue archives also provide the tools for inspiring members of the next generation. Young members can become deeply engaged in Judaism through what is essentially local history. Millennials and Gen-Xers can feel a sense of being rooted in their community and the communities of their ancestors by simply going online. While many Millennials reflexively see "history" as a boring collection of dates and facts, they are also enthralled by personal connections to the past through documents, records of their own families, archival pictures, or just "cool" old stuff. Using digital archives can help Millennials or older congregants find family members. The archives will lead users to interesting people involved in Jewish life and in the Jewish life of the community where they live. Access to archives and records can inspire users and even give them a sense of pride and connection to those who came before them. Digital archives can help younger congregants, even very young students, to follow Job's advice to "ask former generations and seek out what their ancestors learned." The digital archives can provide continuity as people connect with their collective past. Importantly, young people get everything online today; if we want them to connect to their past and to our collective Jewish history, we must provide them with an online avenue.

Older synagogues obviously have some advantages here, but even newer ones have a history. The authors of this article are part of a project to digitize the records of Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel (known as KI), which was established in 1847. KI is the fourth-oldest continuous congregation in Greater Philadelphia as well as one of the oldest Reform congregations in America.

Soon KI's students will be searching for KI Civil War soldiers, such as Private Isaac Snellenburg, who died in combat in 1862, at age 16, or Col. Max Einstein, who fought at the first battle of Bull Run and whose funeral was at KI in 1906:

All images are from the archives of Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel, Elkins Park, Pa., and are used here with permission.

They will look at records and pictures of members who served their country in subsequent wars, including Rabbi Joseph Krauskopf, who led services for Jewish members of Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders in Cuba in 1898. They will also learn about KI members who held public office including state and federal judges. They will search out leading businessmen, entertainment figures, and even the occasional criminal. They will learn about the rise of women in a previously all-male hierarchy as teachers, lay leaders, synagogue presidents, cantors, and rabbis. They will learn of famous members who shaped our nation and the world, such as the founders of CBS, Sears and Roebuck, and the Guggenheim Foundation.

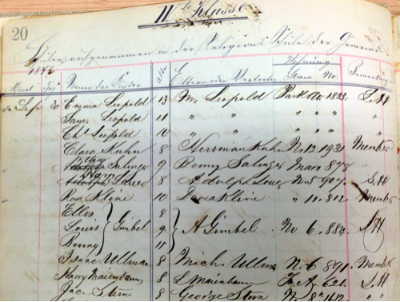

They will see the KI religious school roster with the three Gimbel brothers, who would later be the founders of Gimbel's Department Stores:

They will read about KI's most famous honorary member, Albert Einstein, who agreed to associate with the synagogue in 1934:

The purpose of these archives is not only to inspire with big names but also to give the next generation, as well as many adult members, a true sense of how their synagogue arrived at where it is today. Other synagogues, throughout the nation, can do similar projects with their archival records.

Digitizing archives makes these stories accessible -- and it also preserves them. Many synagogues do not have acid free archive boxes to preserve their archives. Nor do they have fireproof rooms to store their records. Jews know all too well the tragedy of records destroyed in burning buildings. You cannot burn down a website stored in the cloud. Some synagogues lack the resources or space for long term storage of old records. But scanning is relatively inexpensive, requires no great commitment of space, and ensures preservation of crumbling newspapers and poorly preserved documents.

We, of course, advocate the preservation of original documents and archives. As professional historians, we know that for some types of research, the actual document is essential. We also advocate using archival materials for public displays -- to educate congregants and others about the synagogue's past. We also want to use original documents to teach students -- and members of adult education programs -- about the synagogue and its past. There is something truly magical about holding the record book of marriages from the nineteenth century that might include your ancestors or those of your friends. But, the future of preservation involves scanning these documents, putting them online, and making them available to professional scholars and amateur researchers everywhere, as well as to members of our own communities.

These projects will allow both the scholarly world, and the rapidly growing interest of the general public, to access and use American Jewish historical sources. More extensive and creative use of archives will bring adult members of our community back to the synagogue as they search for their family's history. These records will also tie geographically disparate communities. At KI, there are marriage records from the 1860s showing KI members forming family unions with Jews from St. Louis or Memphis. Shared records can connect communities. They can help us identify the birthplaces here and abroad of our ancestors.

We believe that Jewish organizations should put their own archives online and work collectively to create a national (and someday international) website for synagogue and other Jewish community archives. Once online, they can be used everywhere and by everyone and help Jewish communities grow in the future. These communities will then more easily "remember the days of old" and be able to "ask former generations and seek out what their ancestors learned."